News

SpaceX reveals Starship “marine recovery” plans in new job postings

In a series of new job postings, SpaceX has hinted at an unexpected desire to develop “marine recovery systems for the Starship program.”

Since SpaceX first began bending metal for its steel Starship development program in late 2018, CEO Elon Musk, executives, and the company itself have long maintained that both Super Heavy boosters and Starship upper stages would perform what are known as return-to-launch-site (RTLS) landings. It’s no longer clear if those long-stated plans are set in stone.

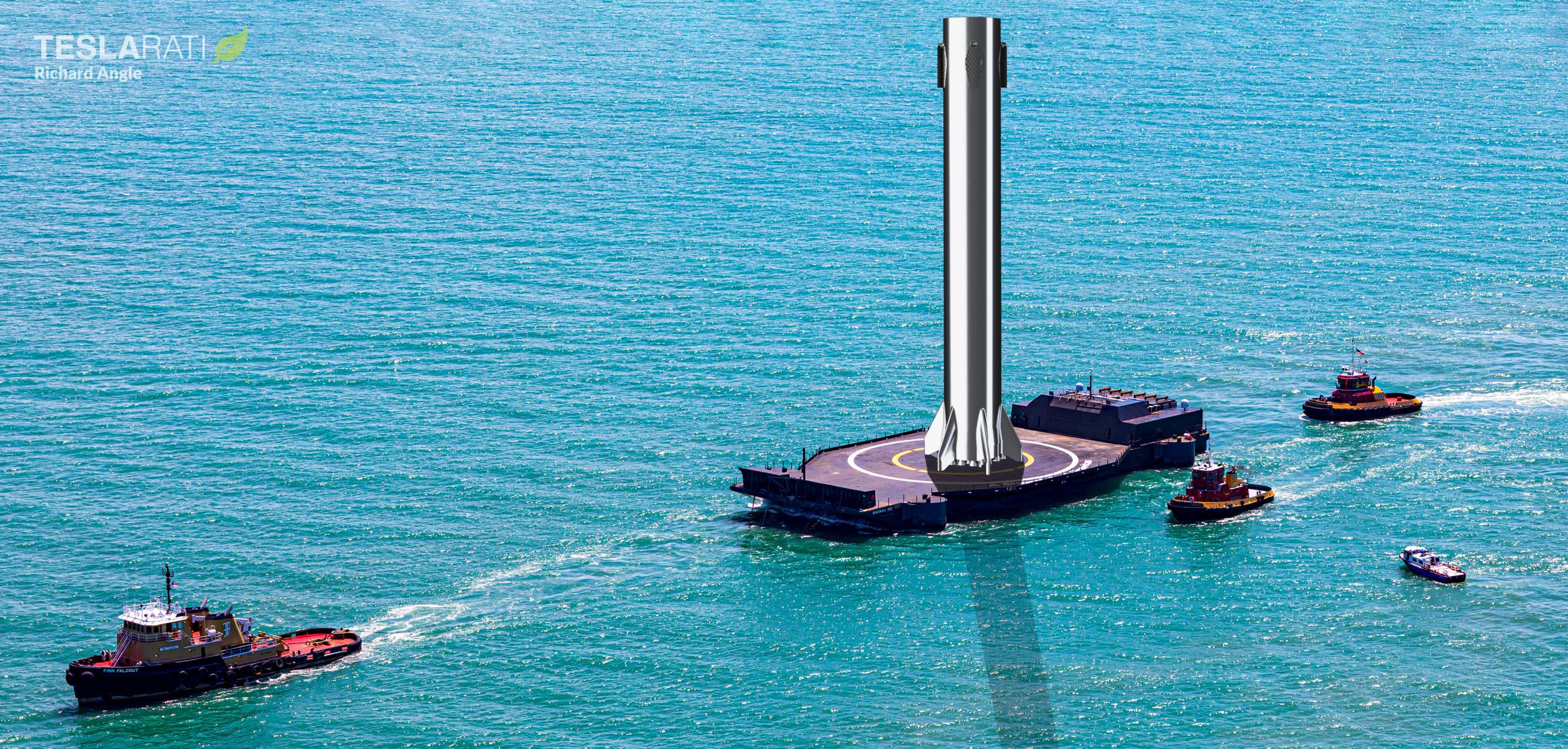

Oddly, despite repeatedly revealing plans to develop “marine recovery” assets for Starship, SpaceX’s recent “marine engineer” and “naval architect” job postings never specifically mentioned the company’s well-established plans to convert retired oil rigs into vast floating Starship launch sites. Weighing several thousand tons and absolutely dwarfing the football-field-sized drone ships SpaceX recovers Falcon boosters with, it goes without saying that towing an entire oil rig hundreds of miles to and from port is not an efficient or economical solution for rocket recovery. It would also make very little sense for SpaceX to hire a dedicated naval architect without once mentioning that they’d be working on something as all-encompassing as the world’s largest floating launch pad.

