News

SpaceX and NASA accidentally set the stage for a new race to the Moon

Almost entirely driven by chance, SpaceX and NASA may soon find themselves in an unintentional race to return humans to the Moon for the first time in half a century.

Both entities – SpaceX with its next-generation BFR and NASA with its Shuttle-derived SLS – are tentatively targeting 2023 for their similar circumlunar voyages, in which NASA astronauts and private individuals could theoretically travel around the Moon within just months of each other, showcasing two utterly dissimilar approaches to space exploration.

Over the course of no fewer than seven years of development, NASA’s SLS rocket and Orion spacecraft have run into an unrelenting barrage of issues, effectively delaying the system’s launch debut at a rate equivalent to or even faster than the passage of time itself. In other words, every month recently spent working on the vehicle seems to have reliably corresponded with at least an additional month of delays for the launch system.

Why these incessant delays continue to occur is an entire story in itself and demands the acknowledgment of some uncomfortable and inconvenient realities about the state of NASA’s human spaceflight program in the 21st century, but that is a story is for another time.

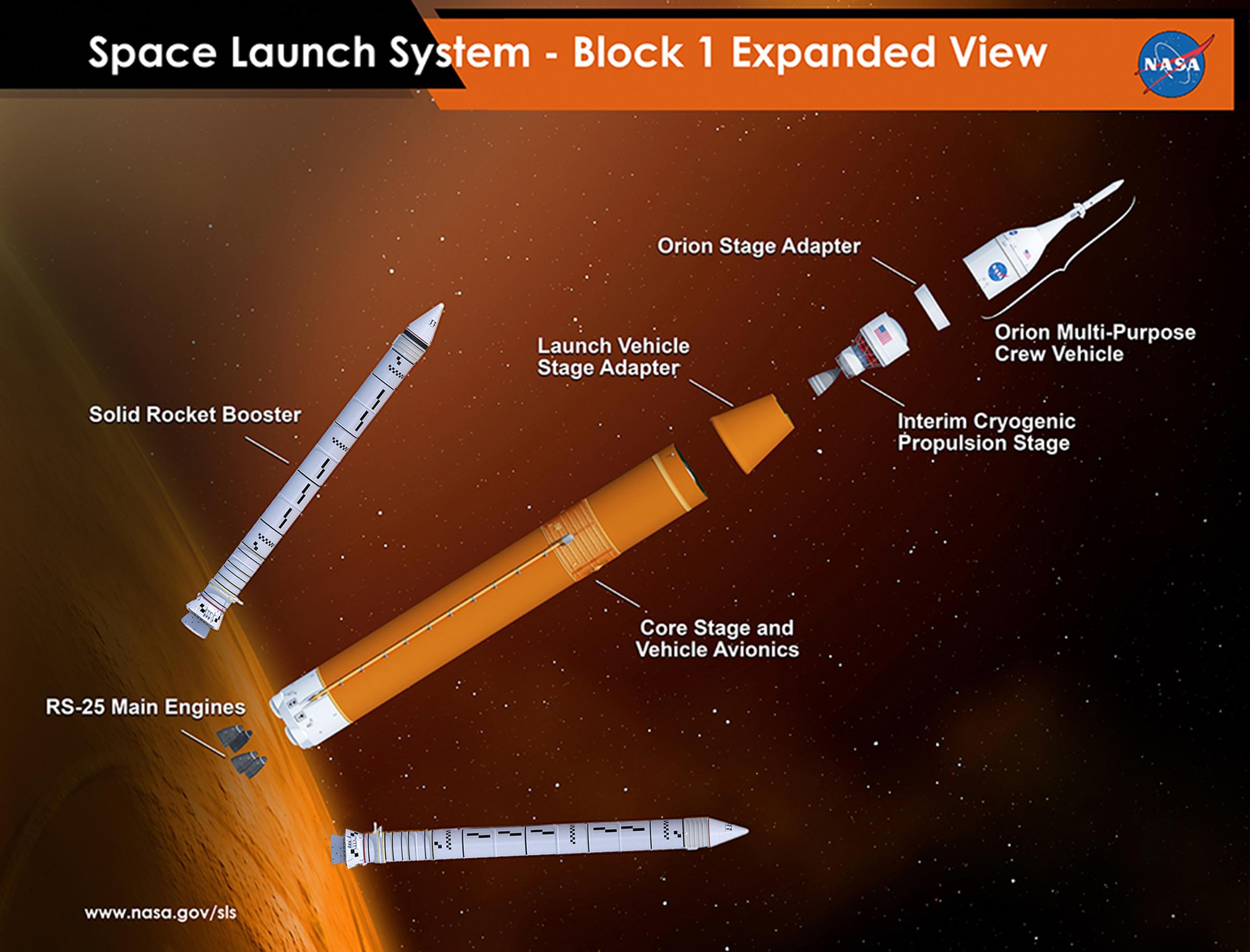

- SLS. (NASA)

