SpaceX

SpaceX & ULA could compete to launch NASA’s Orion spacecraft around the Moon

In barely 48 hours, the future of NASA’s SLS rocket was buffeted relentlessly by a combination of new priorities in the White House’s FY2020 budget request and statements made before Congress by NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine. Contracted by NASA to companies like Boeing, the outright failure of SLS contractors to stem years of launch delays and billions in cost overruns has lead to what can only be described as a possible tipping point, one that could benefit companies like ULA, SpaceX, and Blue Origin.

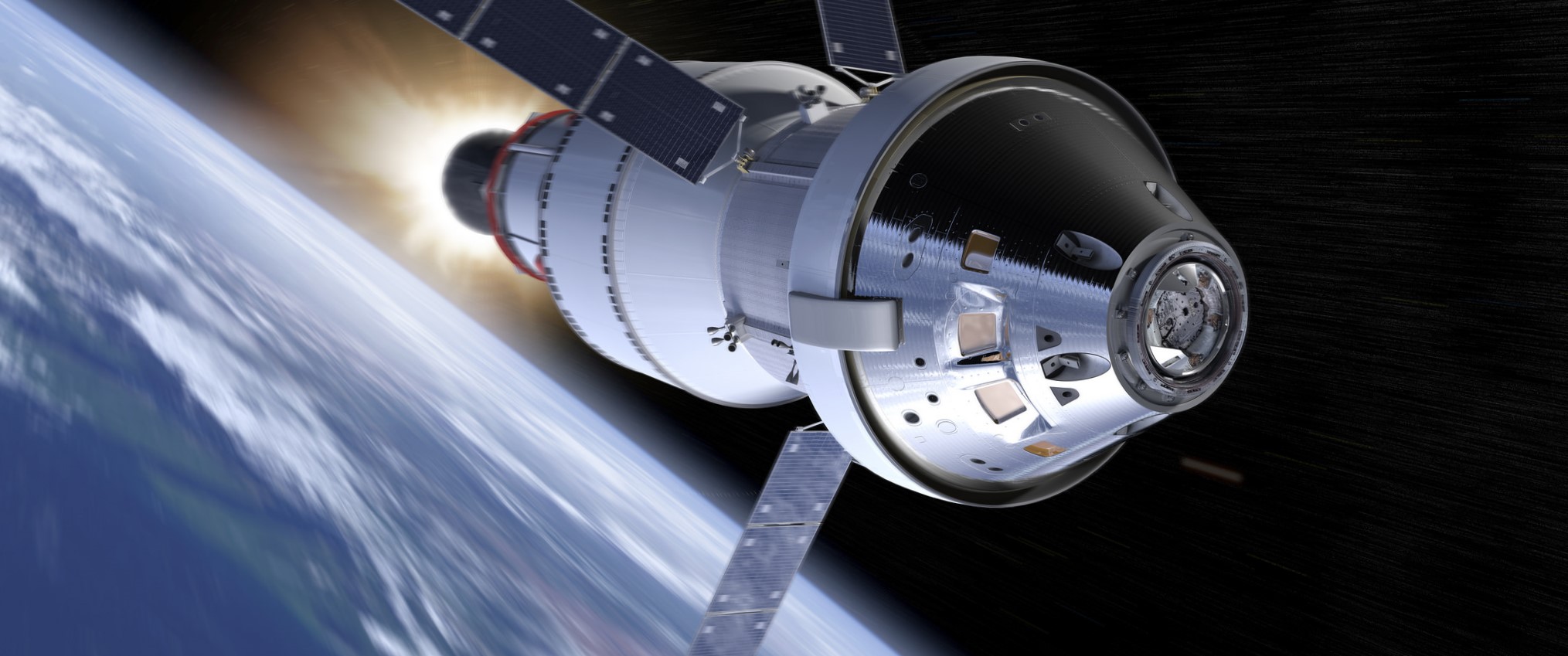

On March 11th, the White House’s 2020 NASA budget request proposed an aggressive curtail of mission options available for the SLS rocket, preferring instead to save hundreds of millions (and eventually billions) of dollars by prioritizing commercial launch vehicles and indefinitely pausing all upgrade work on SLS. On March 13th, Administrator Bridenstine stated before Congress that he was dead-set on ensuring that NASA sticks to a current 2020 deadline for Orion’s first uncrewed circumlunar voyage (EM-1), even if it required using two commercial rockets (either Falcon Heavy or Delta IV Heavy) to send the spacecraft around the Moon next year. In both cases, it’s safe to say that the political tides have somehow undergone a spectacular 180-degree shift in attitude toward SLS, the first salvo in what is guaranteed to be a major political battle.