That leaves three obvious explanations for the mentions. First, it might be possible that SpaceX is merely preparing for the potential recovery of debris or intact, floating ships or boosters after intentionally expending them on early orbital Starship test flights. Second, SpaceX might have plans to strip an oil rig or two – without fully converting them into launch pads – and then use those rigs as landing platforms designed to remain at sea indefinitely. Those platforms might then transfer landed ships or boosters to smaller support ships tasked with returning them to dry land. Third and arguably most likely, SpaceX might be exploring the possible benefits of landing Super Heavy boosters at sea.

Through its Falcon rockets, SpaceX has slowly but surely refined and perfected the recovery and reuse of orbital-class rocket boosters – 24 (out of 103) of which occurred back on land. Rather than coasting 500-1000 kilometers (300-600+ mi) downrange after stage separation and landing on a drone ship at sea, those 24 boosters flipped around, canceled out their substantial velocities, and boosted themselves a few hundred kilometers back to the Florida or California coast, where they finally touched down on basic concrete pads.

Unsurprisingly, canceling out around 1.5 kilometers per second of downrange velocity (equivalent to Mach ~4.5) and fully reversing that velocity back towards the launch site is an expensive maneuver, costing quite a lot of propellant. For example, the nominal 25-second reentry burn performed by almost all Falcon boosters likely costs about 20 tons (~40,000 lb) of propellant. The average ~35-second single-engine landing burn used by all Falcon boosters likely costs about 10 tons (~22,000 lb) of propellant. Normally, that’s all that’s needed for a drone ship booster landing.

For RTLS landings, Falcon boosters must also perform a large ~40-second boostback burn with three Merlin 1D engines, likely costing an extra 25-35 tons (55,000-80,000 lb) of propellant. In other words, an RTLS landing generally ends up costing at least twice as much propellant as a drone ship landing. Using the general rocketry rule of thumb that every 7 kilograms of booster mass reduces payload to orbit by 1 kilogram and assuming that each reusable Falcon booster requires about 3 tons of recovery-specific hardware (mostly legs and grid fins) a drone ship landing might reduce Falcon 9’s payload to low Earth orbit (LEO) by ~5 tons (from 22 tons to 17 tons). The extra propellant needed for an RTLS landing might reduce it by another 4-5 tons to 13 tons.

Likely less than coincidentally, a Falcon 9 with drone ship booster recovery has never launched more than ~16 tons to LEO. While SpaceX hasn’t provided NASA’s ELVPerf calculator with data for orbits lower than 400 kilometers (~250 mi), it generally agrees, indicating that Falcon 9 is capable of launching about 12t with an RTLS landing and 16t with a drone ship landing.

This is all to say that landing reusable boosters at sea will likely always be substantially more efficient. The reason that SpaceX has always held that Starship’s Super Heavy boosters will avoid maritime recovery is that landing and recovering giant rocket boosters at sea is inherently difficult, risky, time-consuming, and expensive. That makes rapid reuse (on the order of multiple times per day or week) almost impossible and inevitably adds the cost of recovery, which could actually be quite significant for a rocket that SpaceX wants to eventually cost just a few million dollars per launch. However, so long as at-sea recovery costs less than a few million dollars, there’s always a chance that certain launch profiles could be drastically simplified – and end up cheaper – by the occasional at-sea booster landing.

If the alternative is a second dedicated launch to partially refuel one Starship, it’s possible that a sea landing could give Starship the performance needed to accomplish the same mission in a single launch, lowering the total cost of launch services. If – like with Falcon 9 – a sea landing could boost Starship’s payload to LEO by a third or more, the regular sea recovery of Super Heavy boosters would also necessarily cut the number of launches SpaceX needs to fill up a Starship Moon lander by a third. Given that SpaceX and NASA have been planning for Starship tanker launches to occur ~12 days apart, recovering boosters at sea becomes even more feasible.

In theory, the Starship launch vehicle CEO Elon Musk has recently described could be capable of launching anywhere from 150 to 200+ tons to low Earth orbit with full reuse and RTLS booster recovery. With so much performance available, it may matter less than it does with Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy if an RTLS booster landing cuts payload to orbit by a third, a half, or even more. At the end of the day, “just” 100 tons to LEO may be more than enough to satisfy any realistic near-term performance requirements.

But until Starships and Super Heavy boosters are reusable enough to routinely launch multiple times per week (let alone per day) and marginal launch costs have been slashed to single-digit millions of dollars, it’s hard to imagine SpaceX willingly leaving so much performance on the table by forgoing at-sea recovery out of principle alone.

