SpaceX

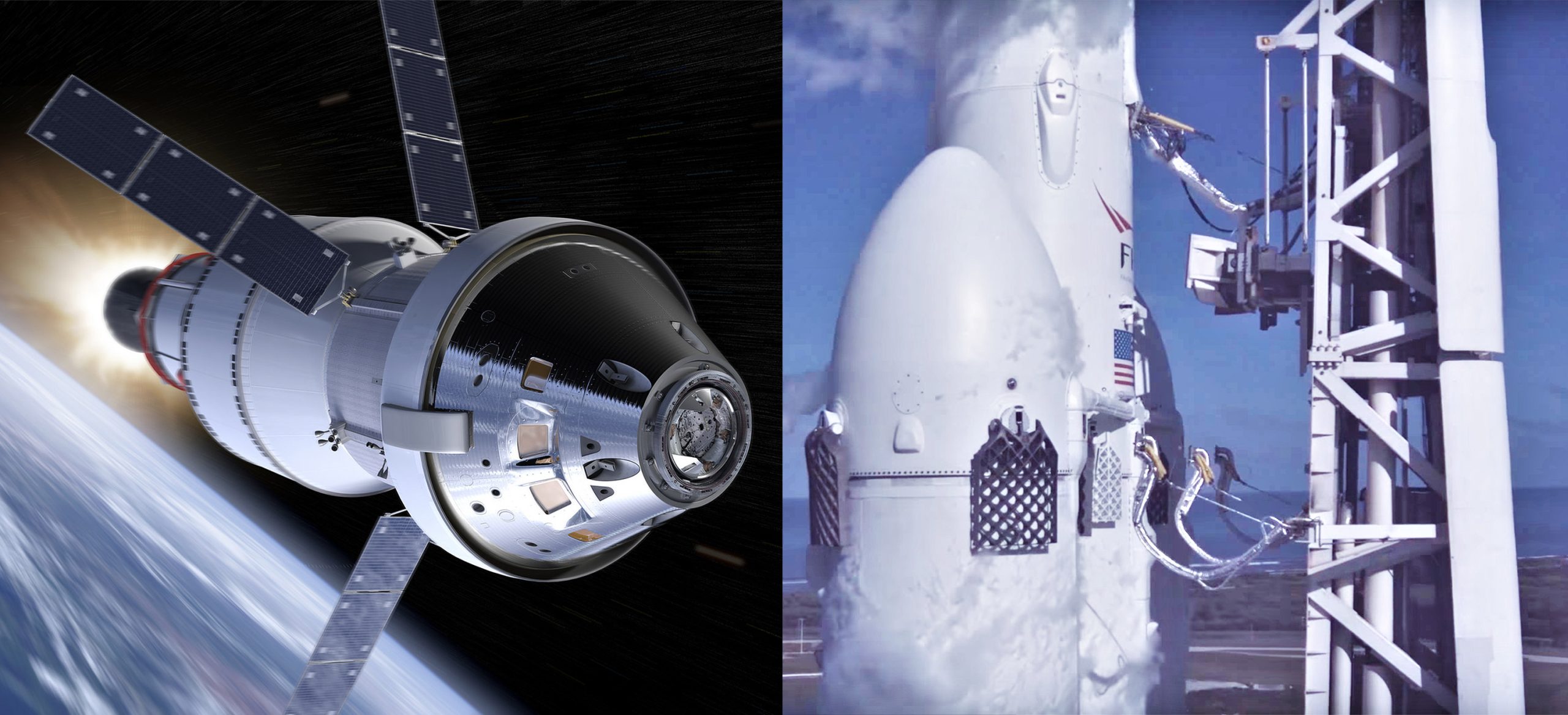

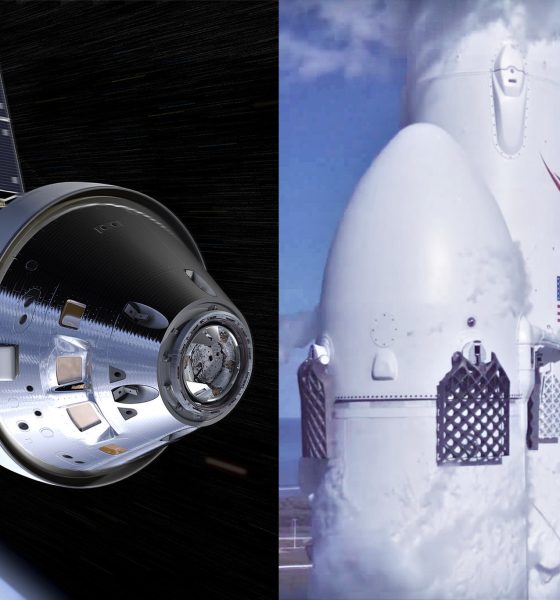

SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy shown launching NASA Orion spacecraft in fan render

A spaceflight fan’s unofficial render has offered the best look yet at what SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy could look like in the unlikely but not impossible event that NASA decides to launch its uncrewed Orion demonstration mission on commercial rockets.

Oddly enough, the thing that most stands out from artist brickmack’s interpretation of Orion and Falcon Heavy is just how relatively normal the large NASA spacecraft looks atop a SpaceX rocket. The render also serves as a visual reminder of just how little SpaceX would necessarily need to change or re-certify before Falcon Heavy would be able to launch Orion. Aside from the fact that NASA’s Launch Services Program (LSP) is not quite ready to certify the full launch vehicle for NASA missions, very few hurdles appear to stand in the way of Orion launching on a commercial rocket – be it on Falcon Heavy or ULA’s Delta IV Heavy.

In a wholly unexpected announcement made by NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine during a March 13th Congressional hearing, the agency leader revealed that NASA was seriously analyzing the possibility of launching Orion’s uncrewed lunar demonstration mission – known as Exploration Mission 1 (EM-1) – on commercial launch vehicles instead of the agency’s own Space Launch System (SLS) rocket.

The purpose: maintain the missions launch schedule – 2020 – in the face of a relentless barrage of delays facing the SLS rocket, the launch debut of which has effectively been slipped almost three years in the last 18 or so months, with the latest launch date now featuring a median target of November 2021. Some subset of NASA leaders, Congressional supporters, and White House officials have clearly begun to accept that SLS/Orion’s major continued delays are simply unacceptable to both the taxpayer and maintaining appearances, despite the fact that those delays continue to make SLS/Orion an extremely successful example of both corporate welfare and a jobs program.

