News

SpaceX vs. Blue Origin: The bickering titans of new space

In the past three years, SpaceX has made incredible progress in their program of reusability. In the practice’s first year, the young space company led by serial tech entrepreneur Elon Musk has performed three successful commercial reuses of Falcon 9 boosters in approximately eight months, and has at least two more reused flights scheduled before 2017 is out. Blue Origin, headed and funded by Jeff Bezos of Amazon fame, is perhaps most famous for its supreme confidence, best illustrated by Bezos offhandedly welcoming SpaceX “to the club” after the company first recovered the booster stage of its Falcon 9 rocket in 2015.

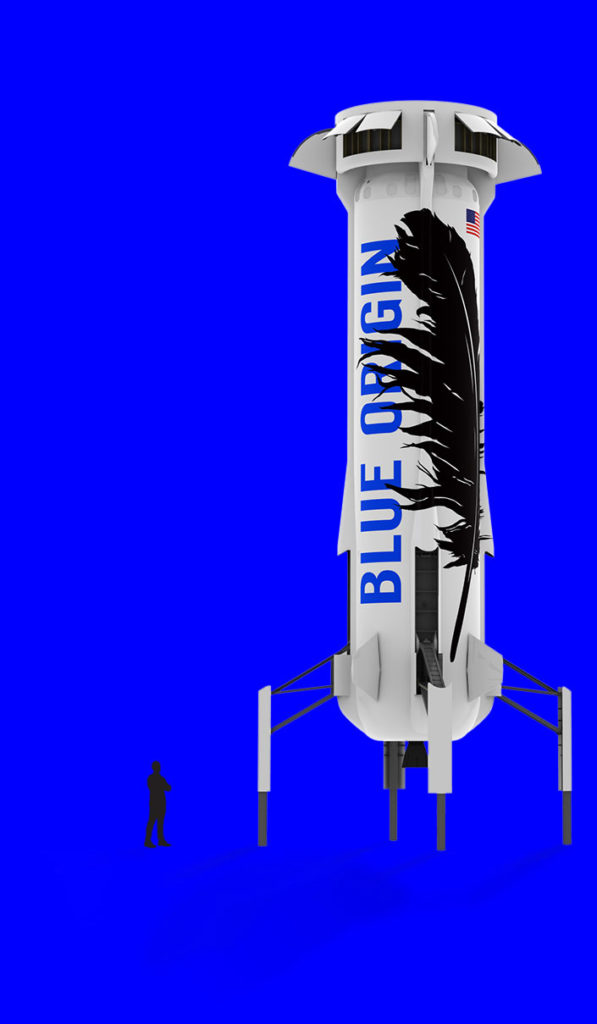

Blue Origin began in the early 2000s as a pet project of Bezos, a long-time fan of spaceflight and proponent of developing economies in space. After more than a decade of persistent development and increasingly complex testbeds, Blue Origin began a multi-year program of test flights with its small New Shepard launch vehicle. Designed to eventually launch tourists to the veritable edge of Earth’s atmosphere in a capsule atop it, New Shepard began its test flights in 2015 and after one partial failure, has completed five successful flights in a row. The space tourism company has subtly and not-so-subtly belittled SpaceX’s accomplishments over the last several years, and has engendered a fair bit of hostility towards it as a result.

Admittedly, CEO Elon Musk nurtured high expectations for the consequences of reuse, and has frequently discussed SpaceX’s ambition to reduce the cost of access to orbit by a factor of 10 to 100. However, after several reuses, it is clear that costs have decreased no more than 10-20%. What gives?

Well, Musk’s many comments on magnitudes of cost reduction were clearly premised upon rapid and complete reuse of both stages of Falcon 9, best evidenced by a concept video the company released in 2011.

The reality was considerably harder and Musk clearly underestimated the difficulty of second stage reuse, something he himself has admitted. COO Gwynne Shotwell was interviewed earlier this summer and discussed SpaceX’s updated approach to complete reusability, and acknowledged that second stage reuse was no longer a real priority, although the company will likely attempt second stage recovery as a validation of future technologies. Instead of pursuing the development of a completely reusable Falcon 9, SpaceX is instead pushing ahead with the development of a much larger rocket, BFR. BFR being designed to enable the sustainable colonization of space by realizing Musk’s original ambition of magnitudes-cheaper orbital launch capabilities.

Competition on the horizon?

