News

SpaceX Dragon spacecraft caught by robotic space station arm for the last time

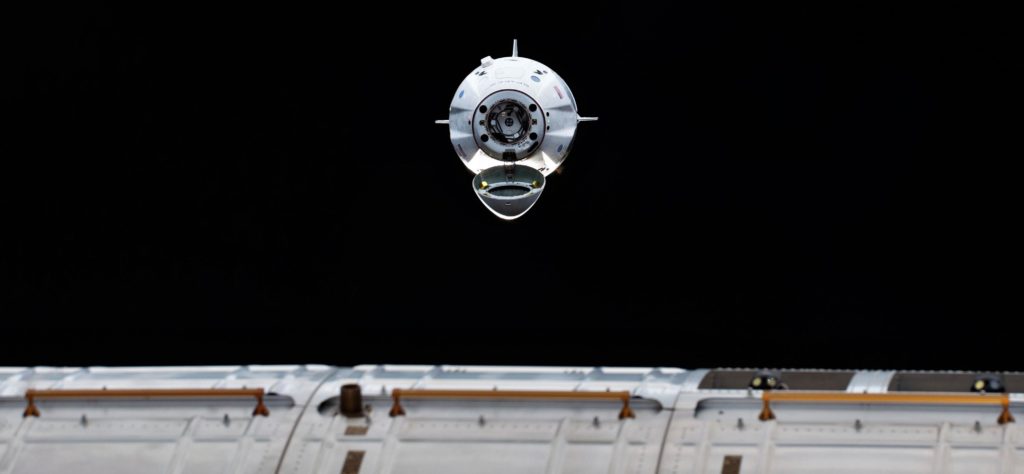

On March 9th, SpaceX’s CRS-20 Cargo Dragon completed an uneventful journey to the International Space Station (ISS), where the spacecraft was successfully captured giant robotic arm for the last time.

Barring several major surprises, Dragon’s March 9th capture was the last time a SpaceX spacecraft berthed with a space station for the foreseeable future – possibly forever. Referring to the process of astronauts manually catching visiting vehicles and installing them on an airlock with a giant, robotic arm, berthing is a much younger technology than docking and was developed as an alternative for a few particular reasons. Perhaps most importantly, the Common Berthing Mechanism (CBM) ports used by Cargo Dragon, Cygnus, and HTV spacecraft are more than 60% wider than standard docking ports. In other words, spacecraft that berth can transport substantially larger pieces of cargo to and from the space station.

More significantly, however, the CBM standard came about in large part due to the decision to assemble the ISS out of 16 pressurized segments, each separately launched into orbit. Measuring about 1.25m (4.2 ft) wide, the CBM ports that connect most of the space station’s 16 livable segments make the ISS far more practical for the astronauts that crew it, while also allowing for larger hardware to be moved between each module. With Crew Dragon, design requirements meant that SpaceX had to move from berthing to docking, a trait SpaceX thus carried over when it chose to base its Cargo Dragon replacement on a lightly-modified Crew Dragon design.

Now verging on routine, Cargo Dragon capsule C112 began its final approach to the International Space Station on March 9th, pausing at set keep-out zones while SpaceX operators waited for NASA and ISS approval to continue. After several stops, Dragon arrived at the last hold point – some 10m (33 ft) away from the station – and NASA astronaut Jessica Meir manually steered Canadarm2 to a successful capture, quite literally grabbing Dragon with a sort of mechanical hand.

At that point, Dragon – like a large ship arriving in port with the help of tugboats – is in the hands of external operators. At the ISS, Canadarm2 essentially flips itself around with Dragon still attached, carefully and slowly mating the spacecraft with one of the station’s free berthing ports. Unlike docking ports, the active part of a berthing port is located on the station’s receiving end, where electromechanical latches and bolts permanently secure the spacecraft to the station and ensure a vacuum seal.

