News

SpaceX’s path to refueling Starships in space is clearer than it seems

Perhaps the single biggest mystery of SpaceX’s Starship program is how exactly the company plans to refuel the largest spacecraft ever built after they reach orbit.

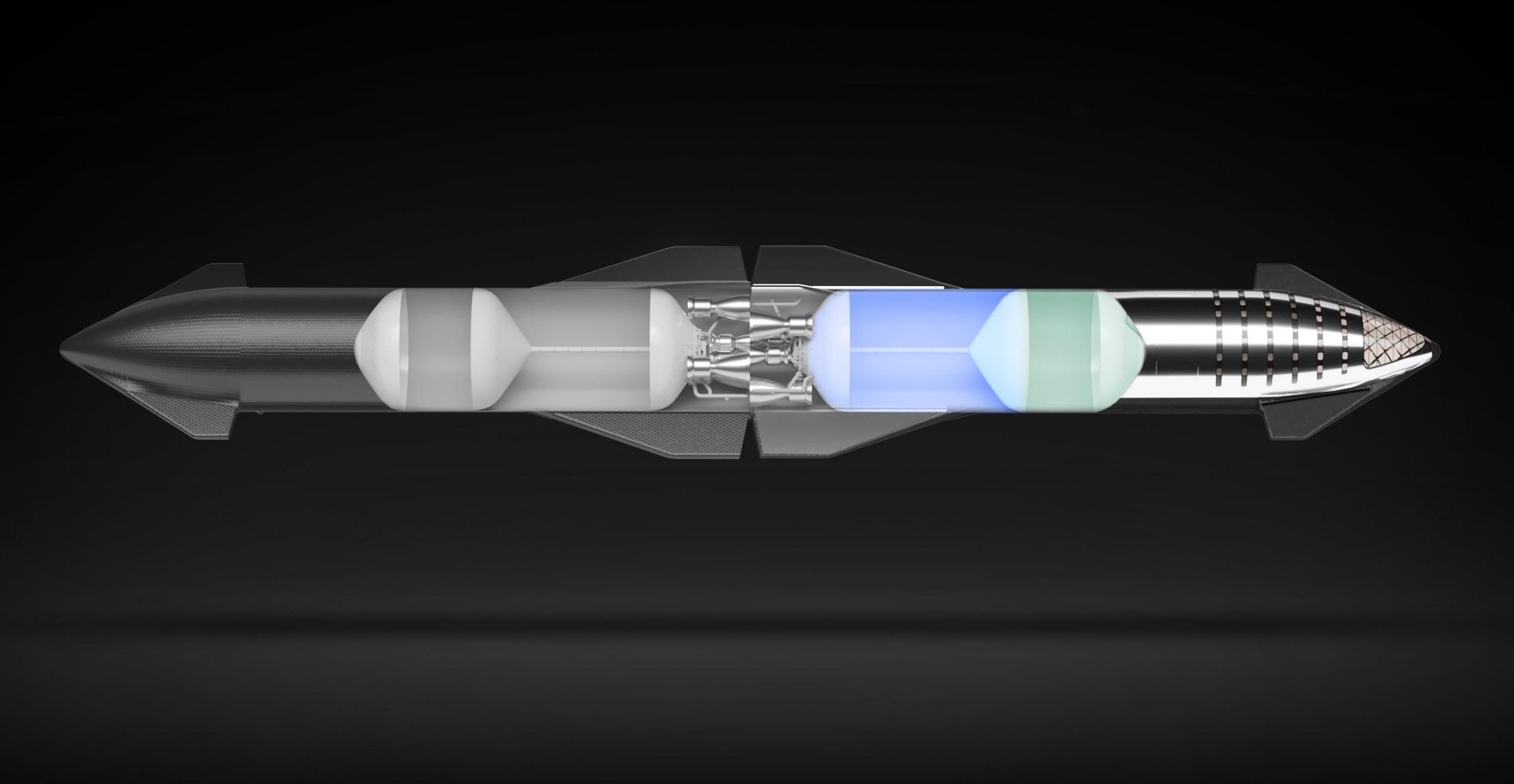

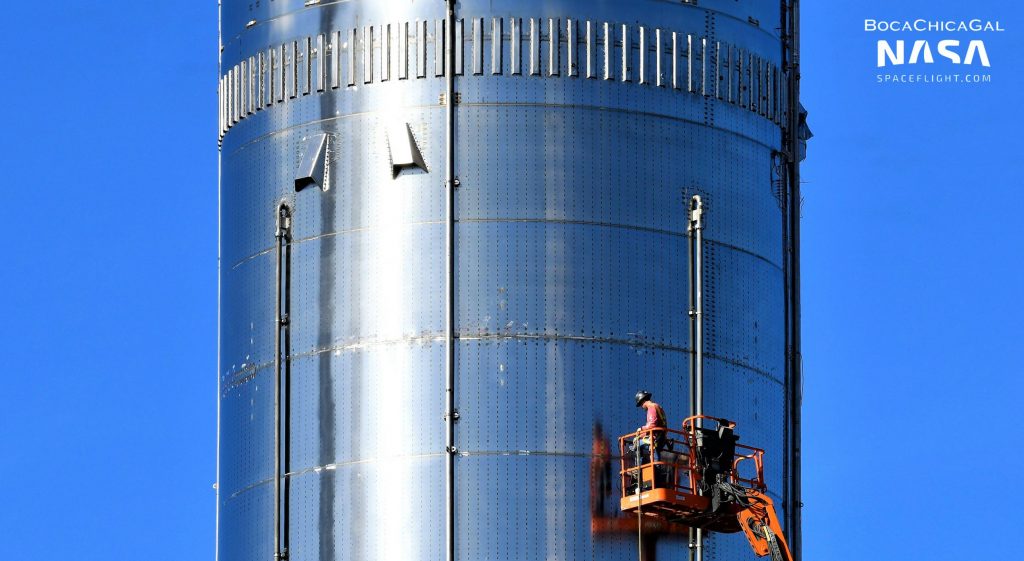

First revealed in September 2016 as the Interplanetary Transport System (ITS), SpaceX has radically redesigned its next-generation rocket several times over the last half-decade. Several crucial aspects have nevertheless persisted. Five years later, Starship (formerly ITS and BFR) is still a two-stage rocket powered by Raptor engines that burn a fuel-rich mixture of liquid methane (LCH4) and liquid oxygen (LOx). Despite being significantly scaled back from ITS, Starship will be about the same height (120 m or 390 ft) and is still on track to be the tallest, heaviest, and most powerful rocket ever launched by a large margin.

Building off of years of growing expertise from dozens of Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy launches, the most important fundamental design goal of Starship is full and rapid reusability – propellant being the only thing intentionally ‘expended’ during launches. However, like BFR and ITS before it, the overarching purpose of Starship is to support SpaceX’s founding goal of making humanity multiplanetary and building a self-sustaining city on Mars. For Starship to have even a chance of accomplishing that monumental feat, SpaceX will not only have to build the most easily and rapidly reusable rocket and spacecraft in history, but it will also have to master orbital refueling.

The reuse/refuel equation

In the context of SpaceX’s goals of expanding humanity to Mars, a mastery of reusability and orbital refueling are mutually inclusive. Without both, neither alone will enable the creation of a sustainable city on Mars. A Starship launch system that can be fully reused on a weekly or even daily basis but can’t be rapidly and easily refueled in space simply doesn’t have the performance needed to affordably build, supply, and populate a city on another planet (or Moon). A Starship launch system that can be easily refueled but is not rapidly and fully reusable could allow for some degree of interplanetary transport and the creation of a minimal human outpost on Mars, but it would probably be one or two magnitudes more difficult, risky, and expensive to operate and would require a huge fleet of ships and boosters from the start.