News

Tesla adds awesome new driving feature to Model Y

Tesla is rolling out a new “Comfort Braking” feature with Software Update 2026.8. The feature is exclusive to the new Model Y, and is currently unavailable for any other vehicle in the Tesla lineup.

Tesla is adding an awesome new driving feature to Model Y vehicles, effective on Juniper-updated models considered model year 2026 or newer.

Tesla is rolling out a new “Comfort Braking” feature with Software Update 2026.8. The feature is exclusive to the new Model Y, and is currently unavailable for any other vehicle in the Tesla lineup.

Tesla writes in the release notes for the feature:

“Your Tesla now provides a smoother feel as you come to a complete stop during routine braking.”

🚨 Tesla has added a new “Comfort Braking” update with 2026.8

“Your Tesla provides a smoother feel as you come to a complete stop during routine braking.” https://t.co/afqCpBSVeA pic.twitter.com/C6MRmzfzls

— TESLARATI (@Teslarati) March 13, 2026

Interestingly, we’re not too sure what catalyzed Tesla to try to improve braking smoothness, because it hasn’t seemed overly abrupt or rough from my perspective. Although the brake pedal in my Model Y is rarely used due to Regenerative Braking, it seems Tesla wanted to try to make the ride comfort even smoother for owners.

There is always room for improvement, though, and it seems that there is a way to make braking smoother for passengers while the vehicle is coming to a stop.

This is far from the first time Tesla has attempted to improve its ride comfort through Over-the-Air updates, as it has rolled out updates to improve regenerative braking performance, handling while using Full Self-Driving, improvements to Steer-by-Wire to Cybertruck, and even recent releases that have combatted Active Road Noise.

Tesla holds a unique ability to change the functionality of its vehicles through software updates, which have come in handy for many things, including remedying certain recalls and shipping new features to the Full Self-Driving suite.

Tesla seems to have the most seamless OTA processes, as many automakers have the ability to ship improvements through a simple software update.

We’re really excited to test the update, so when we get an opportunity to try out Comfort Braking when it makes it to our Model Y.

News

Tesla finally brings a Robotaxi update that Android users will love

The breakdown of the software version shows that Tesla is actively developing an Android-compatible version of the Robotaxi app, and the company is developing Live Activities for Android.

Tesla is finally bringing an update of its Robotaxi platform that Android users will love — mostly because it seems like they will finally be able to use the ride-hailing platform that the company has had active since last June.

Based on a decompile of software version 26.2.0 of the Robotaxi app, Tesla looks to be ready to roll out access to Android users.

According to the breakdown, performed by Tesla App Updates, the company is preparing to roll out an Android version of the app as it is developing several features for that operating system.

🚨 It looks like Tesla is preparing to launch the Robotaxi app for Android users at last!

A decompile of v26.2.0 of the Robotaxi app shows some progress on the Android side for Robotaxi 🤖 🚗 https://t.co/mThmoYuVLy

— TESLARATI (@Teslarati) March 13, 2026

The breakdown of the software version shows that Tesla is actively developing an Android-compatible version of the Robotaxi app, and the company is developing Live Activities for Android:

“Strings like notification_channel_robotaxid_trip_name and android_native_alicorn_eta_text show exactly how Tesla plans to replicate the iOS Live Activities experience. Instead of standard push alerts, Android users are getting a persistent, dynamically updating notification channel.”

This is a big step forward for several reasons. From a face-value perspective, Tesla is finally ready to offer Robotaxi to Android users.

The company has routinely prioritized Apple releases because there is a higher concentration of iPhone users in its ownership base. Additionally, the development process for Apple is simply less laborious.

Tesla is working to increase Android capabilities in its vehicles

Secondly, the Robotaxi rollout has been a typical example of “slowly then all at once.”

Tesla initially released Robotaxi access to a handful of media members and influencers. Eventually, it was expanded to more users, so that anyone using an iOS device could download the app and hail a semi-autonomous ride in Austin or the Bay Area.

Opening up the user base to Android users may show that Tesla is preparing to allow even more users to utilize its Robotaxi platform, and although it seems to be a few months away from only offering fully autonomous rides to anyone with app access, the expansion of the user base to an entirely different user base definitely seems like its a step in the right direction.

News

Lucid unveils Lunar Robotaxi in bid to challenge Tesla’s Cybercab in the autonomous ride hailing race

Lucid’s Lunar robotaxi is gunning for Tesla’s Cybercab in the autonomous ride hailing race

![Lucid Lunar robotaxi concept [Credit: Rendering by TESLARATI]](https://www.teslarati.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/03/lucid-lunar-robotaxi-concept-teslarati-rendering.jpg)

Lucid Group pulled back the curtain on its purpose-built autonomous robotaxi platform dubbed the Lunar Concept. Announced at its New York investor day event, Lunar is arguably the company’s most ambitious concept yet, and a direct line of sight toward the autonomous ride haling market that Tesla looks to control.

