SpaceX

SpaceX CEO Elon Musk says that BFR could cost less to build than Falcon 9

SpaceX CEO Elon Musk believes that there may be a path for the company to ultimately build the massive Starship spacecraft and Super Heavy booster (formerly BFR) for less than Falcon 9/Falcon Heavy, a rocket 3-9 times smaller than BFR.

While it certainly ranks high on the list of wild and wacky things the CEO has said over the years, there may be a few ways – albeit with healthy qualifications – that Starship/Super Heavy production costs could ultimately compare favorably with SpaceX’s Falcon family of launch vehicles. Nevertheless, there are at least as many ways in which the next-gen rocket can (or should) never be able to beat the production cost of what is effectively a far simpler rocket.

This will sound implausible, but I think there’s a path to build Starship / Super Heavy for less than Falcon 9

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) February 11, 2019

Dirty boosters done dirt cheap

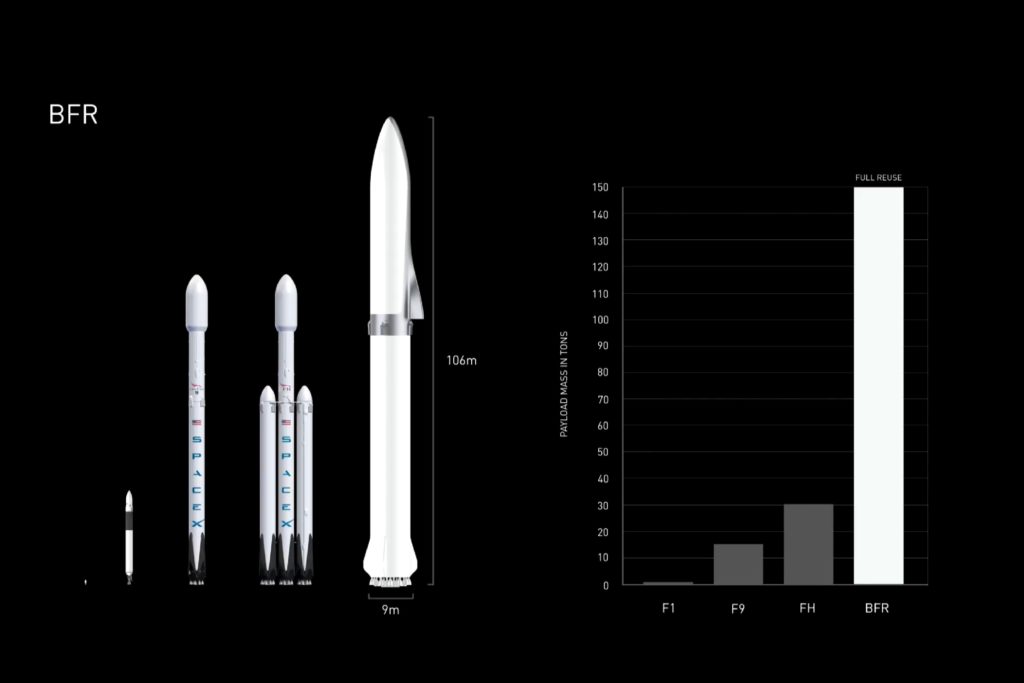

On the one hand, Musk might not necessarily be wrong, especially if one throws the CEO several bones in the interpretation of his brief tweet. BFR at its simplest is going to require a full 38 main rocket engines to achieve its nominal performance goals, 7 on Starship and 31 on Super Heavy. As a dramatically more advanced, larger, and far more complex engine, Raptor will (with very little doubt) cost far more per engine than the relatively simple Merlin 1D. BFR avionics (flight computers, electronics, wiring, harnesses) are likely to be more of a known quantity, meaning that costs will probably be comparable or even lower than Falcon 9’s when measured as a proportion of overall vehicle cost. Assuming that BFR can use the exact same cold gas thruster assemblies currently flying on Falcon 9, that cost should only grow proportionally with vehicle size. Finally, Starship will not require a deployable payload fairing (~10% of Falcon 9’s production cost).

All of those things mean that Starship/Super Heavy will probably be starting off with far better cost efficiency than Falcon 9 was able to, thanks to almost a decade of interim experience both building, flying, and refurbishing the rocket since its 2010 debut. Still, BFR will have to account for entirely new structures like six large tripod fins/wings and their actuators, wholly new thrust structures (akin to Falcon 9’s octaweb) for both stages, and more. Considering Starship on its own, the production of a human-rated spacecraft capable of safely housing dozens of people in space for weeks or months will almost without a doubt rival the cost of airliner production, where a 737 – with almost half a century of production and flight heritage – still holds a price tag of $100-130+ million.