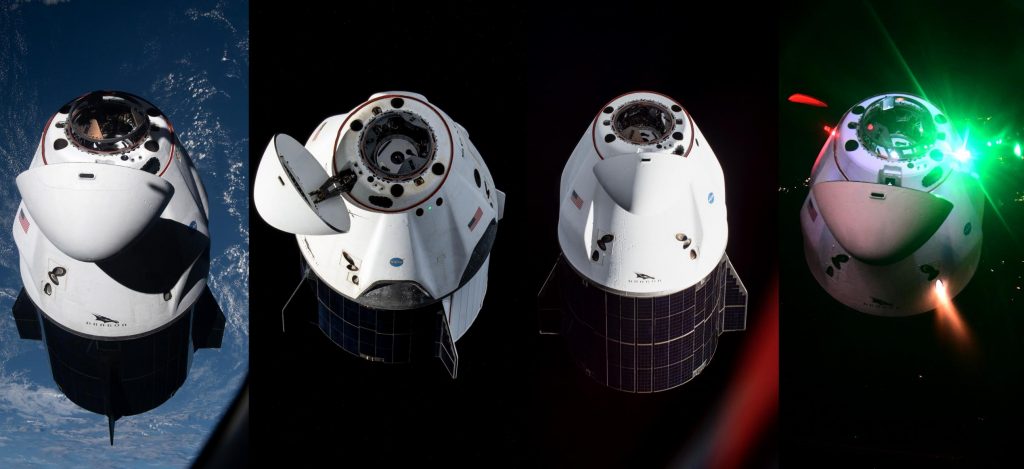

The question of how SpaceX will make Starship the world’s most rapidly, fully, and cheaply reusable rocket is a hard one, but it’s not all that difficult to extrapolate from where the company is today. Currently, the turnaround record (time between two flights) for Falcon boosters is two launches in less than four weeks (27 days). SpaceX’s orbital-class reuse is also making strides and the company recently flew the same orbital Crew Dragon capsule twice in just 137 days (less than five months) – fast approaching turnarounds similar to NASA’s Space Shuttle average, the only other reusable orbital spacecraft in history.

While Dragon and Falcon 9 are far smaller than Starship and Super Heavy, Dragon is only partially reusable and requires significant refurbishment after recovery and Falcon 9 boosters are fairly complex. Starship, on the other hand, should effectively serve as a fully reusable all-in-one Falcon upper stage, Dragon capsule, Dragon trunk, and fairing, making it far more complex but potentially far more reusable. To an extent, Super Heavy should also be mechanically simpler than Falcon boosters (no deployable legs or fins; no structural composite-metal joints; no dedicated maneuvering thrusters) and its clean-burning Raptor engines should be easier to reuse than Falcon’s Merlins. Put simply, there are precedents set and evidence provided by Falcon rockets and NASA’s Space Shuttle that suggest SpaceX will be able to solve the reusability half of the equation.

What about refueling?

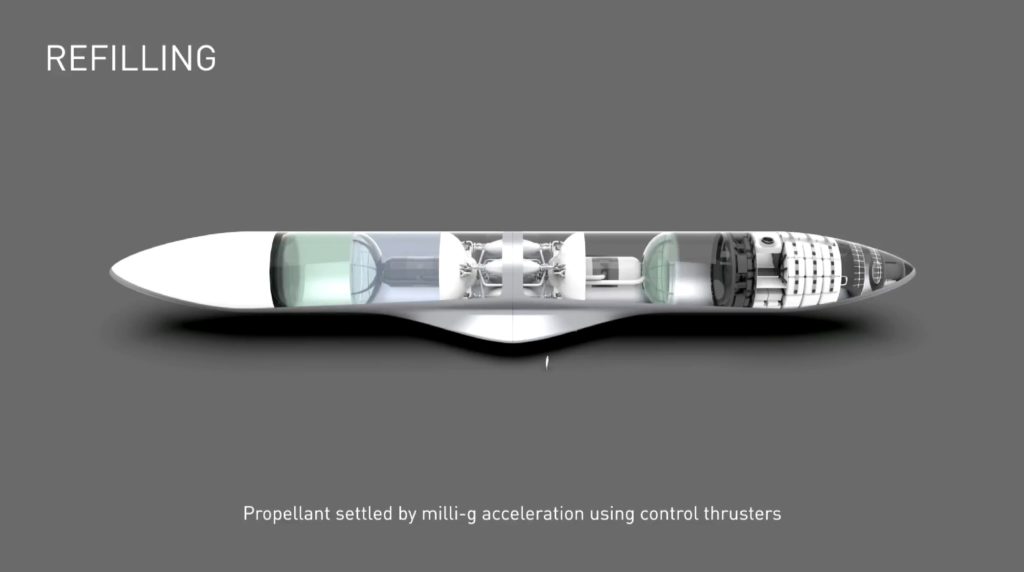

The other half of that equation, however, could not be more different. The sum total of SpaceX’s official discussions of orbital refueling can be summed up in a sentence included verbatim in CEO Elon Musk’s 2017, 2018, and 2019 Starship presentations: “propellant settled by milli G acceleration using control thrusters.”