As it currently stands, a median target of November 2021 for the SLS launch debut guarantees that there is almost certainly no chance of the rocket launching at any point in 2020, even if NASA took the extraordinary step of completely cutting a full-length static fire of the entirely unproven rocket prior to its debut. Known as the “Green Run”, the ~8-minute long static fire test is planned to occur at NASA’s Stennis Space Center on the B2 test stand, which NASA – despite continuous criticism from OIG before and after the decision – has spent more than $350M to refurbish. Stennis B2’s refurbishment was effectively completed just two months ago after the better part of seven years of work.

Put simply, even heroics verging on insanity would be unlikely to get SLS prime contractor Boeing to cut ~12 months off of the rocket’s schedule prevent additional unplanned delays in the 18 or so months between now and an even minutely plausible launch debut target. Admittedly, NASA’s proposed commercial alternative for Orion’s lunar launch debut also offers a range of different but equally concerning risks for the program and mission assurance.

Major challenges remain

On one hand, the task of successfully launching NASA’s Orion spacecraft around the Moon with Delta IV Heavy and Falcon Heavy rockets has a lot going for it, regardless of which rockets launch Orion to LEO or launch the fueled upper stage to boost it around the Moon. In 2014, NASA and ULA successfully launched a partial-fidelity Orion spacecraft to an altitude of 3700 miles (~6000 km), testing some of Orion’s avionics, general spacefaring capabilities, and the craft’s heat shield, although Lockheed Martin has since significantly changed the shield’s design and method of production/installation. Regardless, the EFT-1 test flight means that a solution already more or less exists to mate Orion and its service module (ESM) to a commercial rocket and launch the duo into orbit.

