News

(Updated) SpaceX’s next launch is a first step to rival Comcast and Time Warner

Updated February 21: Due to strong upper-level winds, SpaceX has postponed the launch to the same time on Thursday, 6:17 a.m. PST, 9:17 EST. CEO Elon Musk took to Twitter to address the delay, “High altitude wind shear data shows a probable 2% load exceedance. Small, but better to be paranoid.”

Update: SpaceX has delayed the launch of PAZ and its Starlink prototype satellites from Sunday, February 18 to Wednesday the 21st in order to complete additional tests and checks of an upgraded payload fairing. Wednesday’s new instantaneous launch window remains unchanged – 6:17 a.m. PST, 9:17 EST.

Standing down today due to strong upper level winds. Now targeting launch of PAZ for February 22 at 6:17 a.m. PST from Vandenberg Air Force Base.

— SpaceX (@SpaceX) February 21, 2018

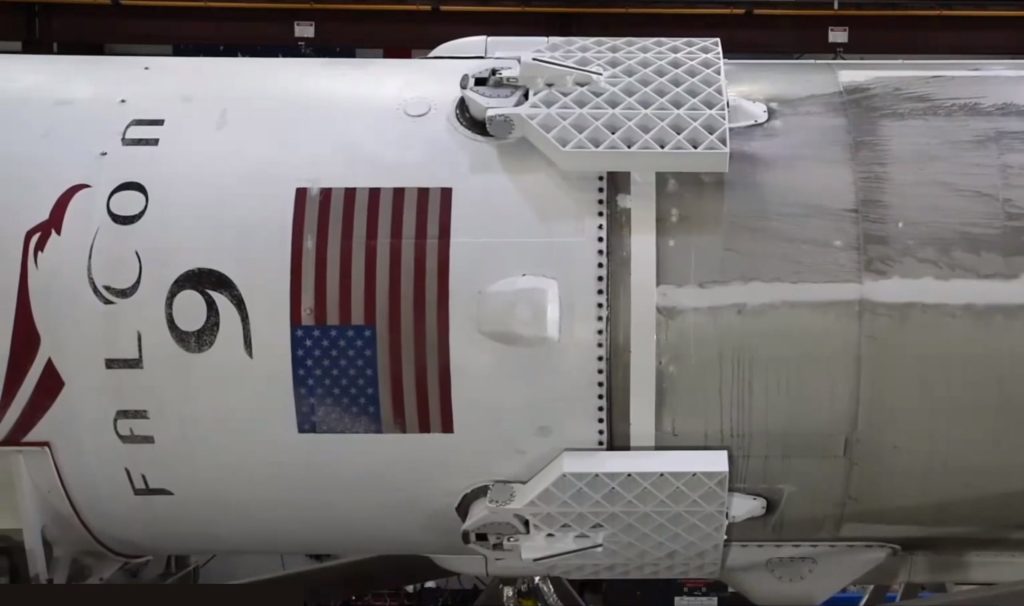

Not long after SpaceX’s recent, flawless Falcon Heavy debut, the company has completed a successful static fire of a flight-proven Falcon 9 on the West coast. SpaceX is preparing to send the Spanish government’s PAZ imaging satellite skyward aboard the same rocket that launched Formosat-5 for the Taiwanese government in August 2017.

Amazingly, this means that three of the four launches conducted by SpaceX in the last two months will have made use of reused Falcon 9 boosters, something I am choosing to take as foreshadowing for the coming months. By all appearances, the rocket company has been eminently successful in enacting a true industrial phase change towards the acceptance of flight-proven rocketry – a hard-earned achievement made possible by a combination of incredible reliability and unexpectedly positive responses from government agencies like NASA and the USAF.

- SpaceX is readying one of three flightworthy reused boosters for its final flight, NET June 4. (SpaceX)

- GovSat-1’s sooty booster from late January 2018. (Tom Cross)

- Falcon Heavy’s incredible debut also featured two flight-proven boosters – the side cores were converted from reused Falcon 9s. (Bill Carton)

A relatively light payload, PAZ weighs in just shy of 1400 kg. However, despite a lack of confirmation, it is known that riding along with the imaging satellite are two highly significant prototype satellites, built by SpaceX itself. Deemed Microsat 2A and 2B in FCC licensing applications, the small 400 kg satellites will act as SpaceX’s first-ever flight test of integrated satellite hardware – a massive step towards realizing the company’s dream of Starlink, a global internet constellation meant to provide service of the same caliber (or better…) as providers like Comcast, Time Warner, and others. This will be a major moment if successful, and will make SpaceX the first US company to successfully launch its first prototype internet satellites intended for low Earth orbit (200-1000 miles above Earth), a factor that would make them far more viable as a competitive alternative to ground-based internet than the current heavyweights in geostationary orbit (30,000+ miles above Earth).