On the face of it, that simple phrase doesn’t reveal much. However, with a few grains of salt, hints from what the company’s CEO has and hasn’t said, and context from the history of research into orbital propellant transfer, it’s possible to paint a fairly detailed picture of the exact mechanisms SpaceX will likely use to refill Starships in space. The cornerstone, somewhat ironically, is a 2006 paper – written by seven Lockheed Martin employees and a NASA engineer – titled “Settled Cryogenic Propellant Transfer.” Aside from the obvious corollaries just from the title alone, the paper focuses on what the authors argue is the simplest possible route to large-scale orbital propellant transfer.

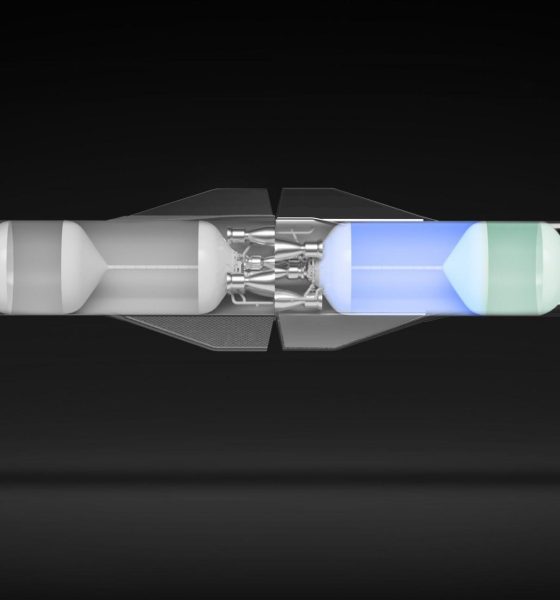

In orbit, under microgravity conditions, the propellant inside a spacecraft’s tanks is effectively detached from the structure. If a spacecraft applies thrust, that propellant will stay still until it splashes against its tank walls – the most basic Newtonian principle that objects at rest tend to stay at rest. If, say, a spacecraft thrusts in one direction and opens a hatch or valve on the tank in the opposite direction of that thrust, the propellant inside it – attempting to stay at rest – will naturally escape out of that opening. Thus, if a spacecraft in need of fuel docks with a tanker, their tanks are connected and opened, and the tanker attempts to accelerate away from the receiving ship, the propellant in the tanker’s tanks will effectively be pushed into the second ship as it tries to stay at rest.

The principles behind such a ‘settled propellant transfer’ are fairly simple and intuitive. The crucial question is how much acceleration the process requires and how expensive that continuous acceleration ends up being. According to Kutter et al’s 2006 paper, the answer is surprising: assuming a 100 metric ton (~220,000 lb) spacecraft pair accelerates at 0.0001G (one ten-thousandth of Earth gravity) to transfer propellant, they would need to consume just 45 kg (100 lb) of hydrogen and oxygen propellant per hour to maintain that acceleration.

In the most extreme hypothetical refueling scenario (i.e. a completely full tanker refueling a ship with a full cargo bay), two docked Starships would weigh closer to 1600 tons (~3.5M lb) and the “Milli G” acceleration SpaceX has repeatedly mentioned in presentation slides would be ten times greater than the maximum acceleration analyzed by Kutter et al. Still, according to their paper, that propellant cost scales linearly both with the required acceleration and with the mass of the system. Roughly speaking, using the same assumptions, that means that the thrusting Starship would theoretically consume just over 7 tons (half a percent) of its methane and oxygen propellant per hour to maintain milli-G acceleration.