If ULA is unable to essentially produce a Delta IV Heavy from scratch in less than 12-18 months, Falcon Heavy would be next in line to launch Orion/ESM, a use-case that might actually be less absurd than it seems. Thanks to the fact that SpaceX’s payload fairing is actually wider than the large Orion spacecraft (5.2 m (17 ft) vs. 5 m (16.5 ft) in diameter), any major risks of radical aerodynamic problems can be largely retired, although that would still need to be verified with models and/or wind-tunnel testing. The only major change that would need to be certified is ensuring that the Falcon second stage is capable of supporting the Orion/ESM payload, weighing at least ~26 metric tons (~57,000 lb) at launch. The heaviest payloads SpaceX has launched thus far were likely its Iridium NEXT missions, weighing around 9600 kg (21,100 lb).

However, the most difficult aspects of Bridenstine’s proposed alternative are centered around the need for the EM-1 Orion spacecraft to somehow dock with a fueled upper stage meant to be launched separately. Orion in its current EM-1 configuration does not currently have the ability to dock with anything on orbit, a challenge that would require Lockheed Martin and subcontractors to find a way to install the proper hardware and computers and develop software that was – prior to this surprise announcement – only planned to fly on EM-3 (NET 2024). As such, Lockheed Martin – notorious for slow progress, cost overruns, and delays throughout the Orion program – would effectively become the critical path in finishing and installing on-orbit docking capabilities on Orion in less than 12-18 months.

The only alternative would be to have either SpaceX or ULA retrofit some sort of docking mechanism onto one of their upper stages, perhaps less difficult than getting Lockheed Martin to work expediently but still a major challenge for such a short developmental timeframe. Put simply, completing the tasks at hand in the time allotted could easily be beyond the capabilities of old-guard NASA contractors like LockMart and Boeing. Ironically, the upper stage that was designed for EM-1 and is already more or less complete – known as the interim cryogenic propulsion stage (ICPS) – is built by Boeing, the same company that has the most to lose if NASA chooses to make the SLS rocket – which Boeing also builds – functionally redundant with a commercial dual-launch alternative.

Second render in this series. Commercial transport for Orion from LEO to TLI in a dual-launch profile (this part is much harder in the near term, really need ACES unless the goal is only a flyby) https://t.co/70eG2i7Axz— Mack Crawford (@brickmack) March 24, 2019

With

Check out Teslarati’s Marketplace! We offer Tesla accessories, including for the Tesla Cybertruck and Tesla Model 3.

Elon Musk

Elon Musk pivots SpaceX plans to Moon base before Mars

The shift, Musk explained, is driven by launch cadence and the urgency of securing humanity’s long-term survival beyond Earth, among others.

Elon Musk has clarified that SpaceX is prioritizing the Moon over Mars as the fastest path to establishing a self-growing off-world civilization.

The shift, Musk explained, is driven by launch cadence and the urgency of securing humanity’s long-term survival beyond Earth, among others.

Why the Moon is now SpaceX’s priority

In a series of posts on X, Elon Musk stated that SpaceX is focusing on building a self-growing city on the Moon because it can be achieved significantly faster than a comparable settlement on Mars. As per Musk, a Moon city could possibly be completed in under 10 years, while a similar settlement on Mars would likely require more than 20.

“For those unaware, SpaceX has already shifted focus to building a self-growing city on the Moon, as we can potentially achieve that in less than 10 years, whereas Mars would take 20+ years. The mission of SpaceX remains the same: extend consciousness and life as we know it to the stars,” Musk wrote in a post on X.

Musk highlighted that launch windows to Mars only open roughly every 26 months, with a six-month transit time, whereas missions to the Moon can launch approximately every 10 days and arrive in about two days. That difference, Musk stated, allows SpaceX to iterate far more rapidly on infrastructure, logistics, and survival systems.

“The critical path to a self-growing Moon city is faster,” Musk noted in a follow-up post.