Those distances are crucial: such a long distance between user and terminal (60,000+ miles round trip) results in what the average person would consider “lag” or simply unresponsive internet, where actions take as long as several seconds to register (such as clicking a link). This makes things like gaming, video chat, and more effectively unusable. However, thanks to the miniaturization enabled by the relentless progress of electronics technologies, tiny satellites (100-500 kg) with electric propulsion are rapidly becoming a viable alternative and threat to the massive (4000-8000 kg) communications satellites placed into geostationary orbit. Through mass production and lower costs to orbit, a giant network of magnitudes smaller satellites can realistically beat those giant satellites by being closer to the Earth. This means that more satellites in a given network will more frequently reenter the Earth’s atmosphere and be destroyed, requiring the constant launch of reinforcements, but this new paradigm is actually a viable strategy.

A beautiful string of Iridium NEXT satellites deployed into the sunrise. (SpaceX)

SpaceX’s own Microsats, prototypes for a constellation likely to be named Starlink, are quite possibly the most promising entrants among a sea of interested constellation operators. With the addition of laser-based communications links between each or most of the Starlink satellites planned to be placed in orbit, SpaceX’s constellation will be truly unique in its extreme flexibility as a giant, global mesh network.

By using lasers, latency (lag) will be far less significant and will enable SpaceX to distribute its network’s availability beyond the capability of any individual satellite, known as a decentralized network. As always, SpaceX’s choice to pursue such a configuration is extraordinarily ambitious. Still, the very fact that Microsat 2A and 2B are scheduled for launch just days from now suggests that the company’s near-silent satellite development program, employing several hundred people all over the West coast, has seen some considerable successes. In other words, it’s likely not a coincidence that the first flight test of a Starlink satellite will actually feature two satellites – one cannot test laser interlinks with just one satellite.

All things considered, fingers crossed for SpaceX on this flight-proven commercial mission. If all goes well with both PAZ and the Starlink prototypes, SpaceX will be one huge step closer to being able to provide truly universal, affordable, and high-quality internet.

Stay with us on Twitter and Instagram as Teslarati’s West Coast photojournalist, Pauline Acalin, will bring us on the ground coverage at California’s Vandenberg Air Force Base ahead of, and on the day of, the PAZ mission.

Follow along live as we cover these exciting proceedings live on social media!

Teslarati – Instagram – Twitter

Pauline Acalin – Twitter

Eric Ralph – Twitter

News

Tesla launches in India with Model Y, showing pricing will be biggest challenge

Tesla finally got its Model Y launched in India, but it will surely come at a price for consumers.

Tesla has officially launched in India following years of delays, as it brought its Model Y to the market for the first time on Tuesday.

However, the launch showed that pricing is going to be its biggest challenge. The all-electric Model Y is priced significantly higher than in other major markets in which Tesla operates.

On Tuesday, Tesla’s Model Y went up for sale for 59,89,000 rupees for the Rear-Wheel Drive configuration, while the Long Range Rear-Wheel Drive was priced at 67,89,000.

This equates to $69,686 for the RWD and $78,994 for the Long Range RWD, a substantial markup compared to what these cars sell for in the United States.

🚨 Here’s the difference in price for the Tesla Model Y in the U.S. compared to India.

🚨 59,89,000 is $69,686

🚨 67,89,000 is $78,994 pic.twitter.com/7EUzyWLcED— TESLARATI (@Teslarati) July 15, 2025

Deliveries are currently scheduled for the third quarter, and it will be interesting to see how many units they can sell in the market at this price point.

The price includes tariffs and additional fees that are applied by the Indian government, which has aimed to work with foreign automakers to come to terms on lower duties that increase vehicle cost.

Tesla Model Y seen testing under wraps in India ahead of launch

There is a chance that these duties will be removed, which would create a more stable and affordable pricing model for Tesla in the future. President Trump and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi continue to iron out those details.

Maharashtra Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis said to reporters outside the company’s new outlet in the region (via Reuters):

“In the future, we wish to see R&D and manufacturing done in India, and I am sure at an appropriate stage, Tesla will think about it.”

It appears to be eerily similar to the same “game of chicken” Tesla played with Indian government officials for the past few years. Tesla has always wanted to enter India, but was unable to do so due to these import duties.

India wanted Tesla to commit to building a Gigafactory in the country, but Tesla wanted to test demand first.

It seems this could be that demand test, and the duties are going to have a significant impact on what demand will actually be.

Elon Musk

Tesla ups Robotaxi fare price to another comical figure with service area expansion

Tesla upped its fare price for a Robotaxi ride from $4.20 to, you guessed it, $6.90.