With large enough pipes (on the order of 20-50 cm or 8-20 in) connecting each Starship’s tanks, SpaceX should have no trouble transferring 1000+ tons of propellant in a handful of hours. Ultimately, that means that settled propellant transfer even at the scale of Starship should incur a performance ‘tax’ of no more than 20-50 tons of propellant per refueling. All transfers leading up to the worst-case 1600-ton scenario should also be substantially more efficient. Overall, that means that fully refueling an orbiting Starship or depot with ~1200 tons of propellant – requiring anywhere from 8 to 14+ tanker launches – should be surprisingly efficient, with perhaps 80% or more of the propellant launched remaining usable by the end of the process.

A step further, Kutter et al note the amount of acceleration required is so small that a hypothetical spacecraft could potentially use ullage gas vents to achieve it, meaning that custom-designed settling thrusters might not even be needed. Coincidentally or not, SpaceX (or CEO Elon Musk) has recently decided to use strategically located ullage vents to replace purpose-built maneuvering thrusters on Starship’s Super Heavy booster. If SpaceX adds similar capabilities to Starship, it’s quite possible that the combination of cryogenic propellant naturally boiling into gas as it warms and the ullage vents used to relieve that added pressure could produce enough thrust to transfer large volumes of propellant.

Last but not least, writing more than a decade and a half ago, the only technological barrier Kutter et al could foresee to large-scale settled propellant transfer wasn’t even related to refueling but, rather, to the ability to autonomously rendezvous and dock in orbit. In 2006, while Russia was already routinely using autonomous docking and rendezvous technology on its Soyuz and Progress spacecraft, the US had never demonstrated the technology on its own. Jump to today and SpaceX Dragon spacecraft have autonomously rendezvoused with the International Space Station twenty seven times in nine years and completed ten autonomous dockings – all without issue – since 2019.

Even though SpaceX and its executives have never detailed their approach to refueling (or refilling, per Musk’s preferred term) Starships in space, there is a clear path established by decades of NASA and industry research. What little evidence is available suggests that that path is the same one SpaceX has chosen to travel. Ultimately, the key takeaway from that research and SpaceX’s apparent use of it should be this: while a relatively inefficient process, SpaceX has effectively already solved the last remaining technical hurdle for settled propellant transfer and should be able to easily refuel Starships in orbit with little to no major development required.

There’s a good chance that minor to moderate problems will be discovered and need to be solved once SpaceX begins to test refueling in orbit but crucially, there are no obvious showstoppers standing between SpaceX and the start of those flight tests. Aside from the obvious (preparing a new rocket for its first flight tests), the only major refueling problem SpaceX arguably needs to solve is the umbilical ports and docking mechanisms that will enable propellant transfer. SpaceX will also need to settle on a location for those ports/mechanisms and decide whether to implement ullage vent ‘thrusters’, cold gas thrusters like those on Falcon and current Starship prototypes, or more efficient hot-gas thrusters derived from Raptors. At the end of the day, though, those are all solved problems and just a matter of complex but routine systems engineering that SpaceX is an expert at.

News

Tesla adds awesome new driving feature to Model Y

Tesla is rolling out a new “Comfort Braking” feature with Software Update 2026.8. The feature is exclusive to the new Model Y, and is currently unavailable for any other vehicle in the Tesla lineup.

Tesla is adding an awesome new driving feature to Model Y vehicles, effective on Juniper-updated models considered model year 2026 or newer.

Tesla is rolling out a new “Comfort Braking” feature with Software Update 2026.8. The feature is exclusive to the new Model Y, and is currently unavailable for any other vehicle in the Tesla lineup.

Tesla writes in the release notes for the feature:

“Your Tesla now provides a smoother feel as you come to a complete stop during routine braking.”

🚨 Tesla has added a new “Comfort Braking” update with 2026.8

“Your Tesla provides a smoother feel as you come to a complete stop during routine braking.” https://t.co/afqCpBSVeA pic.twitter.com/C6MRmzfzls

— TESLARATI (@Teslarati) March 13, 2026

Interestingly, we’re not too sure what catalyzed Tesla to try to improve braking smoothness, because it hasn’t seemed overly abrupt or rough from my perspective. Although the brake pedal in my Model Y is rarely used due to Regenerative Braking, it seems Tesla wanted to try to make the ride comfort even smoother for owners.