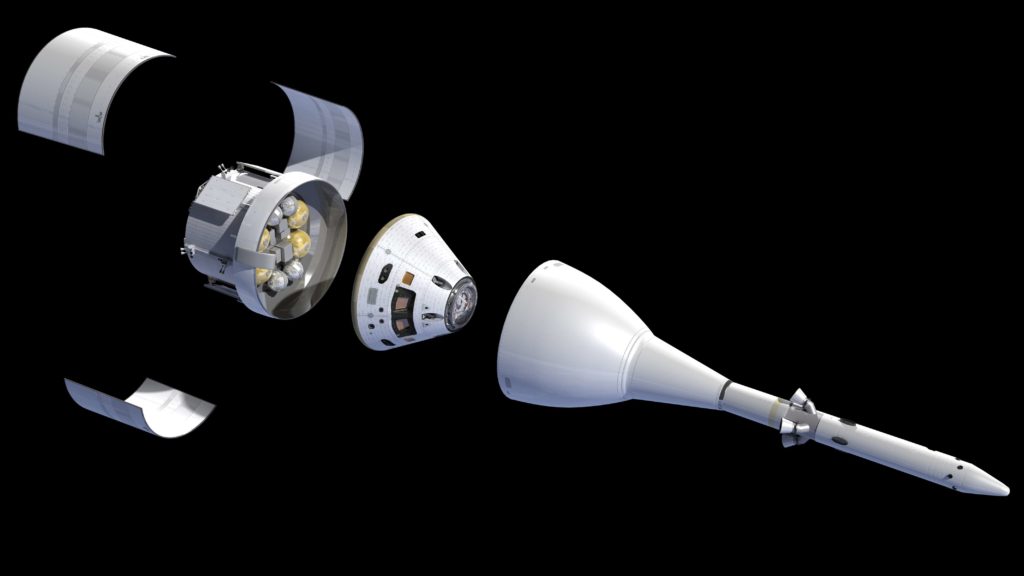

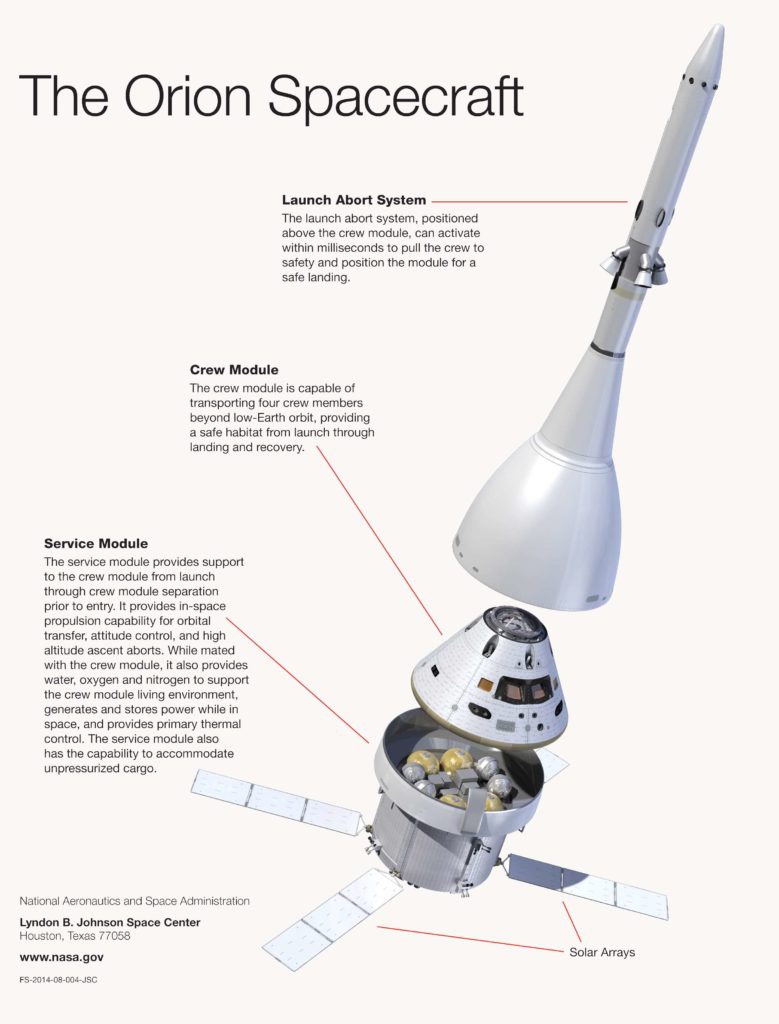

- NASA’s Orion spacecraft, European Service Module, and ICPS upper stage. (NASA)

