News

NASA snubbed SpaceX, common sense to overpay Boeing for astronaut launches, says audit

A detailed government audit has revealed that NASA went out of its way to overpay Boeing for its Commercial Crew Program (CCP) astronaut launch services, making a mockery of its fixed-price contract with the company and blatantly snubbing SpaceX throughout the process.

Over the last several years, the NASA inspector general has published a number of increasingly discouraging reports about Boeing’s behavior and track-record as a NASA contractor, and November 14th’s report is possibly the most concerning yet. On November 14th, NASA’s Office of the Inspector General (OIG) published a damning audit titled “NASA’s Management of Crew Transportation to the International Space Station [ISS]” (PDF).

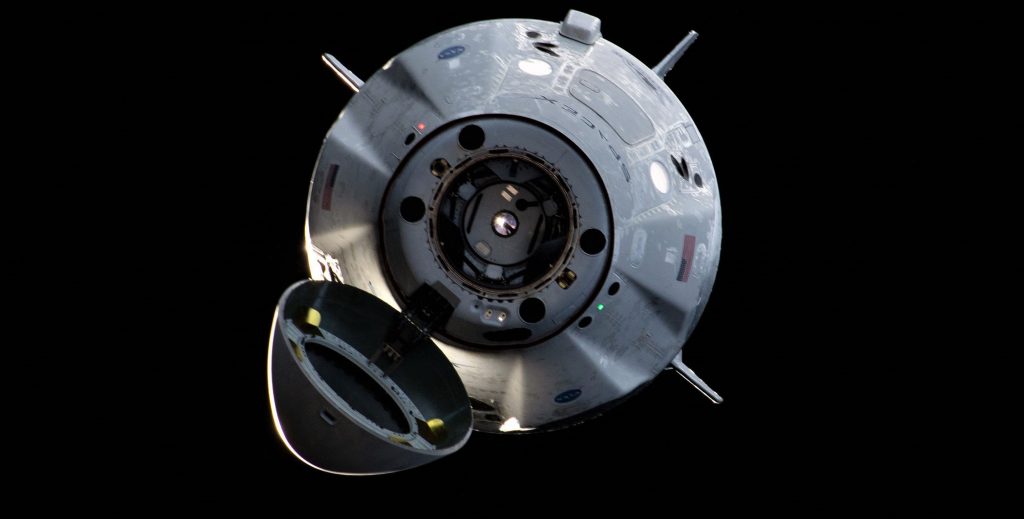

Offering more than 50 pages of detailed analysis of behavior that was at best inept and at worst deeply corrupt, OIG’s analysis uncovered some uncomfortable revelations about NASA’s relationship with Boeing in a different realm than usual: NASA’s Commercial Crew Program (CCP). Begun in the 2010s in an effort to develop multiple redundant commercial alternatives to the Space Shuttle, prematurely canceled before a US alternative was even on the horizon, the CCP ultimately awarded SpaceX and Boeing major development contracts in September 2014.