Finally, once berthing is fully complete, ISS astronauts can manually open Dragon’s hatch, giving them access to the two or so metric tons (~4000 lb) of cargo typically contained within. All told, the process of berthing is relatively intensive and expensive in terms of the amount of time station astronauts and NASA ground control must spend to complete a single resupply mission. From start to finish, excluding training, berthing takes a crew of two station astronauts some 9-12 hours of near-continuous work from spacecraft approach to hatch open.

One definite benefit of the docking approach Crew Dragon and Cargo Dragon 2 will use is just how fast it is compared to berthing. Because docking is fundamentally autonomous and controlled by the spacecraft instead of the station, it significantly reduces the workload placed on ISS astronauts. Crew members must, of course, remain vigilant and pay close attention during the critical approach period, particularly with uncrewed Cargo Dragon 2 spacecraft. However, the assumption is always that the spacecraft will independently perform almost all tasks related to docking, short of actually offloading cargo and crew.

For now, CRS-20 will likely be SpaceX’s last uncrewed NASA cargo mission for at six months. CRS-21 – Cargo Dragon 2’s launch debut – is currently scheduled no earlier than (NET) Q4 2020. Nevertheless, Crew Dragon’s next launch – also its astronaut launch debut – could lift off as early as May 2020, just two months from now. With both SpaceX’s crew and cargo missions soon to consolidate around a single spacecraft, the odds are good that Dragon 2 will wind up flying far more than Dragon 1, and the start of its increasingly common launches is just around the corner.

Check out Teslarati’s Marketplace! We offer Tesla accessories, including for the Tesla Cybertruck and Tesla Model 3.

Elon Musk

Tesla showcases Optimus humanoid robot at AWE 2026 in Shanghai

Tesla’s humanoid robot was presented as part of the company’s exhibit at the Shanghai electronics show.

Tesla showcased its Optimus humanoid robot at the 2026 Appliance & Electronics World Expo (AWE 2026) in Shanghai. The event opened Thursday and featured several Tesla products, including the company’s humanoid robot and the Cybertruck.

The display was reported by CNEV Post, citing information from local media outlet Cailian and on-site staff at the exhibition.

Tesla’s humanoid robot was presented as part of the company’s exhibit at the Shanghai electronics show. On-site staff reportedly stated that mass production of the robot could begin by the end of 2026.

Tesla previously indicated that it plans to manufacture its humanoid robots at scale once production begins, with its initial production line in the Fremont Factory reaching up to 1 million units annually. An Optimus production line at Gigafactory Texas is expected to produce 10 million units per year.

Tesla China previously shared a teaser image on Weibo showing a pair of highly detailed robotic hands believed to belong to Optimus. The image suggests a design with finger proportions and structures that closely resemble those of a human hand.

Robotic hands are widely considered one of the most difficult engineering challenges in humanoid robotics. For a system like Optimus to perform complex real-world tasks, from factory work to household activities, the robot would require highly advanced dexterity.

Elon Musk has previously stated that Optimus has the capability to eventually become the first real-world example of a Von Neumann machine, a self-replicating system capable of building copies of itself, even on other planets. “Optimus will be the first Von Neumann machine, capable of building civilization by itself on any viable planet,” Musk wrote in a post on X.

Elon Musk

Tesla Cybercab production line is targeting hundreds of vehicles weekly: report

According to the report, Tesla has been adding staff and installing new equipment at its Austin factory as it prepares to begin Cybercab production.

Tesla is reportedly designing its Cybercab production line to manufacture hundreds of the autonomous vehicles each week once mass production begins. The effort is underway at Gigafactory Texas in Austin as the company prepares to start building the Robotaxi at scale.

The details were reported by The Wall Street Journal, citing people reportedly familiar with the matter.