A different kind of paper rocket

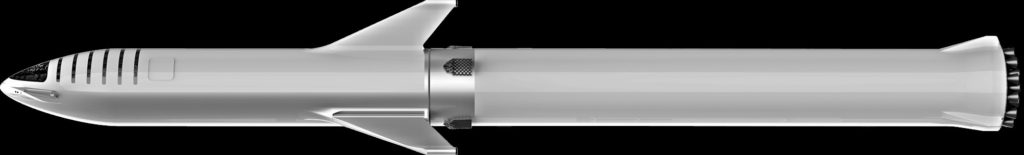

Returning to SLS, a brief overview is in order to properly contextualize what exactly the rocket and spacecraft are and what exactly their development has cost up to now. SLS is comprised of four major hardware segments.

- The Core Stage: A massive liquid hydrogen/liquid oxygen rocket booster, this section is essentially a lengthened version of the retired Space Shuttle’s familiar orange propellant tank, while the stage’s four engines are quite literally taken from stores of mothballed Space Shuttle hardware and will be ingloriously expended after each launch (SLS is 100% expendable).

- Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs): Minimally modified copies of the SRBs used during the Space Shuttle program, SLS’ SRBs have slightly more solid propellant and have had all hints of reusability removed, whereas Space Shuttle boosters deployed parachutes and were reused after landing in the Atlantic Ocean.

- The Upper Stage (Interim Cryogenic Propulsion System, ICPS): ICPS is a slightly modified version of ULA’s off-the-shelf Delta IV upper stage.

- The Orion spacecraft and European Service Module: Borrowing heavily from the Apollo Command and Service Modules that took humanity to the Moon in the 1960s and 70s, Orion has been in funded development in one form or another for more than 12 years, with just one partial flight-test to call its own. Orion’s development has cost the U.S. approximately $16 billion since 2006, with another $4-6 billion expected between now and 2023, a sum that doesn’t account for the costs of production and operations once development is complete.

- The Orion spacecraft and ESM. (NASA)

For the SLS core stage and SRBs, a generous bottom-rung estimate indicates that $14 billion has been spent on the rocket itself between 2011 and 2018, not including many billions more spent refurbishing and modifying the rocket’s aging Saturn and Shuttle-derived launch infrastructure at Kennedy Space Center. Of the many distressing patterns that appear in the above descriptions of SLS hardware, most notable is a near-obsessive dependence upon “heritage” hardware that has already been designed and tested – in some cases even manufactured.

Despite cobbling together or reusing as many mature components, facilities, and workforces as possible and relying on slightly-modified commercial hardware at every turn, SLS and Orion will somehow end up costing the United States more than $30 billion dollars before it has completed a single full launch; potentially rising beyond $40 billion by the time the system is ready to launch NASA astronauts.