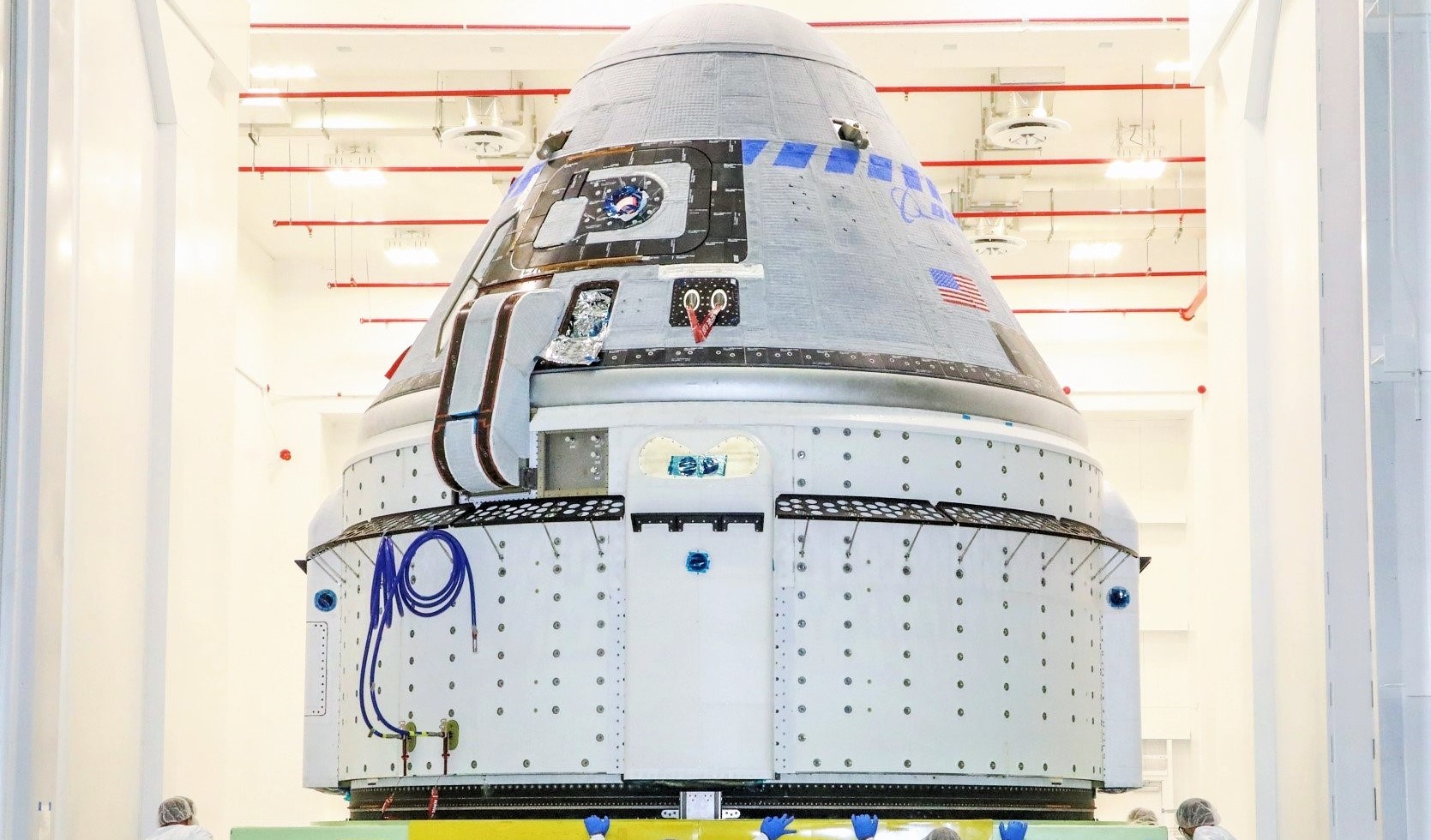

NASA awarded fixed-cost contracts worth $4.2 billion and $2.6 billion to Boeing and SpaceX, respectively, to essentially accomplish the same goals: design, build, test, and fly new spacecraft capable of transporting NASA astronauts to and from the International Space Station (ISS). The intention behind fixed-price contracts was to hold contractors responsible for any delays they might incur over the development of human-rated spacecraft, a task NASA acknowledged as challenging but far from unprecedented.

Off the rails

The most likely trigger of the bizarre events that would unfold a few years down the road began in part on June 28th, 2015 and culminated on September 1st, 2016, the dates of the two catastrophic failures SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket has suffered since its 2010 debut. In the most generous possible interpretation of the OIG’s findings, NASA headquarters and CCP managers may have been shaken and not thinking on an even keel after SpaceX’s second major failure in a little over a year.