- BFR shown to scale with Falcon 1, 9, and Heavy. (SpaceX)

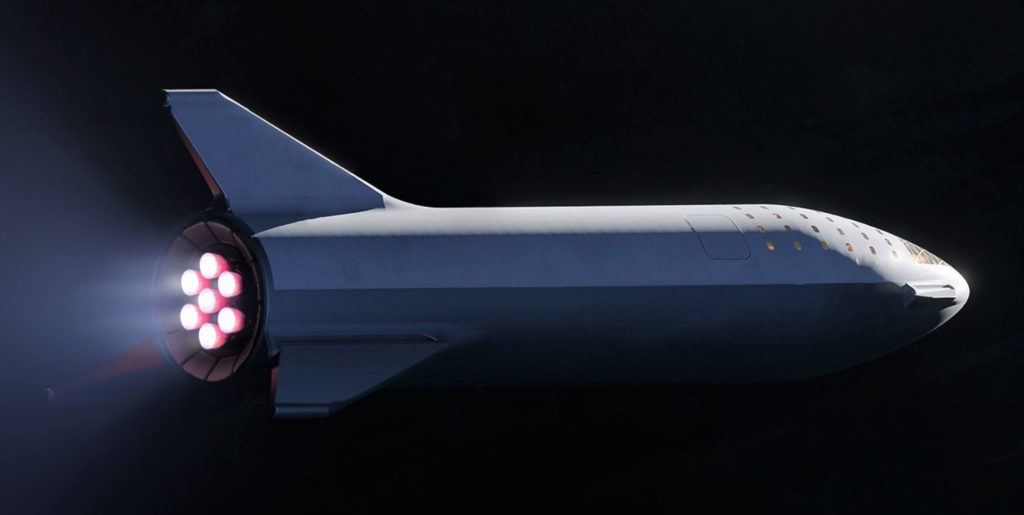

- A September 2018 render of Starship (then BFS) shows one of the vehicle’s two hinged wings/fins/legs. (SpaceX)

- BFR’s booster, now known as Super Heavy. (SpaceX)

- Sadly, this is a not a sight that will greet Falcon 9 booster B1046’s fourth launch – Crew Dragon’s critical In-Flight Abort test. (SpaceX)

Adding one more assumption, the most lenient interpretation of Musk’s tweet assumes that he is really only subjecting the overall structure (sans engines and any crew-relevant hardware) of BFR relative to Falcon 9. In other words, could a ~300-ton stainless steel rocket structure (BFR) cost the same amount or less to fabricate than a ~30-ton aluminum-lithium alloy rocket structure (Falcon 9/Heavy)? From the very roughest of numerical comparisons, Musk estimated the cost of the stainless steel alloys (300-series) to be used for BFR at around $3 per pound ($6.60/kg), while aluminum-lithium alloys used in aerospace (and on Falcon 9) are sold for around $20/lb ($44/kg)*. As such, simply buying the materials to build the basic structures of BFR and Falcon 9 would cost around and $7.5M and $5M, respectively.

Assuming that the process of assembling, welding, and integrating Starship and Super Heavy structures is somehow 5-10 times cheaper, easier, and less labor-intensive, it’s actually not inconceivable that the cost of building BFR’s structure could ultimately compete with Falcon 9 after production has stabilized after the new rocket’s prototyping phase is over and manufacturing processes are mature.

*Very rough estimate, difficult to find a public cost per unit mass from modern Al-Li suppliers

Costs vs. benefits

On the opposite hand, stainless steel rockets do not have a history of being uniquely cost-effective relative to vehicles using alternative materials. The only orbital-class launch vehicles to use stainless steel (and balloon) tanks are the Atlas booster and the Centaur upper stage, with Atlas dating back to the late 1950s and Centaur beginning launches in the early ’60s. Stainless steel Atlas launches ended in 2005 with the final Atlas III mission, while multiple forms of Centaur continue to fly regularly on ULA’s Atlas V and Delta IV.