Moonward bound

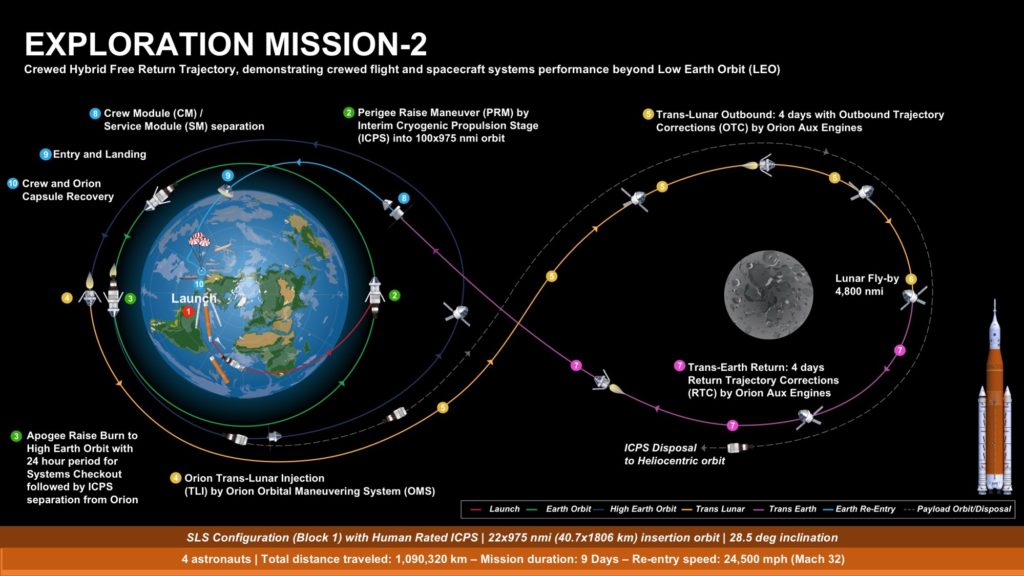

SLS’ first crewed mission, known as Exploratory Mission-2 (EM-2), brings us to the title – NASA’s mission planning has settled on sending a crew of four astronauts on what is known as a Free Lunar Return trajectory in the Orion spacecraft, essentially a single flyby of the Moon. Official NASA statements appear to be sending mixed messages on the schedule for EM-2’s launch, with September 2018 presentations indicating 2022 while a late-August blog post suggests that the crewed circumlunar mission is targeting launch in 2023.