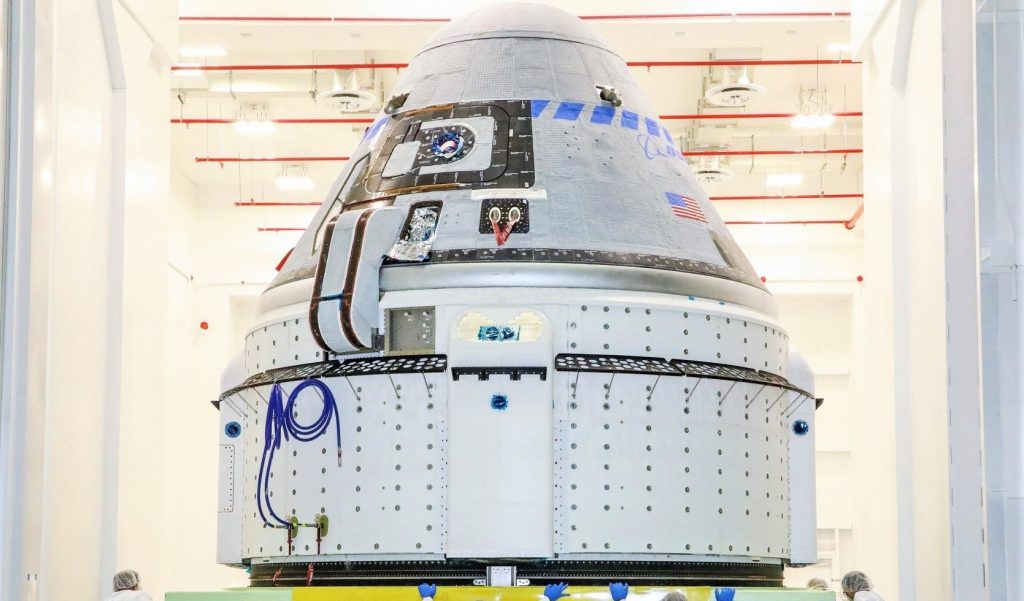

Under this stress, the agency may have ignored common sense and basic contracting due-diligence, leading “numerous officials” to sign off on a plan that would subvert Boeing’s fixed-price contract, paying the company an additional $287 million (~7%) to prevent a perceived gap in NASA astronaut access to the ISS. This likely arose because NASA briefly believed that SpaceX’s failures could cause multiple years of delays, making Boeing the only available crew transport provider for a significant period of time. Starliner was already delayed by more than a year, making it increasingly unlikely that Boeing alone would be able to ensure continuous NASA access to the ISS.

As NASA attempted to argue in its response to the audit, “the final price [increase] was agreed to by NASA and Boeing and was reviewed and approved by numerous NASA officials at the Kennedy Space Center and Headquarters”. In the heat of the moment, perhaps those officials forgot that Boeing had already purchased several Russian Soyuz seats to sell to NASA or tourists, and perhaps those officials missed the simple fact that those seats and some elementary schedule tweaks could have almost entirely alleviated the perceived “access gap” with minimal cost and effort.

The OIG audit further implied that the timing of a Boeing proposal – submitted just days after NASA agreed to pay the company extra to prevent that access gap – was suspect.

“Five days after NASA committed to pay $287.2 million in price increases for four commercial crew missions, Boeing submitted an official proposal to sell NASA up to five Soyuz seats for $373.5 million for missions during the same time period. In total, Boeing received $660.7 million above the fixed prices set in the CCtCap pricing tables to pay for an accelerated production timetable for four crew missions and five Soyuz seats.”

NASA OIG — November 14th, 2019 [PDF]

In other words, NASA officials somehow failed to realize or remember that Boeing owned multiple Soyuz seats during “prolonged negotiations” (p. 24) with Boeing and subsequently awarded Boeing an additional $287M to expedite Starliner production and preparations, thus averting an access gap. The very next week, Boeing asked NASA if it wanted to buy five Soyuz seats it had already acquired to send NASA astronauts to the ISS.

Bluntly speaking, this series of events has three obvious explanations, none of them particularly reassuring.

- Boeing intentionally withheld an obvious (partial) solution to a perceived gap in astronaut access to the ISS, exploiting NASA’s panic to extract a ~7% premium from its otherwise fixed-price Starliner development contract.

- Through gross negligence and a lack of basic contracting due-diligence, NASA ignored obvious (and cheaper) possible solutions at hand, taking Boeing’s word for granted and opening up the piggy bank.

- A farcical ‘crew access analysis’ study ignored multiple obvious and preferable solutions to give “numerous NASA officials” an excuse to violate fixed-price contracting principles and pay Boeing a substantial premium.

Extortion with a friendly smile

The latter explanation, while possibly the worst and most corruption-laden, is arguably the likeliest choice based on the history of NASA’s relationship with Boeing. In fact, a July 2019 report from the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) revealed that NASA was consistently paying Boeing hundreds of millions of dollars worth of “award fees” as part of the company’s SLS booster (core stage) production contract, which is no less than four years behind schedule and $1.8 billion over budget. From 2014 to 2018, NASA awarded Boeing a total of $271M in award fees, a practice meant to award a given contractor’s excellent performance.