There is always room for improvement, though, and it seems that there is a way to make braking smoother for passengers while the vehicle is coming to a stop.

This is far from the first time Tesla has attempted to improve its ride comfort through Over-the-Air updates, as it has rolled out updates to improve regenerative braking performance, handling while using Full Self-Driving, improvements to Steer-by-Wire to Cybertruck, and even recent releases that have combatted Active Road Noise.

Tesla holds a unique ability to change the functionality of its vehicles through software updates, which have come in handy for many things, including remedying certain recalls and shipping new features to the Full Self-Driving suite.

Tesla seems to have the most seamless OTA processes, as many automakers have the ability to ship improvements through a simple software update.

We’re really excited to test the update, so when we get an opportunity to try out Comfort Braking when it makes it to our Model Y.

News

Tesla finally brings a Robotaxi update that Android users will love

The breakdown of the software version shows that Tesla is actively developing an Android-compatible version of the Robotaxi app, and the company is developing Live Activities for Android.

Tesla is finally bringing an update of its Robotaxi platform that Android users will love — mostly because it seems like they will finally be able to use the ride-hailing platform that the company has had active since last June.

Based on a decompile of software version 26.2.0 of the Robotaxi app, Tesla looks to be ready to roll out access to Android users.

According to the breakdown, performed by Tesla App Updates, the company is preparing to roll out an Android version of the app as it is developing several features for that operating system.

🚨 It looks like Tesla is preparing to launch the Robotaxi app for Android users at last!

A decompile of v26.2.0 of the Robotaxi app shows some progress on the Android side for Robotaxi 🤖 🚗 https://t.co/mThmoYuVLy

— TESLARATI (@Teslarati) March 13, 2026

The breakdown of the software version shows that Tesla is actively developing an Android-compatible version of the Robotaxi app, and the company is developing Live Activities for Android:

“Strings like notification_channel_robotaxid_trip_name and android_native_alicorn_eta_text show exactly how Tesla plans to replicate the iOS Live Activities experience. Instead of standard push alerts, Android users are getting a persistent, dynamically updating notification channel.”

This is a big step forward for several reasons. From a face-value perspective, Tesla is finally ready to offer Robotaxi to Android users.

The company has routinely prioritized Apple releases because there is a higher concentration of iPhone users in its ownership base. Additionally, the development process for Apple is simply less laborious.

Tesla is working to increase Android capabilities in its vehicles

Secondly, the Robotaxi rollout has been a typical example of “slowly then all at once.”

Tesla initially released Robotaxi access to a handful of media members and influencers. Eventually, it was expanded to more users, so that anyone using an iOS device could download the app and hail a semi-autonomous ride in Austin or the Bay Area.

Opening up the user base to Android users may show that Tesla is preparing to allow even more users to utilize its Robotaxi platform, and although it seems to be a few months away from only offering fully autonomous rides to anyone with app access, the expansion of the user base to an entirely different user base definitely seems like its a step in the right direction.

News

Lucid unveils Lunar Robotaxi in bid to challenge Tesla’s Cybercab in the autonomous ride hailing race

Lucid’s Lunar robotaxi is gunning for Tesla’s Cybercab in the autonomous ride hailing race

![Lucid Lunar robotaxi concept [Credit: Rendering by TESLARATI]](https://www.teslarati.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/03/lucid-lunar-robotaxi-concept-teslarati-rendering.jpg)