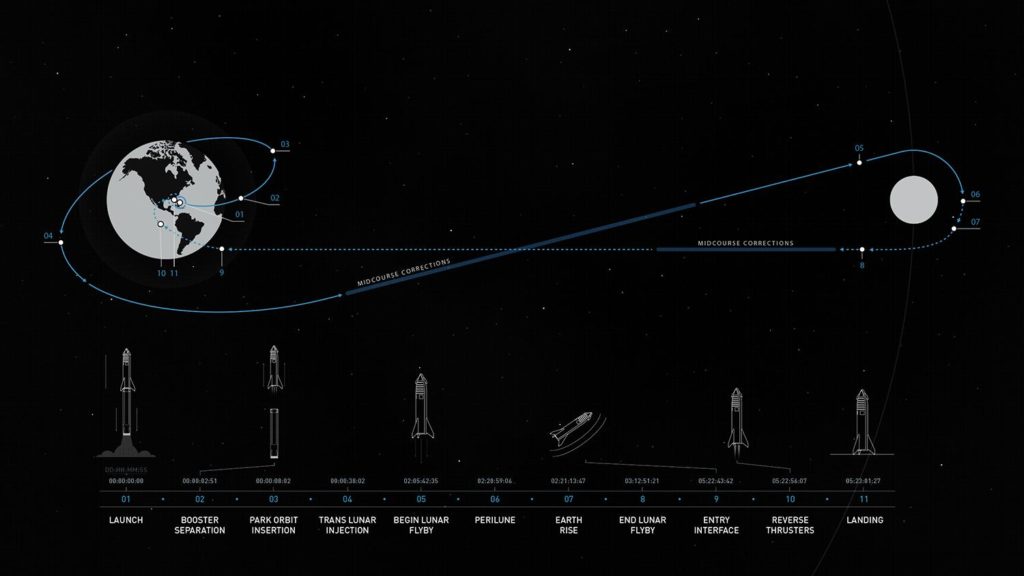

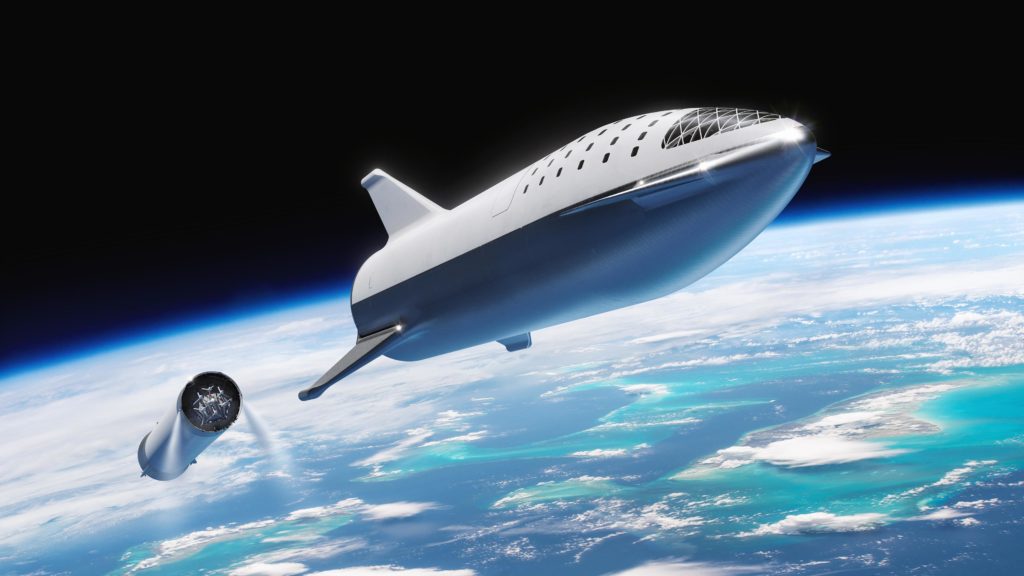

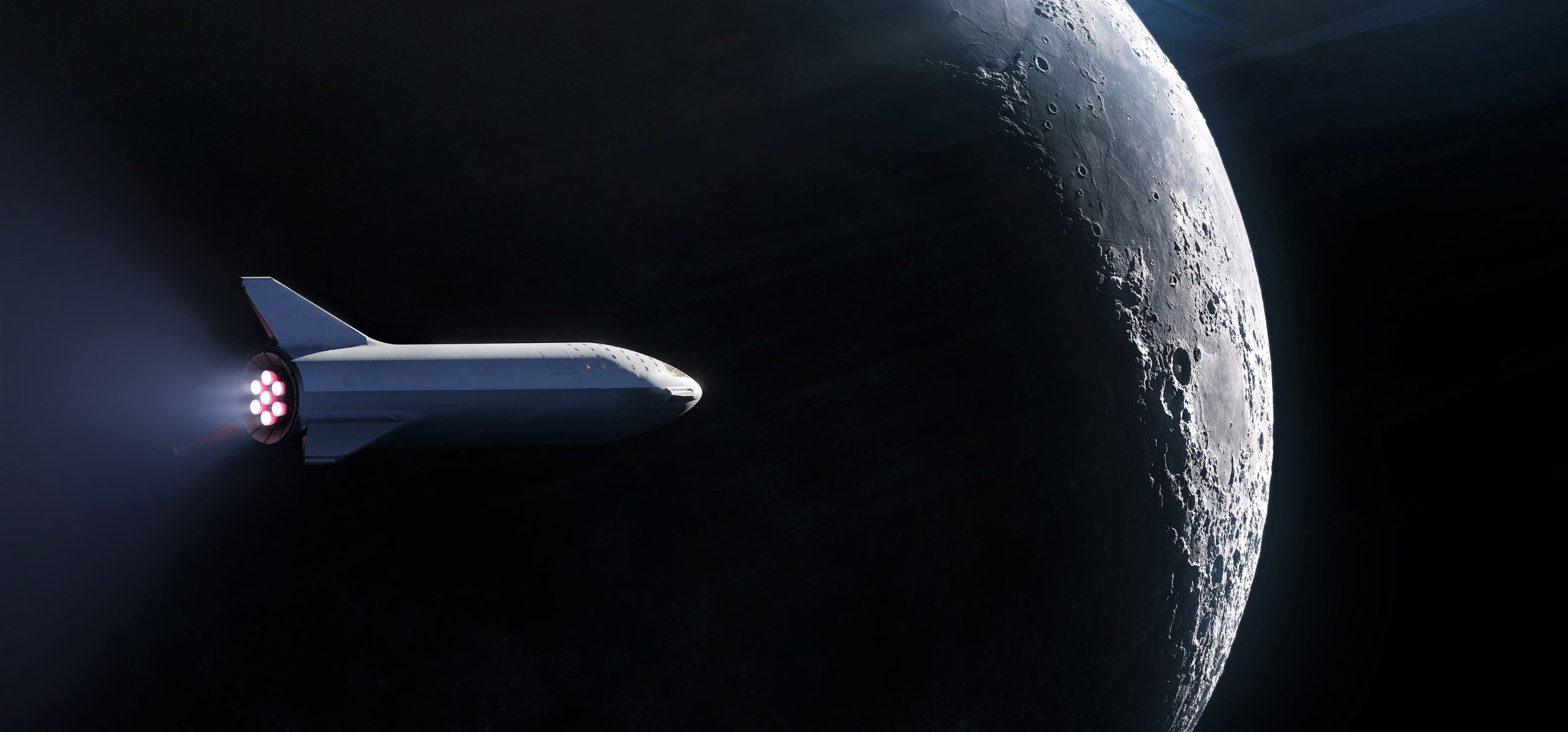

As it happens, SpaceX announced its own plans for a (private) crewed circumlunar voyage less than two weeks ago. Funded in large part by Japanese billionaire Yasuka Maezawa, SpaceX’s hopes to send 10+ people to the Moon on its next-generation BFR launch vehicle, comprised of a fully-reusable booster and spaceship. Deemed Dear Moon by Maezawa, SpaceX is targeting an extremely ambitious launch deadline sometime in 2023, although CEO Elon Musk frankly noted that hitting that 2023 window would require all aspects of BFR booster and spaceship development to proceed flawlessly over the next several years.