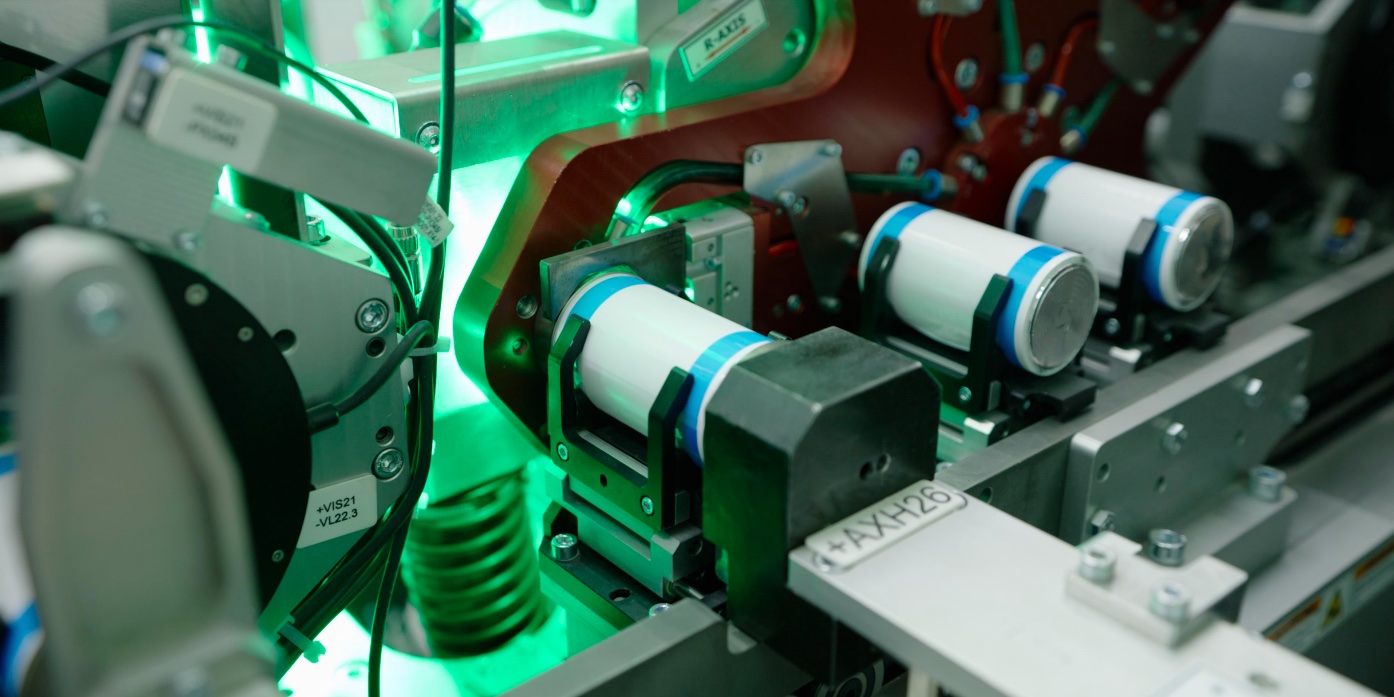

According to the report, Tesla has been adding staff and installing new equipment at its Austin factory as it prepares to begin Cybercab production.

People reportedly familiar with Tesla’s plans stated that the company has been growing its staff and bringing in new equipment to start the mass production of the Cybercab this April.

The Cybercab is Tesla’s upcoming fully autonomous two-seat vehicle designed without a steering wheel or pedals. The vehicle is intended to operate primarily as part of Tesla’s planned Robotaxi ride-hailing network.

“There’s no fallback mechanism here. Like this car either drives itself or it does not drive,” Musk stated during Tesla’s previous earnings call.

Tesla has indicated that Cybercab production could begin as soon as April, though Elon Musk has noted that early production will likely be slow before ramping over time. Musk has stated that the Cybercab’s slow ramp is due in no small part to the fact that it is a completely new vehicle platform.