Meanwhile, SpaceX’s only near-term competitor interested in serious reuse has made gradual progress over the last several years, accelerating its pace of development more recently. Blue Origin’s second New Shepard vehicle, designed to serve the suborbital space tourism industry, conducted an impressive five successful launches and landings over the course of 2016 before being summarily retired. NS2’s antecedent suffered a failure while attempting its first landing and was destroyed in 2015, but Blue learned quickly from the issues of Shepard 1 and has already shipped New Shepard 3 to its suborbital launch facilities near Van Horn, Texas. While NS3 is aiming for an inaugural flight later this year, NS4 is under construction in Kent, Washington and could support Blue’s first crewed suborbital launches in 2018.

More significant waves were made with an announcement in 2016 that Blue was pursuing development of a partially reusable orbital-class launch vehicle, the massive New Glenn. On paper, New Glenn is quite a bit larger than even SpaceX’s Falcon 9, and appears to likely be more capable than the company’s “world’s most powerful rocket” while completely recovering its boost stage. In a completed, manufactured, and demonstrably reliable form, New Glenn would be an extraordinarily impressive and capable launch vehicle that could undoubtedly catapult Blue Origin into position of true competition with SpaceX’s reusability efforts.

- The New Shepard booster. (Blue Origin)

- Blue Origin’s New Shepard capsule could carry passengers as high as 100km in 2018. (Blue Origin)

- A render of Blue Origin’s larger New Glenn vehicle. (Blue Origin)

However, while Blue Origin executives brag about “operational reusability” and tastelessly lampoon efforts that “decided to slap some legs on [to] see if [they] could land it”, the unmentioned company implicated in those barbs has begun to routintely and commercially reuse orbital-class boosters five times the size of Blue’s suborbital testbed, New Shepard.

Apples to oranges

The only point at which Blue Origin poses a risk to SpaceX’s business can be found in a comparison of funding sources. SpaceX first successes (and failures) were funded out of Elon Musk’s own pocket, but nearly all of the funding that followed was won through competitive government contracts and rounds of private investment. To put it more simply, SpaceX is a business that must balance costs and returns, while Blue Origin is funded exclusively out of billionaire CEO Jeff Bezos’ pocket.

As a result of being completely privately funded, Bezos’ deep pockets could render Blue more flexible than SpaceX when pricing launches. If Blue chooses to aggressively price New Glenn by accounting for booster reusability, it could pose a threat to SpaceX’s own business strategy. If SpaceX is unable to recoup its investment in reusability before New Glenn is regularly conducting multiple commercial missions per year, likely no earlier than 2021 or 2022, SpaceX’s Falcon 9 pricing could be rendered distinctly noncompetitive.

However, this concern seems almost entirely misplaced. SpaceX has half a decade of experience mass-producing orbital-class (reusable) rockets, (reusable) fairings, and propulsion systems, whereas Blue Origin at best has minimal experience manufacturing a handful of suborbital vehicles over a period of a few years. Blue has a respectable amount of experience with their BE-3 hydrolox propulsion system, and that will likely transfer over to the BE-3U vacuum variant to be used for New Glenn’s third stage. The large methalox rocket engine (BE-4) that will power New Glenn’s first stage also conducted its first-ever hot-fire just weeks ago, a major milestone in propulsion development but also a reminder that BE-4 has an exhaustive regime of engineering verification and flight qualification testing ahead of it.

First hotfire of our BE-4 engine is a success #GradatimFerociter pic.twitter.com/xuotdzfDjF

— Blue Origin (@blueorigin) October 19, 2017

Perhaps more importantly, the company’s relative success with New Shepard’s launch, recovery, and reuse has not and cannot move beyond small suborbital hops, and thus cannot provide the experience at the level of orbital rocketry. New Shepard is admittedly capable of reaching an altitude of 100km, but the suborbital vehicle’s flight regime does not require it to travel beyond Mach 4 (~1300 m/s). The first stage of Falcon 9, however, is approximately four times as tall and three times the mass of New Shepard, and boosters attempting recovery during geostationary missions routinely reach almost twice the velocity of New Shepard, entering the thicker atmosphere at more than 2300 m/s (1500-1800 m/s for LEO missions). Falcon 9’s larger mass and velocity translates into intense reentry heating and aerodynamic forces, best demonstrated by the glowing aluminum grid fins that can often be seen in SpaceX’s live coverage of booster recovery. Blue Origin’s New Glenn concept is extremely impressive on paper, but the company will have to pull off an extraordinary leap of technological maturation to move directly from suborbital single-stage hops to multi-stage orbital rocketry. Blue’s accomplishments with New Shepard are nothing to scoff at, but they are a far cry from routine orbital launch services.