Compared to the 10+ years and $30+ billion of development SLS and Orion will have taken before their first full launch, SpaceX is targeting the first orbital BFR test flights as early as 2020 or 2021, self-admittedly optimistic deadlines that will likely slip. Still, betting against SpaceX completing its first BFR launch sometime in the early to mid-2020s for something approximating Musk’s $2-10 billion development cost seems a risky move in the context of SpaceX’s undeniable track record of proving the old-guard wrong.

- NASA’s EM-2 circumlunar voyage. (NASA)

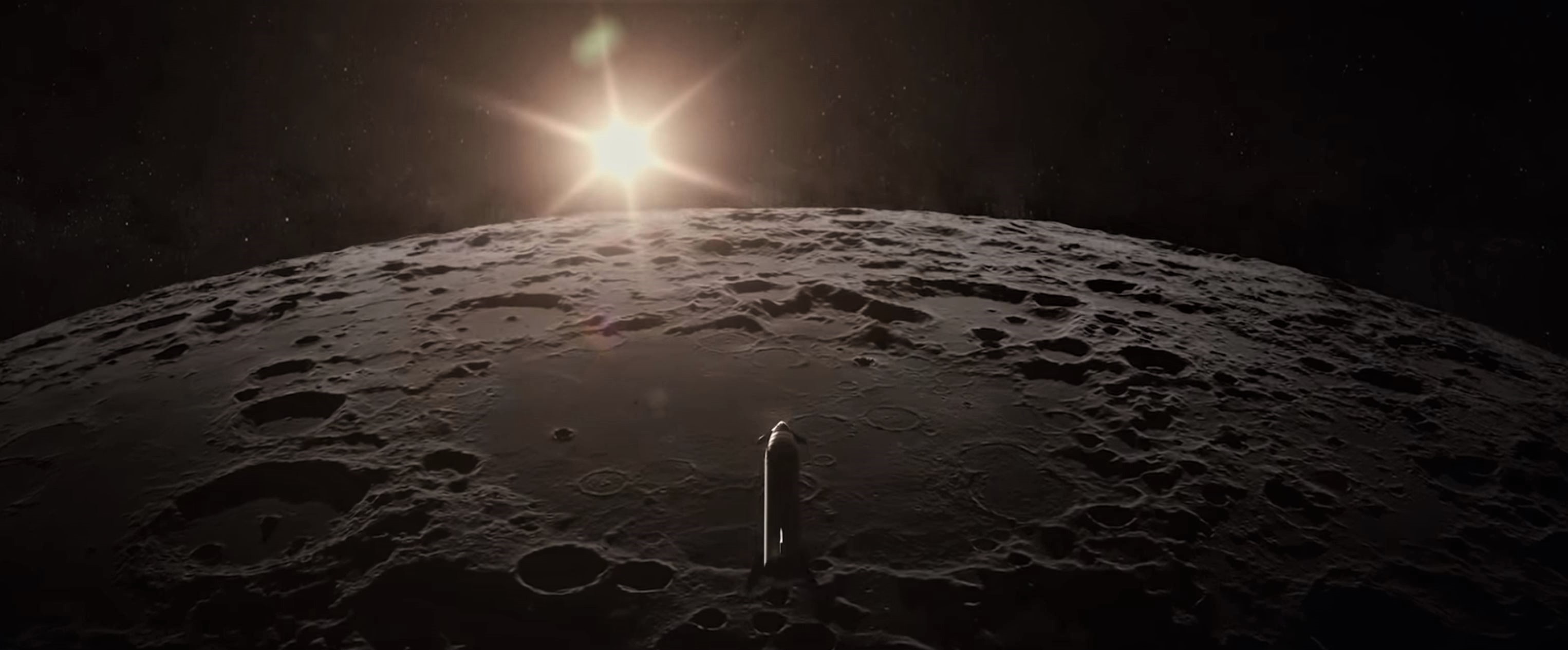

- SpaceX’s own circumlunar trajectory, nearly identical. (SpaceX)