At Lucid Investor Day 2026, the company introduced Lunar, a purpose-built robotaxi concept based on the Midsize platform.

A comparison to Tesla’s Cybercab is unavoidable. The concept of a Tesla robotaxi was first introduced by Elon Musk back in April 2019 during an event dubbed “Autonomy Day,” where he envisioned a network of self-driving Tesla vehicles transporting passengers while not in use by their owners. That vision took another major step in October 2024 when, Musk unveiled the Cybercab at the Tesla “We, Robot” event held at Warner Bros. Studios in Burbank, California, where 20 concept Cybercabs autonomously drove around the studio lot giving rides to attendees.

Fast forward to today, and Tesla’s ambitions are finally materializing, but not without friction. As we recently reported, the Cybercab is being spotted with increasing frequency on public roads and across the grounds of Gigafactory Texas, suggesting that the company’s road testing and validation program is ramping meaningfully ahead of mass production. Tesla already operates a small scale robotaxi service in Austin using supervised Model Ys, but the Cybercab is designed from the ground up for high-volume, low-cost production, with Musk stating an eventual goal of producing one vehicle every 10 seconds.

At Lucid Investor Day 2026, the company introduced Lunar, a purpose-built robotaxi concept based on the Midsize platform.

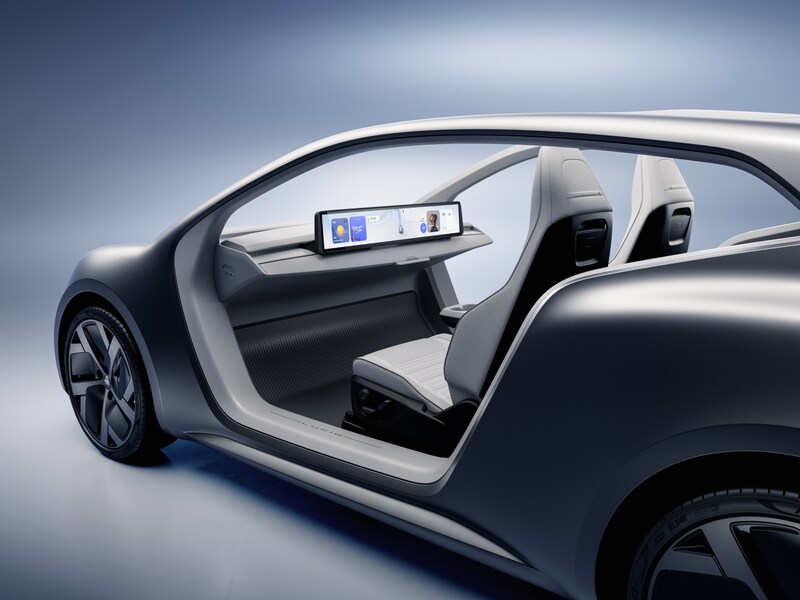

Into this landscape steps Lucid’s Lunar. Built on the company’s all-new Midsize EV platform, which will also underpin consumer SUVs starting below $50,000. The Lunar mirrors the Cybercab’s core philosophy of having two seats, no driver controls, and a focus on fleet economics. The platform introduces Lucid’s redesigned Atlas electric drive unit, engineered to be smaller, lighter, and cheaper to manufacture at scale.

Unlike Tesla’s strategy of building its own ride hailing network from scratch, Lucid is partnering with Uber. The companies are said to be in advanced discussions to deploy Midsize platform vehicles at large scale, with Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi publicly backing Lucid’s engineering credentials and autonomous-ready architecture.

In the investor day event, Lucid also outlined a recurring software revenue model, with an in-vehicle AI assistant and monthly autonomous driving subscriptions priced between $69 and $199. This can be seen as a nod to the software revenue stream that Tesla has long championed with its Full Self-Driving subscription.

Tesla’s Cybercab is targeting a price point below $30k and with operating costs as low as 20 cents per mile. But with regulatory hurdles still ahead, the window for competition is open. Lucid’s Lunar may not have a launch date yet, but it arrives at a pivotal moment, and when the robotaxi race is no longer viewed as hypothetical. Rather, every serious EV player needs to come to bat on the same plate that Tesla has had countless practice swings on over the last seven years.

![Lucid Lunar robotaxi concept [Credit: Rendering by TESLARATI]](https://www.teslarati.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/03/lucid-lunar-robotaxi-concept-teslarati-rendering-80x80.jpg)