“Deferred” upgrades

Of the many potential challenges the ides of March have placed before SLS, the first and potentially most significant involves the rocket’s tentative path to future upgrades over the course of its operation. Those upgrades primarily center around the Exploration Upper Stage (EUS) and a new mobile launcher (ML) platform, as well as a longer-term vision known as SLS Block 2. At least with respect to the EUS, NASA (and politicians) were apparently less and less okay with the extraordinary amount of money and time Boeing suggested it would need to develop the new upper stage, to the extent that cutting (or “deferring”) its development could likely save NASA billions of dollars between now and the distant and unstable completion date. Without the EUS, SLS would be dramatically less useful for extreme deep space exploration, effectively the entire purpose of its existence. Instead, the White House included language that would limit SLS launches to crew transfer missions with the Orion spacecraft and nothing more, cutting out heavy cargo missions for science or station-building. Ultimately, those crew transport launches would probably be more than enough to keep SLS Block 1 and Orion busy.

However, two days later, Administrator Bridenstine stated before Congress that he was dead-set on ensuring that NASA sticks to a current 2020 deadline for Orion’s first uncrewed circumlunar voyage (EM-1), going so far as to suggest that NASA was examining the possibility of launching the ~26 ton (57,000 lb) spacecraft on a commercial rocket, followed by a separate launch of a boost stage to send Orion to the Moon. If this were to occur, the consequences could be far-reaching for SLS, potentially delaying the first crewed launch of Orion on SLS until EM-3 and creating a ready-made, one-to-one replacement for SLS at drastically lower costs. At that point, nothing short of political heroics and aggressive bribery could save the SLS program from outright cancellation.

As it stands, the only rockets capable of conceivably supporting a 2020 launch of the 26-ton Orion are ULA’s Delta IV Heavy and SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy, both of which are certified by NASA for (uncrewed) launches. In fact, Falcon 9 was very recently certified by NASA’s Launch Services Program (LSP) to launch the highest priority NASA payloads, signifying the space agency’s growing confidence in SpaceX’s reliability and mission assurance. While the process of certifying Falcon Heavy for an uncrewed Orion launch would be far more complicated than simply grouping Falcon 9’s readiness with Heavy, it would no doubt help that Falcon Heavy is based on hardware (aside from the center core) almost identical to that found on Falcon 9.

The fact that Bridenstine indicated that the primary goal of these potential changes was to speed up EM-1 – an uncrewed demonstrated of Orion functionally similar to Crew Dragon’s recent DM-1 mission – is also significant, as is the fact that such a commercial SLS stand-in would require two separate launches to complete the mission. One launch would place Orion and its service module (ESM) into Low Earth Orbit (LEO), while a second launch would place a partially or fully-fueled upper stage into orbit to propel Orion on a trajectory that would take it around the Moon and back to Earth, similar to the milestone Apollo 8 mission. The need for two launches and the fact that Orion would be uncrewed means that both SpaceX and ULA would be possible candidates for either or both launches, potentially allowing NASA to exploit a competitive procurement process that could lower costs further still.

If Europa Clipper is anything to go off of, launching Orion EM-1 on a commercial rocket could save NASA and the US taxpayer at least $700M (before any potential development costs), aided further by potential competition between ULA and SpaceX. On the other hand, a system that can launch Orion and support EM-1 could fundamentally support all Orion EM missions, of which many are planned. Whether or not Bridenstine and the White House have considered the ramifications, what that translates into is a direct and pressing threat to the continued existence of SLS, with the White House recommending that the rocket be barred from launching large science missions or space station segments as the NASA administrator proposes making it redundant for Orion launches. As Ars Technica’s Eric Berger rightly notes in the tweet at the top of this article, those are the only three conceivable projects where SLS would have any value at all.

If NASA actually went through with this preliminary plan to launch Orion around the Moon on a commercial rocket, they agency would have also fundamentally created a packaged replacement for SLS with a price tag likely 2-5 times cheaper. If Congress had the option to choose between two offerings with similar end-results where one of the two could save the US hundreds of millions of dollars at minimum, it would be almost impossible to argue for the more expensive solution.

Battle of the Heavies

Despite the potential competitive procurement opportunity for a commercial Orion launch, things could get significantly more complicated depending on the political motivations behind the White House and NASA administrator. While Bridenstine explicitly avoided saying as much, the options available to NASA would be ULA’s Boeing-built Delta IV Heavy (DIVH) rocket and SpaceX’s brand new Falcon Heavy. DIVH holds a present-day advantage with active NASA LSP certification for uncrewed spacecraft launches, something Falcon Heavy has yet to achieve.

