SpaceX

SpaceX & ULA could compete to launch NASA’s Orion spacecraft around the Moon

In barely 48 hours, the future of NASA’s SLS rocket was buffeted relentlessly by a combination of new priorities in the White House’s FY2020 budget request and statements made before Congress by NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine. Contracted by NASA to companies like Boeing, the outright failure of SLS contractors to stem years of launch delays and billions in cost overruns has lead to what can only be described as a possible tipping point, one that could benefit companies like ULA, SpaceX, and Blue Origin.

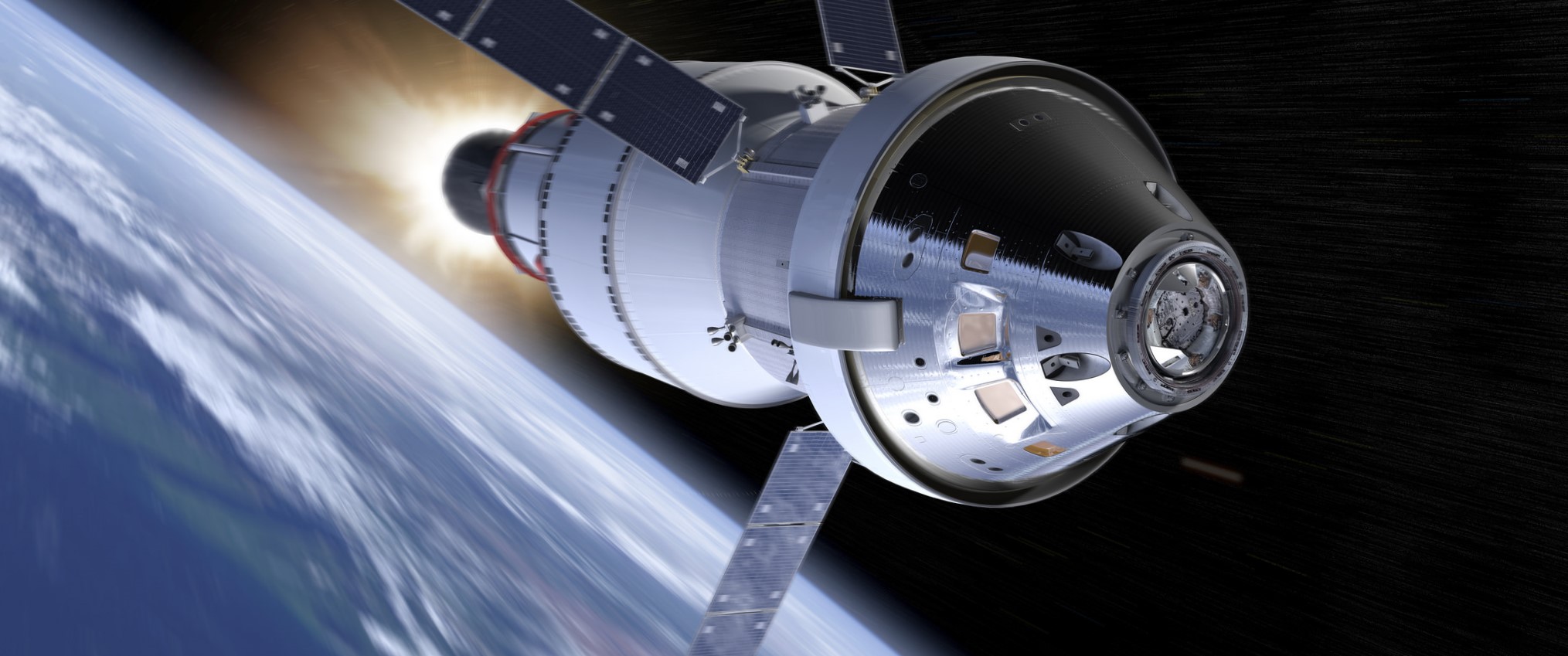

On March 11th, the White House’s 2020 NASA budget request proposed an aggressive curtail of mission options available for the SLS rocket, preferring instead to save hundreds of millions (and eventually billions) of dollars by prioritizing commercial launch vehicles and indefinitely pausing all upgrade work on SLS. On March 13th, Administrator Bridenstine stated before Congress that he was dead-set on ensuring that NASA sticks to a current 2020 deadline for Orion’s first uncrewed circumlunar voyage (EM-1), even if it required using two commercial rockets (either Falcon Heavy or Delta IV Heavy) to send the spacecraft around the Moon next year. In both cases, it’s safe to say that the political tides have somehow undergone a spectacular 180-degree shift in attitude toward SLS, the first salvo in what is guaranteed to be a major political battle.