In several of those years, NASA reviews reportedly described Boeing’s performance as “good”, “very good”, and “excellent”, all while Boeing repeatedly fumbled SLS core stage production, adding years of delays to the SLS rocket’s launch debut. This is to say that “numerous NASA officials” were also presumably more than happy to give Boeing hundreds of millions of dollars in awards even as the company was and is clearly a big reason why the SLS program continues to fail to deliver.

Ultimately, although NASA’s concern about SpaceX’s back-to-back Falcon 9 failures and some combination of ineptitude, ignorance, and corruption all clearly played a role, the fact remains that NASA – according to the inspector general – never approached SpaceX as part of their 2016/2017 efforts to prevent a ‘crew access gap’. Given that the CCP has two partners, that decision was highly improper regardless of the circumstances and is made even more inexplicable by the fact that NASA was apparently well aware that SpaceX’s Crew Dragon had significantly shorter lead times and far lower costs compared to Starliner.

This would have meant that had NASA approached SpaceX to attempt to mitigate the access gap, SpaceX could have almost certainly done it significantly cheaper and faster, or at minimum injected a bit of good-faith competition into the endeavor.

Finally and perhaps most disturbingly of all, NASA OIG investigators were told by “several NASA officials” that – in spite of several preferable alternatives – they ultimately chose to sign off Boeing’s demanded price increases because they were worried that Boeing would quit the Commercial Crew Program entirely without it. Boeing and NASA unsurprisingly denied this in their official responses to the OIG audit, but a US government inspector generally would never publish such a claim without substantial confidence and plenty of evidence to support it.

According to OIG sources, “senior CCP officials believed that due to financial considerations, Boeing could not continue as a commercial crew provider unless the contractor received the higher prices.” A lot remains unsaid, like why those officials believed that Boeing’s full withdrawal from CCP was a serious possibility and how they came to that conclusion, enough to make it impossible to conclude that Boeing legitimately threatened to quit in lieu of NASA payments.

All things considered, these fairly damning revelations should by no means take away from the excellent work Boeing engineers and technicians are trying to do to design, build, and launch Starliner. However, they do serve to draw a fine line between the mindsets and motivations of Boeing and SpaceX. One puts profit, shareholders, and itself above all else, while the other is trying hard to lower the cost of spaceflight and enable a sustainable human presence on the Moon, Mars, and beyond.

Check out Teslarati’s Marketplace! We offer Tesla accessories, including for the Tesla Cybertruck and Tesla Model 3.

News

Lucid unveils Lunar Robotaxi in bid to challenge Tesla’s Cybercab in the autonomous ride hailing race

Lucid’s Lunar robotaxi is gunning for Tesla’s Cybercab in the autonomous ride hailing race

![Lucid Lunar robotaxi concept [Credit: Rendering by TESLARATI]](https://www.teslarati.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/03/lucid-lunar-robotaxi-concept-teslarati-rendering.jpg)