Nevertheless, it could be the case that NASA, Bridenstine, and/or the White House have a vested interested in potentially replacing SLS for crewed Orion launches entirely. Either way, it’s incredibly unlikely that NASA would launch SLS for the first time ever with astronauts aboard, a massive risk that would also patently contradict the agency’s posture on Commercial Crew launch safety, which has resulted in one uncrewed demo for both Boeing and SpaceX before either be allowed to launch astronauts. NASA also demanded that SpaceX launch Falcon 9 Block 5 seven times in the same configuration meant to launch crew. If NASA is actually interested in at least preserving the option for future crewed launches using the same commercial arrangement, Falcon Heavy is by far the most plausible option Orion’s first uncrewed launch. NASA and SpaceX are deep into the process of human-rating Falcon 9 for imminent Crew Dragon launches with NASA astronauts aboard, meaning that NASA’s human spaceflight certification engineers are about as intimately familiar with Falcon 9 as they possibly can be.

Given that much of Falcon Heavy has direct heritage to Falcon 9, particularly so for the family’s newest Block 5 variant, SpaceX has a huge leg up over ULA’s Delta IV Heavy if it ever came time to certify either heavy-lift rocket for crewed launches. In a third-party study commissioned by NASA and completed in 2009, The Aerospace Corporation concluded that Delta IV Heavy could be human-rated but would require far-reaching modifications to almost every aspect of the rocket’s hardware and software. Most notably, Aerospace found – in a truly ironic twist of fate – that Boeing would likely need to develop a wholly new upper stage for a human-rated Delta IV Heavy, increasing redundancy by increasing the number of RL-10 engines from two to four. As proposed by Boeing, the Exploration Upper Stage – under threat of deferment due to high cost and slow progress – would also feature four RL-10 engines and much of the same upgrades Boeing would need to develop for EUS. Aside from an entirely new upper stage, ULA would also need to develop and qualify an entirely new variant of the RS-68A engine that powers each DIVH booster. Ultimately, TAC believed it would take “5.5 to 7 years” and major funding to human-rate Delta IV Heavy.

Meanwhile, Falcon Heavy already offers multiple-engine-out capabilities, uses the same M1D and MVac engines – as well as an entire upper stage – that are on a direct path to be human-rated later this year, and two side boosters with minimal changes from Falcon 9’s nearly human-rated booster. NASA would still need to analyze the center core variant and stage separation mechanisms, as well as Falcon Heavy as an integrated and distinct system, but the odds of needing major hardware changes would be far smaller than Delta IV Heavy.

Regardless, it will be truly fascinating to see how this wholly unexpected series of events ultimately plays out as Congress and its several SLS stakeholders begin to analyze the options at hand and (most likely) formulate a battle plan to combat the threats now facing the NASA rocket. According to Administrator Bridenstine, NASA will have come to a final decision on how to proceed with Orion EM-1 as soon as a few weeks from now.

Check out Teslarati’s Marketplace! We offer Tesla accessories, including for the Tesla Cybertruck and Tesla Model 3.

Elon Musk

Musk bankers looking to trim xAI debt after SpaceX merger: report

xAI has built up $18 billion in debt over the past few years, with some of this being attributed to the purchase of social media platform Twitter (now X) and the creation of the AI development company. A new financing deal would help trim some of the financial burden that is currently present ahead of the plan to take SpaceX public sometime this year.

Elon Musk’s bankers are looking to trim the debt that xAI has taken on over the past few years, following the company’s merger with SpaceX, a new report from Bloomberg says.

xAI has built up $18 billion in debt over the past few years, with some of this being attributed to the purchase of social media platform Twitter (now X) and the creation of the AI development company. Bankers are trying to create some kind of financing plan that would trim “some of the heavy interest costs” that come with the debt.

The financing deal would help trim some of the financial burden that is currently present ahead of the plan to take SpaceX public sometime this year. Musk has essentially confirmed that SpaceX would be heading toward an IPO last month.

The report indicates that Morgan Stanley is expected to take the leading role in any financing plan, citing people familiar with the matter. Morgan Stanley, along with Goldman Sachs, Bank of America, and JPMorgan Chase & Co., are all expected to be in the lineup of banks leading SpaceX’s potential IPO.

Since Musk acquired X, he has also had what Bloomberg says is a “mixed track record with debt markets.” Since purchasing X a few years ago with a $12.5 billion financing package, X pays “tens of millions in interest payments every month.”

That debt is held by Bank of America, Barclays, Mitsubishi, UFJ Financial, BNP Paribas SA, Mizuho, and Société Générale SA.

X merged with xAI last March, which brought the valuation to $45 billion, including the debt.