SpaceX’s future fast approaches

Translating back to the new establishment, Falcon 9 will likely remain SpaceX’s workhorse rocket for some five or more years, at least until BFR can prove itself to be a reliable and affordable replacement. This change in focus, combined with the downsides of second stage recovery and reuse on a Falcon 9-sized vehicle, means that SpaceX will ‘only’ end up operationally reusing first stages and fairings from the vehicle. The second stage accounts for approximately 20-30% of Falcon 9’s total cost, suggesting that rapid and complete reuse of the fairing and first stage could more than halve its ~$62 million price. Yet this too ignores another mundane fact of corporate life SpaceX must face. Its executives, Musk included, have lately expressed a desire to at least partially recoup the ~$1 billion that was invested to develop reuse. Assuming a partial 10% reduction in cost to reuse customers and profit margins of 50% with rapid and total reuse of the first stage and fairing, 20 to 30 commercial reuses would recoup most or all of SpaceX’s reusability investment.

Musk recently revealed that SpaceX is aiming to complete 30 launches in 2018, and that figure will likely continue to grow in 2019, assuming no major anomalies occur. Manufacturing will rapidly become the main choke point for increased launch cadence, suggesting that drastically higher cadences will largely depend upon first stage reuse with minimal refurbishment, which just so happens to be the goal of the Falcon 9’s upcoming Block 5 iteration. Even if the modifications only manage a handful of launches without refurbishment, rather than the ten flights being pursued, each additional flight without maintenance will effectively multiply SpaceX’s manufacturing capabilities. More bluntly: ten Falcon 9s capable of five reflights could do the same job of 50 brand new rockets with 1/5th of the manufacturing backend.

- BulgariaSat-1 was successfully launched 48 hours before Iridium-2, and marked the second or three successful, commercial reuses of an orbital rocket. (SpaceX)

- SpaceX’s Hawthorne factory routinely churns out one to two complete Falcon 9s every month. (SpaceX)

- Falcon 9 B1040 returns to LZ-1 after the launch of the USAF’s X-37B spaceplane. (SpaceX)

Assuming that upcoming reuses proceed without significant failures and Falcon 9 Block 5 subsumes all manufacturing sometime in 2018 or 2019, it is entirely possible that SpaceX will undergo an extraordinarily rapid phase change from expendability to reusability. Mirroring 2017, we can imagine that SpaceX’s Hawthorne factory will continue to churn out at least 10 to 20 Block 5 Falcon 9s over the course of 2018. Assuming 5 to 10 maintenance-free reuses and a lifespan of as many as 100 flights with intermittent refurb, a single year of manufacturing could provide SpaceX with enough first stages to launch anywhere from 50 to 2000 missions. The reality will inevitably find itself somewhere between those extremely pessimistic and optimistic bookends, and they of course do not account for fairings, second stages, or expendable flights.

If we assume that the proportional cost of Falcon 9’s many components very roughly approximates the amount of manufacturing backend needed to produce them, downsizing Falcon 9 booster production by a factor of two or more could free a huge fraction of SpaceX’s workforce and floor space to be repurposed for fairing and second stage production, as well as the company’s Mars efforts. Such a phase change would also free up a considerable fraction of the capital SpaceX continually invests in its manufacturing infrastructure and workforce, capital that could then be used to ready SpaceX’s facilities for production and testing of its Mars-focused BFR and BFS.

“Gradatim ferociter”

It cannot be overstated that the speculation in this article is speculation. Nevertheless, it is speculation built on real information provided over the years by SpaceX’s own executives. Rough estimates like this offer a glimpse into a new launch industry paradigm that could be only a year or two away and could allow SpaceX to begin aggressively pursuing its goal of enabling a sustainable human presence on Mars and throughout the Solar System.

Blue Origin’s future endeavors shine on paper and their goal of enabling millions to work and live space are admirable, but the years between the present and a future of routine orbital missions for the company may not be kind. The engineering hurdles that litter the path to orbital rocketry are unforgiving and can only be exacerbated by blind overconfidence, a lesson that is often only learned the hard way. Blue Origin’s proud motto “Gradatim ferociter” roughly translates to “Step by step, ferociously.” One can only hope that some level of humility and sobriety might temper that ferocity before customers entrust New Glenn with their infrastructural foundations and passengers entrust New Shepard with their lives.