- SLS Block 1. (NASA)

- BFR’s spaceship and booster (now Starship and Super Heavy) separate in a mid-2018 render of the vehicle. (SpaceX)

It must be noted that the apparent alignment of both SpaceX and NASA’s first crewed circumlunar missions with new rockets and spacecraft is a fluke of chance, and the fact that it may or may not take the shape of a second race to the Moon – pitting two dramatically different ideologies and organizational approaches against each other – is purely coincidental.

However, despite the undeniable fact that NASA and SpaceX are deeply and cooperatively involved through Crew and Cargo Dragon and despite Musk’s genuine affirmations of support and admiration for the space agency, it can be almost guaranteed that the world will look on in the 2020s with the same underlying emotions and motivations that were globally present during the Apollo Program. Rather than a battle of economic and nationalistic ideologies, the New Space Race of the 2020s will pit two (publicly) amicable private and public entities against each other at the same time as they work hand-in-hand to deliver crew and cargo to the International Space Station.

- An overview of BFR’s booster and spaceship, now known as Super Heavy and Starship. (SpaceX)

- SpaceX has already completed the first of many carbon-composite sections of its prototype spaceship. (SpaceX)

- SLS’ movable launch pad is very slowly being prepared for a 2020/2021 debut. (Tom Cross)

- SLS undoubtedly has several steps up on BFR in terms of volume of hardware in work, although target launch dates are quite similar for both rockets. (NASA)

Critically, this new “race” will be fairly illusory. Thanks to the fact that the new goal of human spaceflight appears to be the sustainable exploration of the solar system, there will inherently be no Apollo-style finish line for any one company or country or agency to cross. Rather than the Apollo Program’s shortsighted economic motivations and its consequentially abrupt demise, the end-result of this new age of competition will be the establishment of humanity as a (deep) spacefaring species, be it a temporary burst of effort or a permanent human condition.

Buckle up.

For prompt updates, on-the-ground perspectives, and unique glimpses of SpaceX’s rocket recovery fleet check out our brand new LaunchPad and LandingZone newsletters!

Elon Musk

Elon Musk hints Tesla investors will be rewarded heavily

“Hold onto your Tesla stock. It’s going to be worth a lot, I think. That’s my bet,” Musk said.

Elon Musk recently hinted that he believes Tesla investors will be rewarded heavily if they continue to hold onto their shares, and he reiterated that in a new interview that the company released on its social accounts this week.

Musk is one of the most successful CEOs in the modern era and has mammothed competitors on the Forbes Net Worth List over the past year as his holdings in his various companies have continued to swell.

Tesla investors, especially those who have been holding shares for several years, have also felt substantial gains in their portfolios. Over the past five years, the stock is up over 78 percent. Since February 2019, nearly seven years ago to the day, the stock is up over 1,800 percent.

Musk said in the interview:

“Hold onto your Tesla stock. It’s going to be worth a lot, I think. That’s my bet.”

Elon Musk in new interview: “Hold on to your $TSLA stock. It’s going to be worth a lot, I think. That’s my bet.” pic.twitter.com/cucirBuhq0

— Sawyer Merritt (@SawyerMerritt) February 26, 2026

It’s no secret Musk has been extremely bullish on his own companies, but Tesla in particular, because it is publicly traded.

However, the company has so many amazing projects that have an opportunity to revolutionize their respective industries. There is certainly a path to major growth on Wall Street for Tesla through its various future projects, including Optimus, Cybercab, Semi, and Unsupervised FSD.

- Optimus (Tesla’s humanoid robot): Musk has discussed its potential for tasks like childcare, walking dogs, or assisting elderly parents, positioning it as a massive long-term driver of company value.

- Cybercab (Tesla’s robotaxi/autonomous ride-hailing vehicle): a fully autonomous vehicle geared specifically for Tesla’s ride-sharing ambitions.

- Semi (Tesla’s electric truck, with mentions of expansion, like in Europe): brings Tesla into the commercial logistics sector.

- Unsupervised FSD (Full Self-Driving software achieving full autonomy without human supervision): turns every Tesla owner’s vehicle into a fully-autonomous vehicle upon release

These projects specifically are some of the highest-growth pillars Tesla has ever attempted to develop, especially in Musk’s eyes, as he has said Optimus will be the best-selling product of all-time.