Tesla’s Cybercab is designed to work with the company’s Full Self-Driving (FSD) system and support its planned autonomous ride-hailing service. The company has suggested that the vehicle could cost under $30,000, making it one of Tesla’s most affordable models if produced at scale. Musk has confirmed in a previous X post that the vehicle will indeed be offered to regular consumers at a price below $30,000.

Musk has previously stated that Tesla could eventually produce millions of Cybercabs annually if demand and production capacity scale as planned.

News

Tesla VP explains latest updates in trade secret theft case

Tesla reportedly caught Matthews copying the tech into machines that were sold to competitors, claiming they lied about doing so for three years, and continued to ship it. That is when Tesla chose to sue Matthews in July 2024 in Federal court, demanding over $1 billion in damages due to trade secret theft.

Tesla Vice President Bonne Eggleston explained the latest updates in a trade secret theft case the company has against a former manufacturing equipment supplier, Matthews International.

Back in 2024, Tesla had filed a lawsuit against Matthews International, alleging that the firm stole trade secrets about battery manufacturing and shared those details with some of Tesla’s competitors.

Early last year, a U.S. District Court Judge denied Tesla’s request to block Matthews International from selling its dry battery electrode (DBE) technology across the world. The judge, Edward Davila, said that the patent for the tech was due to Matthews’ “extensive research and development.”

The two companies’ relationship began back in 2019, as Tesla hired Matthews to help build the equipment for its 4680 battery cell. Tesla shared confidential software, designs, and know-how under strict secrecy rules.

Fast forward a few years, and Tesla reportedly caught Matthews copying the tech into machines that were sold to competitors, claiming they lied about doing so for three years, and continued to ship it. That is when Tesla chose to sue Matthews in July 2024 in Federal court, demanding over $1 billion in damages due to trade secret theft.

Now, the latest twist, as this month, a Judge issued a permanent injunction—a court order banning Matthews from using certain stolen Tesla parts or designs in their machines. Matthews is also officially “liable” for damages. The exact amount would still to be calculated later.

Bonne Eggleston, a VP for Tesla, said on X today that Matthews is a supplier who “exploited customer IP through theft or deception,” and has no place in Tesla’s ecosystem:

Buyer beware: Matthews International stole Tesla’s DBE technology and is now subject to an injunction and liable for damages.

During our work with Matthews, we caught them red-handed copying our technology—including proprietary software and sensitive mechanical designs—into… https://t.co/Toc8ilakeM

— Bonne Eggleston (@BonneEggleston) March 10, 2026

Tesla calls this a big win and warns other companies: “Buyer beware—don’t buy from thieves.”

Matthews hit back with a press release claiming victory. They say an arbitrator ruled they can keep selling their own DBE equipment to anyone and rejected Tesla’s request for a total sales ban. They call Tesla’s claims “nonsense” and insist their 20-year-old tech is independent. Both sides are spinning the same narrow ruling: Matthews can sell their version, but they’re blocked from using Tesla’s specific secrets.

What are Tesla’s Current Legal Options

The case isn’t over—it’s moving to the damages phase. Tesla can:

- Push forward in court or arbitration to calculate and collect huge financial penalties (potentially $1 billion+ if willful theft is proven).

- Enforce the permanent injunction with contempt charges, fines, or even jail time if Matthews violates it.

- Challenge Matthews’ new patents that allegedly copy Tesla’s work, asking courts to invalidate them or add Tesla as co-inventor.

- Seek extra damages, lawyer fees, and possibly punitive awards under the federal Defend Trade Secrets Act and California law.

Tesla could also refer evidence to federal prosecutors for possible criminal trade-secret charges (rare but serious). Settlement is always possible, but Tesla’s fiery public response suggests they want full accountability.

This isn’t just corporate drama. It shows why trade secrets matter even when Tesla open-sources some patents, confidential know-how shared in trust must stay protected. For the EV industry, it’s a reminder: steal from your biggest customer, and you risk losing everything.