“Deferred” upgrades

Of the many potential challenges the ides of March have placed before SLS, the first and potentially most significant involves the rocket’s tentative path to future upgrades over the course of its operation. Those upgrades primarily center around the Exploration Upper Stage (EUS) and a new mobile launcher (ML) platform, as well as a longer-term vision known as SLS Block 2. At least with respect to the EUS, NASA (and politicians) were apparently less and less okay with the extraordinary amount of money and time Boeing suggested it would need to develop the new upper stage, to the extent that cutting (or “deferring”) its development could likely save NASA billions of dollars between now and the distant and unstable completion date. Without the EUS, SLS would be dramatically less useful for extreme deep space exploration, effectively the entire purpose of its existence. Instead, the White House included language that would limit SLS launches to crew transfer missions with the Orion spacecraft and nothing more, cutting out heavy cargo missions for science or station-building. Ultimately, those crew transport launches would probably be more than enough to keep SLS Block 1 and Orion busy.

However, two days later, Administrator Bridenstine stated before Congress that he was dead-set on ensuring that NASA sticks to a current 2020 deadline for Orion’s first uncrewed circumlunar voyage (EM-1), going so far as to suggest that NASA was examining the possibility of launching the ~26 ton (57,000 lb) spacecraft on a commercial rocket, followed by a separate launch of a boost stage to send Orion to the Moon. If this were to occur, the consequences could be far-reaching for SLS, potentially delaying the first crewed launch of Orion on SLS until EM-3 and creating a ready-made, one-to-one replacement for SLS at drastically lower costs. At that point, nothing short of political heroics and aggressive bribery could save the SLS program from outright cancellation.

As it stands, the only rockets capable of conceivably supporting a 2020 launch of the 26-ton Orion are ULA’s Delta IV Heavy and SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy, both of which are certified by NASA for (uncrewed) launches. In fact, Falcon 9 was very recently certified by NASA’s Launch Services Program (LSP) to launch the highest priority NASA payloads, signifying the space agency’s growing confidence in SpaceX’s reliability and mission assurance. While the process of certifying Falcon Heavy for an uncrewed Orion launch would be far more complicated than simply grouping Falcon 9’s readiness with Heavy, it would no doubt help that Falcon Heavy is based on hardware (aside from the center core) almost identical to that found on Falcon 9.

The fact that Bridenstine indicated that the primary goal of these potential changes was to speed up EM-1 – an uncrewed demonstrated of Orion functionally similar to Crew Dragon’s recent DM-1 mission – is also significant, as is the fact that such a commercial SLS stand-in would require two separate launches to complete the mission. One launch would place Orion and its service module (ESM) into Low Earth Orbit (LEO), while a second launch would place a partially or fully-fueled upper stage into orbit to propel Orion on a trajectory that would take it around the Moon and back to Earth, similar to the milestone Apollo 8 mission. The need for two launches and the fact that Orion would be uncrewed means that both SpaceX and ULA would be possible candidates for either or both launches, potentially allowing NASA to exploit a competitive procurement process that could lower costs further still.

If Europa Clipper is anything to go off of, launching Orion EM-1 on a commercial rocket could save NASA and the US taxpayer at least $700M (before any potential development costs), aided further by potential competition between ULA and SpaceX. On the other hand, a system that can launch Orion and support EM-1 could fundamentally support all Orion EM missions, of which many are planned. Whether or not Bridenstine and the White House have considered the ramifications, what that translates into is a direct and pressing threat to the continued existence of SLS, with the White House recommending that the rocket be barred from launching large science missions or space station segments as the NASA administrator proposes making it redundant for Orion launches. As Ars Technica’s Eric Berger rightly notes in the tweet at the top of this article, those are the only three conceivable projects where SLS would have any value at all.

If NASA actually went through with this preliminary plan to launch Orion around the Moon on a commercial rocket, they agency would have also fundamentally created a packaged replacement for SLS with a price tag likely 2-5 times cheaper. If Congress had the option to choose between two offerings with similar end-results where one of the two could save the US hundreds of millions of dollars at minimum, it would be almost impossible to argue for the more expensive solution.