Many analysts agree, but the bullish ones, like Cathie Wood of ARK Invest, are perhaps the one who believes Tesla has incredible potential on Wall Street, predicting a $2,600 price target for 2030, but this is not even including Optimus.

She told Bloomberg last March that she believes that the project will present a potential additive if Tesla can scale faster than anticipated.

Cybertruck

Tesla drops latest hint that new Cybertruck trim is selling like hotcakes

According to Tesla’s Online Design Studio, the new All-Wheel-Drive Cybertruck will now be delivered in April 2027. Earlier orders are still slated for early this Summer, but orders from here on forward are now officially pushed into next year:

Tesla’s new Cybertruck offering has had its delivery date pushed back once again. This is now the second time, and deliveries for the newest orders are now pushed well into 2027.

According to Tesla’s Online Design Studio, the new All-Wheel-Drive Cybertruck will now be delivered in April 2027. Earlier orders are still slated for early this Summer, but orders from here on forward are now officially pushed into next year:

🚨 Tesla has updated the $59,990 Cybertruck Dual Motor AWD’s estimated delivery date to April 2027.

First deliveries are still slated for June, but if you order it now, you’ll be waiting over a year.

Demand appears to be off the charts for the new Cybertruck and consumers are… pic.twitter.com/raDCCeC0zP

— TESLARATI (@Teslarati) February 26, 2026

Just three days ago, the initial delivery date of June 2026 was pushed back to early Fall, and now, that date has officially moved to April 2027.

The fact that Tesla has had to push back deliveries once again proves one of two things: either Tesla has slow production plans for the new Cybertruck trim, or demand is off the charts.

Judging by how Tesla is already planning to raise the price based on demand in just a few days, it seems like the company knows it is giving a tremendous deal on this spec of Cybertruck, and units are moving quickly.

That points more toward demand and not necessarily to slower production plans, but it is not confirmed.

Tesla Cybertruck’s newest trim will undergo massive change in ten days, Musk says

Tesla is set to hike the price on March 1, so tomorrow will be the final day to grab the new Cybertruck trim for just $59,990.

It features:

- Dual Motor AWD w/ est. 325 mi of range

- Powered tonneau cover

- Bed outlets (2x 120V + 1x 240V) & Powershare capability

- Coil springs w/ adaptive damping

- Heated first-row seats w/ textile material that is easy to clean

- Steer-by-wire & Four Wheel Steering

- 6’ x 4’ composite bed

- Towing capacity of up to 7,500 lbs

- Powered frunk

Interestingly, the price offering is fairly close to what Tesla unveiled back in late 2019.

Elon Musk

Elon Musk outlines plan for first Starship tower catch attempt

Musk confirmed that Starship V3 Ship 1 (SN1) is headed for ground tests and expressed strong confidence in the updated vehicle design.

Elon Musk has clarified when SpaceX will first attempt to catch Starship’s upper stage with its launch tower. The CEO’s update provides the clearest teaser yet for the spacecraft’s recovery roadmap.

Musk shared the details in recent posts on X. In his initial post, Musk confirmed that Starship V3 Ship 1 (SN1) is headed for ground tests and expressed strong confidence in the updated vehicle design.

“Starship V3 SN1 headed for ground tests. I am highly confident that the V3 design will achieve full reusability,” Musk wrote.

In a follow-up post, Musk addressed when SpaceX would attempt to catch the upper stage using the launch tower’s robotic arms.

“Should note that SpaceX will only try to catch the ship with the tower after two perfect soft landings in the ocean. The risk of the ship breaking up over land needs to be very low,” Musk clarified.

His remarks suggest that SpaceX is deliberately reducing risk before attempting a tower catch of Starship’s upper stage. Such a milestone would mark a major step towards the full reuse of the Starship system.

SpaceX is currently targeting the first Starship V3 flight of 2026 this coming March. The spacecraft’s V3 iteration is widely viewed as a key milestone in SpaceX’s long-term strategy to make Starship fully reusable.

Starship V3 features a number of key upgrades over its previous iterations. The vehicle is equipped with SpaceX’s Raptor V3 engines, which are designed to deliver significantly higher thrust than earlier versions while reducing cost and weight.

The V3 design is also expected to be optimized for manufacturability, a critical step if SpaceX intends to scale the spacecraft’s production toward frequent launches for Starlink, lunar missions, and eventually Mars.