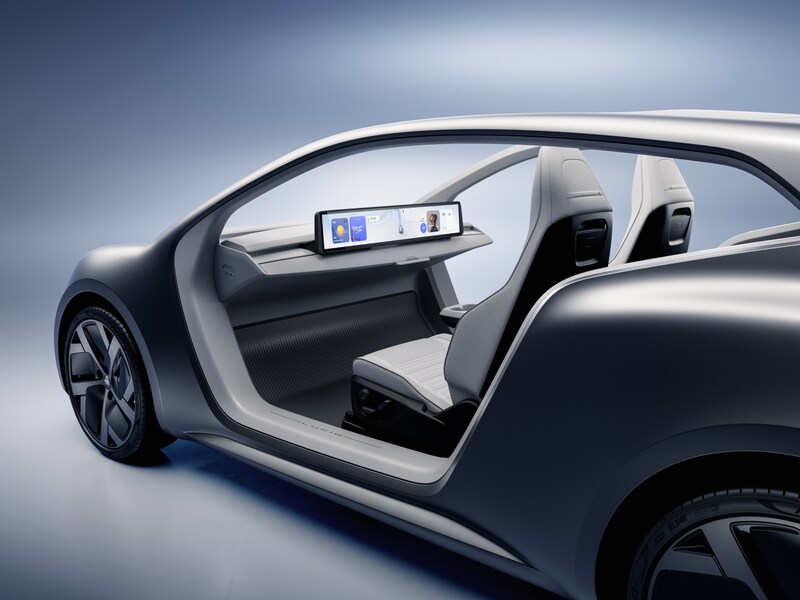

Lucid Group pulled back the curtain on its purpose-built autonomous robotaxi platform dubbed the Lunar Concept. Announced at its New York investor day event, Lunar is arguably the company’s most ambitious concept yet, and a direct line of sight toward the autonomous ride haling market that Tesla looks to control.

At Lucid Investor Day 2026, the company introduced Lunar, a purpose-built robotaxi concept based on the Midsize platform.

A comparison to Tesla’s Cybercab is unavoidable. The concept of a Tesla robotaxi was first introduced by Elon Musk back in April 2019 during an event dubbed “Autonomy Day,” where he envisioned a network of self-driving Tesla vehicles transporting passengers while not in use by their owners. That vision took another major step in October 2024 when, Musk unveiled the Cybercab at the Tesla “We, Robot” event held at Warner Bros. Studios in Burbank, California, where 20 concept Cybercabs autonomously drove around the studio lot giving rides to attendees.

Fast forward to today, and Tesla’s ambitions are finally materializing, but not without friction. As we recently reported, the Cybercab is being spotted with increasing frequency on public roads and across the grounds of Gigafactory Texas, suggesting that the company’s road testing and validation program is ramping meaningfully ahead of mass production. Tesla already operates a small scale robotaxi service in Austin using supervised Model Ys, but the Cybercab is designed from the ground up for high-volume, low-cost production, with Musk stating an eventual goal of producing one vehicle every 10 seconds.

At Lucid Investor Day 2026, the company introduced Lunar, a purpose-built robotaxi concept based on the Midsize platform.

Into this landscape steps Lucid’s Lunar. Built on the company’s all-new Midsize EV platform, which will also underpin consumer SUVs starting below $50,000. The Lunar mirrors the Cybercab’s core philosophy of having two seats, no driver controls, and a focus on fleet economics. The platform introduces Lucid’s redesigned Atlas electric drive unit, engineered to be smaller, lighter, and cheaper to manufacture at scale.

Unlike Tesla’s strategy of building its own ride hailing network from scratch, Lucid is partnering with Uber. The companies are said to be in advanced discussions to deploy Midsize platform vehicles at large scale, with Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi publicly backing Lucid’s engineering credentials and autonomous-ready architecture.

In the investor day event, Lucid also outlined a recurring software revenue model, with an in-vehicle AI assistant and monthly autonomous driving subscriptions priced between $69 and $199. This can be seen as a nod to the software revenue stream that Tesla has long championed with its Full Self-Driving subscription.

Tesla’s Cybercab is targeting a price point below $30k and with operating costs as low as 20 cents per mile. But with regulatory hurdles still ahead, the window for competition is open. Lucid’s Lunar may not have a launch date yet, but it arrives at a pivotal moment, and when the robotaxi race is no longer viewed as hypothetical. Rather, every serious EV player needs to come to bat on the same plate that Tesla has had countless practice swings on over the last seven years.

![Lucid Lunar robotaxi concept [Credit: Rendering by TESLARATI]](https://www.teslarati.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/03/lucid-lunar-robotaxi-concept-teslarati-rendering-80x80.jpg)