News

Lucid unveils Lunar Robotaxi in bid to challenge Tesla’s Cybercab in the autonomous ride hailing race

Lucid’s Lunar robotaxi is gunning for Tesla’s Cybercab in the autonomous ride hailing race

![Lucid Lunar robotaxi concept [Credit: Rendering by TESLARATI]](https://www.teslarati.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/03/lucid-lunar-robotaxi-concept-teslarati-rendering.jpg)

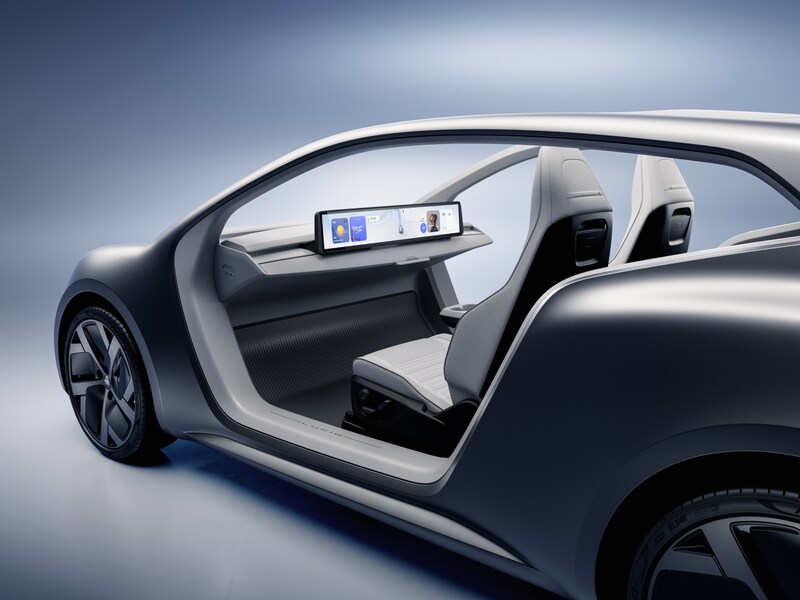

Lucid Group pulled back the curtain on its purpose-built autonomous robotaxi platform dubbed the Lunar Concept. Announced at its New York investor day event, Lunar is arguably the company’s most ambitious concept yet, and a direct line of sight toward the autonomous ride haling market that Tesla looks to control.

At Lucid Investor Day 2026, the company introduced Lunar, a purpose-built robotaxi concept based on the Midsize platform.

A comparison to Tesla’s Cybercab is unavoidable. The concept of a Tesla robotaxi was first introduced by Elon Musk back in April 2019 during an event dubbed “Autonomy Day,” where he envisioned a network of self-driving Tesla vehicles transporting passengers while not in use by their owners. That vision took another major step in October 2024 when, Musk unveiled the Cybercab at the Tesla “We, Robot” event held at Warner Bros. Studios in Burbank, California, where 20 concept Cybercabs autonomously drove around the studio lot giving rides to attendees.

Fast forward to today, and Tesla’s ambitions are finally materializing, but not without friction. As we recently reported, the Cybercab is being spotted with increasing frequency on public roads and across the grounds of Gigafactory Texas, suggesting that the company’s road testing and validation program is ramping meaningfully ahead of mass production. Tesla already operates a small scale robotaxi service in Austin using supervised Model Ys, but the Cybercab is designed from the ground up for high-volume, low-cost production, with Musk stating an eventual goal of producing one vehicle every 10 seconds.

At Lucid Investor Day 2026, the company introduced Lunar, a purpose-built robotaxi concept based on the Midsize platform.

Into this landscape steps Lucid’s Lunar. Built on the company’s all-new Midsize EV platform, which will also underpin consumer SUVs starting below $50,000. The Lunar mirrors the Cybercab’s core philosophy of having two seats, no driver controls, and a focus on fleet economics. The platform introduces Lucid’s redesigned Atlas electric drive unit, engineered to be smaller, lighter, and cheaper to manufacture at scale.

Unlike Tesla’s strategy of building its own ride hailing network from scratch, Lucid is partnering with Uber. The companies are said to be in advanced discussions to deploy Midsize platform vehicles at large scale, with Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi publicly backing Lucid’s engineering credentials and autonomous-ready architecture.