Based on a 1966 contract between NASA and General Dynamics placed shortly after Centaur’s tortured development had largely been completed, Centaur upper stages were priced around $25M apiece (2018 USD). In 1980, the hardware for a dedicated Atlas-Centaur launch of a ~1500 kg Comstar I satellite to GTO cost the US the 2018 equivalent of a bit less than $40M ($71M including miscellaneous administrative costs) – $22.4M for Centaur and $17.6M for Atlas. For Atlas, the rocket’s airframe (tanks and general structure) was purchased for around $8.5M. That version of Atlas-Centaur (Atlas-SLV3D Centaur-D1A) was capable of lifting around 5100 kg (11,250 lb) into Low Earth Orbit (LEO) and 1800 kg (~4000 lb) to geostationary transfer orbit (GTO), while it stood around 40m (130 ft) tall, had a tank diameter of 3.05m (10 ft), and weighed ~150t (330,000 lb) fully fueled.

- Atlas shows off its shiny steel balloon tanks. (SDASM)

- The original space-faring Atlas, known as SM-65, seen here with a Mercury space capsule. (NASA)

- A Centaur upper stage is pictured here in 1964. (NASA)

- Atlas SLV3D is pictured here launching a Comstar I satellite.

- A Falcon 9 booster is seen here near the end of its tank welding, just prior to painting. (SpaceX)

- An overview of SpaceX’s Hawthorne factory floor in early 2018. (SpaceX)

In a very loose sense, that particular stainless steel Atlas variant was about half as large and half as capable as the first flight-worthy version of Falcon 9 at roughly the same price at launch ($60-70M). What does this jaunt through the history books tell us about the prospects of a stainless steel Starship and Super Heavy? Well, not much. The problem with trying to understand and pick apart official claims about SpaceX’s next-generation launch architecture is quite simple: only one family of rockets in the history of the industry (Atlas) regularly flew with stainless steel propellant tanks, a half-century lineage that completed its final launch in 2005.

Generally speaking, an industrial sample size of more or less one makes it far from easy to come to any particular conclusions about a given technology or practice, and SpaceX – according to CEO Elon Musk – fully intends to push past the state of the art of stainless steel rocket tankage with BFR. Ultimately, American Marietta/Martin Marietta/Lockheed Martin was never able to produce launch vehicle variants of the stainless steel Atlas family at a cost more than marginally competitive with Falcon 9, despite the latter rocket’s use of a far more expensive metal alloy throughout its primary tanks and structure.

At least 10X cheaper

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) February 11, 2019

At some point, it’s even worth asking whether the per-unit cost of Starship and Super Heavy should be relevant at all to their design and construction, at least within reason. If the goal of BFR is to drastically lower the cost of launch by radically improving the ease of reuse, it would be truly bizarre (and utterly unintuitive) if those goals could somehow be achieved without dramatically raising the cost of initial hardware procurement. Perhaps the best close comparison to BFR’s goals, modern airliners are eyewateringly expensive ($100-500M apiece) as a consequence of the extraordinary reliability, performance, efficiency, and longevity customers and regulatory agencies demand from them, although those costs are admittedly not the absolute lowest they could be in a perfect manufacturing scenario.

At the end of the day, it appears that Musk is increasingly of the opinion that the pivot to stainless steel could ultimately make BFR simultaneously “better, faster, [&] cheaper”. However improbable that may be, if it does turn out to be the case, Starship and Super Heavy could be an unfathomable leap ahead for reliable and affordable access to space. It could also be another case of Musk’s excitement and optimism getting the better of him and hyping a given product well beyond what it ultimately is able to achieve. Time will tell!

Check out Teslarati’s newsletters for prompt updates, on-the-ground perspectives, and unique glimpses of SpaceX’s rocket launch and recovery processes!

Elon Musk

Elon Musk denies Starlink’s price cuts are due to Amazon Kuiper

“This has nothing to do with Kuiper, we’re just trying to make Starlink more affordable to a broader audience,” Musk wrote in a post on X.

Elon Musk has pushed back on claims that Starlink’s recent price reductions are tied to Amazon’s Kuiper project.

In a post on X, Musk responded directly to a report suggesting that Starlink was cutting prices and offering free hardware to partners ahead of a planned IPO and increased competition from Kuiper.

“This has nothing to do with Kuiper, we’re just trying to make Starlink more affordable to a broader audience,” Musk wrote in a post on X. “The lower the cost, the more Starlink can be used by people who don’t have much money, especially in the developing world.”

The speculation originated from a post summarizing a report from The Information, which ran with the headline “SpaceX’s Starlink Makes Land Grab as Amazon Threat Looms.” The report stated that SpaceX is aggressively cutting prices and giving free hardware to distribution partners, which was interpreted as a reaction to Amazon’s Kuiper’s upcoming rollout and possible IPO.