Mars still matters, but runs in parallel

Despite the pivot to the Moon, Musk stressed that SpaceX has not abandoned Mars. Instead, Mars development is expected to begin in about five to seven years and proceed alongside the company’s lunar efforts.

Musk explained that SpaceX would continue launching directly from Earth to Mars when possible, rather than routing missions through the Moon, citing limited fuel availability on the lunar surface. The Moon’s role, he stated, is not as a staging point for Mars, but as the fastest achievable location for a self-sustaining off-world civilization.

“The Moon would establish a foothold beyond Earth quickly, to protect life against risk of a natural or manmade disaster on Earth,” Musk wrote.

Elon Musk

SpaceX strengthens manufacturing base with Hexagon Purus aerospace deal

The deal adds composite pressure vessel expertise to SpaceX’s growing in-house supply chain.

SpaceX has acquired an aerospace business from Hexagon Purus ASA in a deal worth up to $15 million. The deal adds composite pressure vessel expertise to SpaceX’s growing in-house supply chain.

As per Hexagon Purus ASA in a press release, SpaceX has agreed to purchase its wholly owned subsidiary, Hexagon Masterworks Inc. The subsidiary supplies high-pressure composite storage cylinders for aerospace and space launch applications, as well as hydrogen mobility applications. Masterworks’ hydrogen business is not part of the deal.

The transaction covers the sale of 100% of Masterworks’ shares and values the business at approximately $15 million. The deal includes $12.5 million in cash payable at closing and up to $2.5 million in contingent earn-out payments, subject to customary conditions and adjustments.

Hexagon Purus stated that its aerospace unit has reached a stage where ownership by a company with a dedicated aerospace focus would best support its next phase of growth, a role SpaceX is expected to fill by integrating Masterworks into its long-term supply chain.

The divestment is also part of Hexagon Purus’ broader portfolio review. The company stated that it does not expect hydrogen mobility in North America to represent a meaningful growth opportunity in the near to medium term, and that the transaction will strengthen its financial position and extend its liquidity runway.

“I am pleased that we have found a new home for Masterworks with an owner that views our composite cylinder expertise as world-class and intends to integrate the business into its supply chain to support its long-term growth,” Morten Holum, CEO of Hexagon Purus, stated.

“I want to sincerely thank the Masterworks team for their dedication and hard work in developing the business to this point. While it is never easy to part with a business that has performed well, this transaction strengthens Hexagon Purus’ financial position and allows us to focus on our core strategic priorities.”

News

Starlink goes mainstream with first-ever SpaceX Super Bowl advertisement

SpaceX used the Super Bowl broadcast to promote Starlink, pitching the service as fast, affordable broadband available across much of the world.

SpaceX aired its first-ever Super Bowl commercial on Sunday, marking a rare move into mass-market advertising as it seeks to broaden adoption of its Starlink satellite internet service.

Starlink Super Bowl advertisement

SpaceX used the Super Bowl broadcast to promote Starlink, pitching the service as fast, affordable broadband available across much of the world.

The advertisement highlighted Starlink’s global coverage and emphasized simplified customer onboarding, stating that users can sign up for service in minutes through the company’s website or by phone in the United States.

The campaign comes as SpaceX accelerates Starlink’s commercial expansion. The satellite internet service grew its global user base in 2025 to over 9 million subscribers and entered several dozen additional markets, as per company statements.

Starlink growth and momentum

Starlink has seen notable success in numerous regions across the globe. Brazil, in particular, has become one of Starlink’s largest growth regions, recently surpassing one million users, as per Ookla data. The company has also expanded beyond residential broadband into aviation connectivity and its emerging direct-to-cellular service.

Starlink has recently offered aggressive promotions in select regions, including discounted or free hardware, waived installation fees, and reduced monthly pricing. Some regions even include free Starlink Mini for select subscribers. In parallel, SpaceX has introduced AI-driven tools to streamline customer sign-ups and service selection.

The Super Bowl appearance hints at a notable shift for Starlink, which previously relied largely on organic growth and enterprise contracts. The ad suggests SpaceX is positioning Starlink as a mainstream alternative to traditional broadband providers.