Tesla has upped its fare price for the Robotaxi platform in Austin for the first time since its launch on June 22. The increase came on the same day that Tesla expanded its Service Area for the Robotaxi ride-hailing service, offering rides to a broader portion of the city.

The price is up from $4.20, a figure that many Tesla fans will find amusing, considering CEO Elon Musk has used that number, as well as ’69,’ as a light-hearted attempt at comedy over the past several years.

Musk confirmed yesterday that Tesla would up the price per ride from that $4.20 point to $6.90. Are we really surprised that is what the company decided on, as the expansion of the Service Area also took effect on Monday?

But the price is now a princely $6.90, as foretold in the prophecy 😂

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) July 14, 2025

The Service Area expansion was also somewhat of a joke too, especially considering the shape of the new region where the driverless service can travel.

I wrote yesterday about how it might be funny, but in reality, it is more of a message to competitors that Tesla can expand in Austin wherever it wants at any time.

Tesla’s Robotaxi expansion wasn’t a joke, it was a warning to competitors

It was only a matter of time before the Robotaxi platform would subject riders to a higher, flat fee for a ride. This is primarily due to two reasons: the size of the access program is increasing, and, more importantly, the service area is expanding in size.

Tesla has already surpassed Waymo in Austin in terms of its service area, which is roughly five square miles larger. Waymo launched driverless rides to the public back in March, while Tesla’s just became available to a small group in June. Tesla has already expanded it, allowing new members to hail a ride from a driverless Model Y nearly every day.

The Robotaxi app is also becoming more robust as Tesla is adding new features with updates. It has already been updated on two occasions, with the most recent improvements being rolled out yesterday.

Tesla updates Robotaxi app with several big changes, including wider service area

News

Tesla Model Y and Model 3 dominate U.S. EV sales despite headwinds

Tesla’s two mainstream vehicles accounted for more than 40% of all EVs sold in the United States in Q2 2025.

Tesla’s Model Y and Model 3 remained the top-selling electric vehicles in the U.S. during Q2 2025, even as the broader EV market dipped 6.3% year-over-year.

The Model Y logged 86,120 units sold, followed by the Model 3 at 48,803. This means that Tesla’s two mainstream vehicles accounted for 43% of all EVs sold in the United States during the second quarter, as per data from Cox Automotive.

Tesla leads amid tax credit uncertainty and a tough first half

Tesla’s performance in Q2 is notable given a series of hurdles earlier in the year. The company temporarily paused Model Y deliveries in Q1 as it transitioned to the production of the new Model Y, and its retail presence was hit by protests and vandalism tied to political backlash against CEO Elon Musk. The fallout carried into Q2, yet Tesla’s two mass-market vehicles still outsold the next eight EVs combined.

Q2 marked just the third-ever YoY decline in quarterly EV sales, totaling 310,839 units. Electric vehicle sales, however, were still up 4.9% from Q1 and reached a record 607,089 units in the first half of 2025. Analysts also expect a surge in Q3 as buyers rush to qualify for federal EV tax credits before they expire on October 1, Cox Automotive noted in a post.

Legacy rivals gain ground, but Tesla holds its commanding lead

General Motors more than doubled its EV volume in the first half of 2025, selling over 78,000 units and boosting its EV market share to 12.9%. Chevrolet became the second-best-selling EV brand, pushing GM past Ford and Hyundai. Tesla, however, still retained a commanding 44.7% electric vehicle market share despite a 12% drop in in Q2 revenue, following a decline of almost 9% in Q1.

Incentives reached record highs in Q2, averaging 14.8% of transaction prices, roughly $8,500 per vehicle. As government support winds down, the used EV market is also gaining momentum, with over 100,000 used EVs sold in Q2.

Q2 2025 Kelley Blue Book EV Sales Report by Simon Alvarez on Scribd

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoTesla debuts hands-free Grok AI with update 2025.26: What you need to know

-

Elon Musk1 week ago

Elon Musk1 week agoElon Musk confirms Grok 4 launch on July 9 with livestream event

-

Elon Musk5 days ago

Elon Musk5 days agoxAI launches Grok 4 with new $300/month SuperGrok Heavy subscription

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoTesla Model 3 ranks as the safest new car in Europe for 2025, per Euro NCAP tests

-

Elon Musk2 weeks ago

Elon Musk2 weeks agoxAI’s Memphis data center receives air permit despite community criticism

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoTesla begins Robotaxi certification push in Arizona: report

-

Elon Musk2 weeks ago

Elon Musk2 weeks agoTesla reveals it is using AI to make factories more sustainable: here’s how

-

Elon Musk2 weeks ago

Elon Musk2 weeks agoTesla scrambles after Musk sidekick exit, CEO takes over sales