SpaceX announced the merger with xAI earlier this month, a major move in Musk’s plan to alleviate Earth of necessary data centers and replace them with orbital options that will be lower cost:

“In the long term, space-based AI is obviously the only way to scale. To harness even a millionth of our Sun’s energy would require over a million times more energy than our civilization currently uses! The only logical solution, therefore, is to transport these resource-intensive efforts to a location with vast power and space. I mean, space is called “space” for a reason.”

The merger has many advantages, but one of the most crucial is that it positions the now-merged companies to fund broader goals, fueled by revenue from the Starlink expansion, potential IPO, and AI-driven applications that could accelerate the development of lunar bases.

Elon Musk

SpaceX launches Crew-12 on Falcon 9, lands first booster at new LZ-40 pad

Beyond the crew launch, the mission also delivered a first for SpaceX’s Florida recovery operations.

SpaceX opened February 13 with a dual milestone at Cape Canaveral, featuring a successful Crew-12 astronaut launch to the International Space Station (ISS) and the first Falcon 9 booster landing at the company’s newly designated Landing Zone 40 (LZ-40).

A SpaceX Falcon 9 lifted off at 5:15 a.m. Eastern from Space Launch Complex 40 (SLC-40) at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, placing the Crew Dragon Freedom into orbit on the Crew-12 mission.

The spacecraft is carrying NASA astronauts Jessica Meir and Jack Hathaway, ESA astronaut Sophie Adenot, and Roscosmos cosmonaut Andrey Fedyaev, as noted in a report from Space News.

The flight marked NASA’s continued shift of Dragon crew operations to SLC-40. Historically, astronaut missions launched from Launch Complex 39A at Kennedy Space Center. NASA is moving Falcon 9 crew and cargo launches at SLC-40 to reserve 39A for Falcon Heavy missions and future Starship flights.

Crew-12 is scheduled to dock with the ISS on Feb. 14 and will remain in orbit for approximately eight months.

Beyond the crew launch, the mission also delivered a first for SpaceX’s Florida recovery operations. The Falcon 9 first stage returned to Earth and touched down at Landing Zone 40, a new pad built adjacent to SLC-40.

The site replaces Landing Zone 1, located several kilometers away, which has been reassigned by the U.S. Space Force to other launch providers. By bringing the landing area next to the launch complex, SpaceX is expected to reduce transport time and simplify processing between flights.

Bill Gerstenmaier, SpaceX’s vice president of build and flight reliability, stated that landing close to the pad keeps “launch and landing in the same general area,” improving efficiency. The company operates a similar side-by-side launch and landing configuration at Vandenberg Space Force Base in California.

Elon Musk

Starlink terminals smuggled into Iran amid protest crackdown: report

Roughly 6,000 units were delivered following January’s unrest.

The United States quietly moved thousands of Starlink terminals into Iran after authorities imposed internet shutdowns as part of its crackdown on protests, as per information shared by U.S. officials to The Wall Street Journal.

Roughly 6,000 units were delivered following January’s unrest, marking the first known instance of Washington directly supplying the satellite systems inside the country.

Iran’s government significantly restricted online access as demonstrations spread across the country earlier this year. In response, the U.S. purchased nearly 7,000 Starlink terminals in recent months, with most acquisitions occurring in January. Officials stated that funding was reallocated from other internet access initiatives to support the satellite deployment.

President Donald Trump was aware of the effort, though it remains unclear whether he personally authorized it. The White House has not issued a comment about the matter publicly.

Possession of a Starlink terminal is illegal under Iranian law and can result in significant prison time. Despite this, the WSJ estimated that tens of thousands of residents still rely on the satellite service to bypass state controls. Authorities have reportedly conducted inspections of private homes and rooftops to locate unauthorized equipment.

Earlier this year, Trump and Elon Musk discussed maintaining Starlink access for Iranians during the unrest. Tehran has repeatedly accused Washington of encouraging dissent, though U.S. officials have mostly denied the allegations.

The decision to prioritize Starlink sparked internal debate within U.S. agencies. Some officials argued that shifting resources away from Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) could weaken broader internet access efforts. VPNs had previously played a major role in keeping Iranians connected during earlier protest waves, though VPNs are not effective when the actual internet gets cut.

According to State Department figures, about 30 million Iranians used U.S.-funded VPN services during demonstrations in 2022. During a near-total blackout in June 2025, roughly one-fifth of users were still able to access limited connectivity through VPN tools.

Critics have argued that satellite access without VPN protection may expose users to geolocation risks. After funds were redirected to acquire Starlink equipment, support reportedly lapsed for two of five VPN providers operating in Iran.

A State Department official has stated that the U.S. continues to back multiple technologies, including VPNs alongside Starlink, to sustain people’s internet access amidst the government’s shutdowns.