Battle of the Heavies

Despite the potential competitive procurement opportunity for a commercial Orion launch, things could get significantly more complicated depending on the political motivations behind the White House and NASA administrator. While Bridenstine explicitly avoided saying as much, the options available to NASA would be ULA’s Boeing-built Delta IV Heavy (DIVH) rocket and SpaceX’s brand new Falcon Heavy. DIVH holds a present-day advantage with active NASA LSP certification for uncrewed spacecraft launches, something Falcon Heavy has yet to achieve.

Nevertheless, it could be the case that NASA, Bridenstine, and/or the White House have a vested interested in potentially replacing SLS for crewed Orion launches entirely. Either way, it’s incredibly unlikely that NASA would launch SLS for the first time ever with astronauts aboard, a massive risk that would also patently contradict the agency’s posture on Commercial Crew launch safety, which has resulted in one uncrewed demo for both Boeing and SpaceX before either be allowed to launch astronauts. NASA also demanded that SpaceX launch Falcon 9 Block 5 seven times in the same configuration meant to launch crew. If NASA is actually interested in at least preserving the option for future crewed launches using the same commercial arrangement, Falcon Heavy is by far the most plausible option Orion’s first uncrewed launch. NASA and SpaceX are deep into the process of human-rating Falcon 9 for imminent Crew Dragon launches with NASA astronauts aboard, meaning that NASA’s human spaceflight certification engineers are about as intimately familiar with Falcon 9 as they possibly can be.

Given that much of Falcon Heavy has direct heritage to Falcon 9, particularly so for the family’s newest Block 5 variant, SpaceX has a huge leg up over ULA’s Delta IV Heavy if it ever came time to certify either heavy-lift rocket for crewed launches. In a third-party study commissioned by NASA and completed in 2009, The Aerospace Corporation concluded that Delta IV Heavy could be human-rated but would require far-reaching modifications to almost every aspect of the rocket’s hardware and software. Most notably, Aerospace found – in a truly ironic twist of fate – that Boeing would likely need to develop a wholly new upper stage for a human-rated Delta IV Heavy, increasing redundancy by increasing the number of RL-10 engines from two to four. As proposed by Boeing, the Exploration Upper Stage – under threat of deferment due to high cost and slow progress – would also feature four RL-10 engines and much of the same upgrades Boeing would need to develop for EUS. Aside from an entirely new upper stage, ULA would also need to develop and qualify an entirely new variant of the RS-68A engine that powers each DIVH booster. Ultimately, TAC believed it would take “5.5 to 7 years” and major funding to human-rate Delta IV Heavy.

Meanwhile, Falcon Heavy already offers multiple-engine-out capabilities, uses the same M1D and MVac engines – as well as an entire upper stage – that are on a direct path to be human-rated later this year, and two side boosters with minimal changes from Falcon 9’s nearly human-rated booster. NASA would still need to analyze the center core variant and stage separation mechanisms, as well as Falcon Heavy as an integrated and distinct system, but the odds of needing major hardware changes would be far smaller than Delta IV Heavy.

Regardless, it will be truly fascinating to see how this wholly unexpected series of events ultimately plays out as Congress and its several SLS stakeholders begin to analyze the options at hand and (most likely) formulate a battle plan to combat the threats now facing the NASA rocket. According to Administrator Bridenstine, NASA will have come to a final decision on how to proceed with Orion EM-1 as soon as a few weeks from now.

Check out Teslarati’s Marketplace! We offer Tesla accessories, including for the Tesla Cybertruck and Tesla Model 3.

Elon Musk

Elon Musk shares updated Starship V3 maiden launch target date

The comment was posted on Musk’s official account on social media platform X.

SpaceX CEO Elon Musk shared a brief Starship V3 update in a post on social media platform X, stating the next launch attempt of the spacecraft could take place in about four weeks.

The comment was posted on Musk’s official account on social media platform X.

Musk’s update suggests that Starship Flight 12 could target a launch around early April, though the schedule will depend on several remaining milestones at SpaceX’s Starbase launch facility in Texas.

Among the key steps is testing and certification of the site’s new launch tower, launch mount, and tank farm systems. These upgrades will support the next generation of Starship vehicles.

Booster 19 is expected to roll to the launch site and be placed on the launch mount before returning to the production facility to receive its 33 Raptor engines. The booster would then return for a static fire test, which could mark the first time a Super Heavy booster equipped with Raptor V3 engines is fired on the pad.

Ship 39 is expected to undergo a similar preparation process. The vehicle will likely return to the production site to receive its six engines before heading to Massey’s test site for static fire testing.