In the investor day event, Lucid also outlined a recurring software revenue model, with an in-vehicle AI assistant and monthly autonomous driving subscriptions priced between $69 and $199. This can be seen as a nod to the software revenue stream that Tesla has long championed with its Full Self-Driving subscription.

Tesla’s Cybercab is targeting a price point below $30k and with operating costs as low as 20 cents per mile. But with regulatory hurdles still ahead, the window for competition is open. Lucid’s Lunar may not have a launch date yet, but it arrives at a pivotal moment, and when the robotaxi race is no longer viewed as hypothetical. Rather, every serious EV player needs to come to bat on the same plate that Tesla has had countless practice swings on over the last seven years.

Elon Musk

Brazil Supreme Court orders Elon Musk and X investigation closed

The decision was issued by Supreme Court Justice Alexandre de Moraes following a recommendation from Brazil’s Prosecutor-General Paulo Gonet.

Brazil’s Supreme Federal Court has ordered the closure of an investigation involving Elon Musk and social media platform X. The inquiry had been pending for about two years and examined whether the platform was used to coordinate attacks against members of the judiciary.

The decision was issued by Supreme Court Justice Alexandre de Moraes following a recommendation from Brazil’s Prosecutor-General Paulo Gonet.

According to a report from Agencia Brasil, the investigation conducted by the Federal Police did not find evidence that X deliberately attempted to attack the judiciary or circumvent court orders.

Prosecutor-General Paulo Gonet concluded that the irregularities identified during the probe did not indicate fraudulent intent.

Justice Moraes accepted the prosecutor’s recommendation and ruled that the investigation should be closed. Under the ruling, the case will remain closed unless new evidence emerges.

The inquiry stemmed from concerns that content on X may have enabled online attacks against Supreme Court justices or violated rulings requiring the suspension of certain accounts under investigation.

Justice Moraes had previously taken several enforcement actions related to the platform during the broader dispute involving social media regulation in Brazil.

These included ordering a nationwide block of the platform, freezing Starlink accounts, and imposing fines on X totaling about $5.2 million. Authorities also froze financial assets linked to X and SpaceX through Starlink to collect unpaid penalties and seized roughly $3.3 million from the companies’ accounts.

Moraes also imposed daily fines of up to R$5 million, about $920,000, for alleged evasion of the X ban and established penalties of R$50,000 per day for VPN users who attempted to bypass the restriction.

Brazil remains an important market for X, with roughly 17 million users, making it one of the platform’s larger user bases globally.

The country is also a major market for Starlink, SpaceX’s satellite internet service, which has surpassed one million subscribers in Brazil.

Elon Musk

FCC chair criticizes Amazon over opposition to SpaceX satellite plan

Carr made the remarks in a post on social media platform X.

U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Chairman Brendan Carr criticized Amazon after the company opposed SpaceX’s proposal to launch a large satellite constellation that could function as an orbital data center network.

Carr made the remarks in a post on social media platform X.

Amazon recently urged the FCC to reject SpaceX’s application to deploy a constellation of up to 1 million low Earth orbit satellites that could serve as artificial intelligence data centers in space.

The company described the proposal as a “lofty ambition rather than a real plan,” arguing that SpaceX had not provided sufficient details about how the system would operate.

Carr responded by pointing to Amazon’s own satellite deployment progress.

“Amazon should focus on the fact that it will fall roughly 1,000 satellites short of meeting its upcoming deployment milestone, rather than spending their time and resources filing petitions against companies that are putting thousands of satellites in orbit,” Carr wrote on X.

Amazon has declined to comment on the statement.

Amazon has been working to deploy its Project Kuiper satellite network, which is intended to compete with SpaceX’s Starlink service. The company has invested more than $10 billion in the program and has launched more than 200 satellites since April of last year.

Amazon has also asked the FCC for a 24-month extension, until July 2028, to meet a requirement to deploy roughly 1,600 satellites by July 2026, as noted in a CNBC report.

SpaceX’s Starlink network currently has nearly 10,000 satellites in orbit and serves roughly 10 million customers. The FCC has also authorized SpaceX to deploy 7,500 additional satellites as the company continues expanding its global satellite internet network.

![Lucid Lunar robotaxi concept [Credit: Rendering by TESLARATI]](https://www.teslarati.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/03/lucid-lunar-robotaxi-concept-teslarati-rendering-80x80.jpg)