In a way, Musk’s comments could be quite accurate considering Starlink’s current scale. The constellation currently has more than 9,700 satellites in operation today, making it by far the largest satellite broadband network in operation. It has also managed to grow its user base to 10 million active customers across more than 150 countries worldwide.

Amazon’s Kuiper, by comparison, has launched approximately 211 satellites to date, as per data from SatelliteMap.Space, some of which were launched by SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket. Starlink surpassed that number in early January 2020, during the early buildout of its first-generation network.

Lower pricing also aligns with Starlink’s broader expansion strategy. SpaceX continues to deploy satellites at a rapid pace using Falcon 9, and future launches aboard Starship are expected to significantly accelerate the constellation’s growth. A larger network improves capacity and global coverage, which can support a broader customer base.

In that context, price reductions can be viewed as a way to match expanding supply with growing demand. Musk’s companies have historically used aggressive pricing strategies to drive adoption at scale, particularly when vertical integration allows costs to decline over time.

Elon Musk

SpaceX secures FAA approval for 44 annual Starship launches in Florida

The FAA’s environmental review covers up to 44 launches annually, along with 44 Super Heavy booster landings and 44 upper-stage landings.

SpaceX has received environmental approval from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to conduct up to 44 Starship-Super Heavy launches per year from Kennedy Space Center Launch Complex 39A in Florida.

The decision allows the company to proceed with plans tied to its next-generation launch system and future satellite deployments.

The FAA’s environmental review covers up to 44 launches annually, along with 44 Super Heavy booster landings and 44 upper-stage landings. The approval concludes the agency’s public comment period and outlines required mitigation measures related to noise, emissions, wildlife, and airspace management.

Construction of Starship infrastructure at Launch Complex 39A is nearing completion. The site, previously used for Apollo and space shuttle missions, is transitioning to support Starship operations, as noted in a Florida Today report.

If fully deployed across Kennedy Space Center and nearby Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Starship activity on the Space Coast could exceed 120 launches annually, excluding tests. Separately, the U.S. Air Force has authorized repurposing Space Launch Complex 37 for potential additional Starship activity, pending further FAA airspace analysis.

The approval supports SpaceX’s long-term strategy, which includes deploying a large constellation of satellites intended to power space-based artificial intelligence data infrastructure. The company has previously indicated that expanded Starship capacity will be central to that effort.

The FAA review identified likely impacts from increased noise, nitrogen oxide emissions, and temporary airspace closures. Commercial flights may experience periodic delays during launch windows. The agency, however, determined these effects would be intermittent and manageable through scheduling, public notification, and worker safety protocols.

Wildlife protections are required under the approval, Florida Today noted. These include lighting controls to protect sea turtles, seasonal monitoring of scrub jays and beach mice, and restrictions on offshore landings to avoid coral reefs and right whale critical habitat. Recovery vessels must also carry trained observers to prevent collisions with protected marine species.

Elon Musk

Elon Musk reiterates rapid Starship V3 timeline with next launch in sight

Musk shared the update in a brief post on X, writing, “Starship flies again next month.”

Elon Musk has confirmed that Starship will fly again next month, reiterating SpaceX’s aggressive timeline for the first launch of its Starship V3 rocket.

Musk shared the update in a brief post on X, writing, “Starship flies again next month.” The CEO’s post was accompanied by a video of Starship’s Super Heavy booster being successfully caught by a launch tower in Starbase, Texas.

The timeline is notable. In late January, Musk stated that Starship’s next flight, Flight 12, was expected in about six weeks. This placed the expected mission date sometime in March. That estimate aligned with SpaceX’s earlier statement that Starship’s 12th flight test “remains targeted for the first quarter of 2026.”

If the vehicle does indeed fly next month, it would mark the debut of Starship V3, the upgraded platform expected to feature the rocket’s new Raptor V3 engines.

Raptor V3 is designed to deliver significantly higher thrust than earlier versions while reducing cost and weight. Starship V3 itself is expected to be optimized for manufacturability, a critical step if SpaceX intends to scale production toward frequent launches for Starlink, lunar missions, and eventually Mars.

Starship V3 is widely viewed as the version that transitions the program from experimental testing to true operational scaling. Previous iterations have completed multiple integrated flight tests, with mixed outcomes but steady progress. Expectations are high that SpaceX is now working on Starship’s refinement.

An aggressive launch schedule supports several priorities at once. It advances Starlink’s next-generation satellite deployment, supports NASA’s lunar ambitions under Artemis, and keeps SpaceX on track for its longer-term Moon and Mars objectives.