Once both stages are prepared, the booster and ship will roll out to the launch site for the first full stack of a V3 Super Heavy and V3 Starship. A full wet dress rehearsal is expected to follow before any launch attempt.

Elon Musk has previously shared how SpaceX plans to eventually recover Starship’s upper stage using the launch tower’s robotic arms. Musk noted that the company will only attempt to catch the Starship spacecraft after two successful soft landings in the ocean. The approach is intended to reduce risk before attempting a recovery over land.

“Should note that SpaceX will only try to catch the ship with the tower after two perfect soft landings in the ocean. The risk of the ship breaking up over land needs to be very low,” Musk wrote in a post on X.

Such a milestone would represent a major step toward the full reuse of the Starship system, which remains a central goal for SpaceX’s long-term launch strategy.

News

SpaceX President Gwynne Shotwell details xAI power pledge at White House event

The commitment was announced during an event with United States President Donald Trump.

SpaceX President Gwynne Shotwell stated that xAI will develop 1.2 gigawatts of power at its Memphis-area AI supercomputer site as part of the White House’s new “Ratepayer Protection Pledge.”

The commitment was announced during an event with United States President Donald Trump.

During the White House event, Shotwell stated that xAI’s AI data center near Memphis would include a major energy installation designed to support the facility’s power needs.

“As you know, xAI builds huge supercomputers and data centers and we build them fast. Currently, we’re building one on the Tennessee-Mississippi state line. As part of today’s commitment, we will take extensive additional steps to continue to reduce the costs of electricity for our neighbors…

“xAI will therefore commit to develop 1.2 GW of power as our supercomputer’s primary power source. That will be for every additional data center as well. We will expand what is already the largest global Megapack power installation in the world,” Shotwell said.

She added that the system would provide significant backup power capacity.

“The installation will provide enough backup power to power the city of Memphis, and more than sufficient energy to power the town of Southaven, Mississippi where the data center resides. We will build new substations and invest in electrical infrastructure to provide stability to the area’s grid.”

Shotwell also noted that xAI will be supporting the area’s water supply as well.

“We haven’t talked about it yet, but this is actually quite important. We will build state-of-the-art water recycling plants that will protect approximately 4.7 billion gallons of water from the Memphis aquifer each year. And we will employ thousands of American workers from around the city of Memphis on both sides of the TN-MS border,” she noted.

The Ratepayer Protection Pledge was introduced as part of the federal government’s effort to address concerns about rising electricity costs tied to large AI data centers, as noted in an Insider report. Under the agreement, companies developing major AI infrastructure projects committed to covering their own power generation needs and avoiding additional costs for local ratepayers.

Elon Musk

SpaceX to launch Starlink V2 satellites on Starship starting 2027

The update was shared by SpaceX President Gwynne Shotwell and Starlink Vice President Mike Nicolls.

SpaceX is looking to start launching its next-generation Starlink V2 satellites in mid-2027 using Starship.

The update was shared by SpaceX President Gwynne Shotwell and Starlink Vice President Mike Nicolls during remarks at Mobile World Congress (MWC) in Barcelona, Spain.

“With Starship, we’ll be able to deploy the constellation very quickly,” Nicolls stated. “Our goal is to deploy a constellation capable of providing global and contiguous coverage within six months, and that’s roughly 1,200 satellites.”

Nicolls added that once Starship is operational, it will be capable of launching approximately 50 of the larger, more powerful Starlink satellites at a time, as noted in a Bloomberg News report.

The initial deployment of roughly 1,200 next-generation satellites is intended to establish global and contiguous coverage. After that phase, SpaceX plans to continue expanding the system to reach “truly global coverage, including the polar regions,” Nicolls said.

Currently, all Starlink satellites are launched on SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket. The next-generation fleet will rely on Starship, which remains in development following a series of test flights in 2025. SpaceX is targeting its next Starship test flight, featuring an upgraded version of the rocket, as soon as this month.

Starlink is currently the largest satellite network in orbit, with nearly 10,000 satellites deployed. Bloomberg Intelligence estimates the business could generate approximately $9 billion in revenue for SpaceX in 2026.

Nicolls also confirmed that SpaceX is rebranding its direct-to-cell service as Starlink Mobile.

The service currently operates with 650 satellites capable of connecting directly to smartphones and has approximately 10 million monthly active users. SpaceX expects that figure to exceed 25 million monthly active users by the end of 2026.