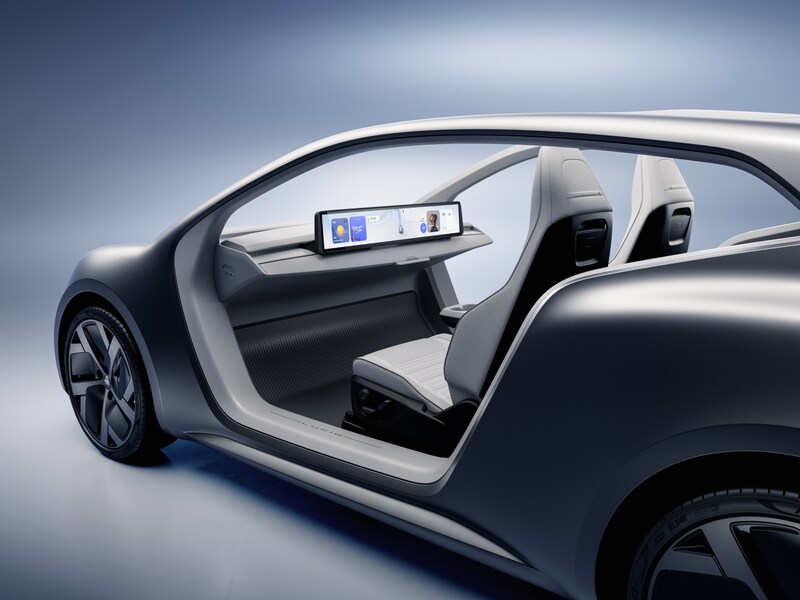

Lucid Group pulled back the curtain on its purpose-built autonomous robotaxi platform dubbed the Lunar Concept. Announced at its New York investor day event, Lunar is arguably the company’s most ambitious concept yet, and a direct line of sight toward the autonomous ride haling market that Tesla looks to control.

At Lucid Investor Day 2026, the company introduced Lunar, a purpose-built robotaxi concept based on the Midsize platform.

A comparison to Tesla’s Cybercab is unavoidable. The concept of a Tesla robotaxi was first introduced by Elon Musk back in April 2019 during an event dubbed “Autonomy Day,” where he envisioned a network of self-driving Tesla vehicles transporting passengers while not in use by their owners. That vision took another major step in October 2024 when, Musk unveiled the Cybercab at the Tesla “We, Robot” event held at Warner Bros. Studios in Burbank, California, where 20 concept Cybercabs autonomously drove around the studio lot giving rides to attendees.

Fast forward to today, and Tesla’s ambitions are finally materializing, but not without friction. As we recently reported, the Cybercab is being spotted with increasing frequency on public roads and across the grounds of Gigafactory Texas, suggesting that the company’s road testing and validation program is ramping meaningfully ahead of mass production. Tesla already operates a small scale robotaxi service in Austin using supervised Model Ys, but the Cybercab is designed from the ground up for high-volume, low-cost production, with Musk stating an eventual goal of producing one vehicle every 10 seconds.

At Lucid Investor Day 2026, the company introduced Lunar, a purpose-built robotaxi concept based on the Midsize platform.

Into this landscape steps Lucid’s Lunar. Built on the company’s all-new Midsize EV platform, which will also underpin consumer SUVs starting below $50,000. The Lunar mirrors the Cybercab’s core philosophy of having two seats, no driver controls, and a focus on fleet economics. The platform introduces Lucid’s redesigned Atlas electric drive unit, engineered to be smaller, lighter, and cheaper to manufacture at scale.

Unlike Tesla’s strategy of building its own ride hailing network from scratch, Lucid is partnering with Uber. The companies are said to be in advanced discussions to deploy Midsize platform vehicles at large scale, with Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi publicly backing Lucid’s engineering credentials and autonomous-ready architecture.

In the investor day event, Lucid also outlined a recurring software revenue model, with an in-vehicle AI assistant and monthly autonomous driving subscriptions priced between $69 and $199. This can be seen as a nod to the software revenue stream that Tesla has long championed with its Full Self-Driving subscription.

Tesla’s Cybercab is targeting a price point below $30k and with operating costs as low as 20 cents per mile. But with regulatory hurdles still ahead, the window for competition is open. Lucid’s Lunar may not have a launch date yet, but it arrives at a pivotal moment, and when the robotaxi race is no longer viewed as hypothetical. Rather, every serious EV player needs to come to bat on the same plate that Tesla has had countless practice swings on over the last seven years.

Elon Musk

Brazil Supreme Court orders Elon Musk and X investigation closed

The decision was issued by Supreme Court Justice Alexandre de Moraes following a recommendation from Brazil’s Prosecutor-General Paulo Gonet.

Brazil’s Supreme Federal Court has ordered the closure of an investigation involving Elon Musk and social media platform X. The inquiry had been pending for about two years and examined whether the platform was used to coordinate attacks against members of the judiciary.

The decision was issued by Supreme Court Justice Alexandre de Moraes following a recommendation from Brazil’s Prosecutor-General Paulo Gonet.

According to a report from Agencia Brasil, the investigation conducted by the Federal Police did not find evidence that X deliberately attempted to attack the judiciary or circumvent court orders.

Prosecutor-General Paulo Gonet concluded that the irregularities identified during the probe did not indicate fraudulent intent.

Justice Moraes accepted the prosecutor’s recommendation and ruled that the investigation should be closed. Under the ruling, the case will remain closed unless new evidence emerges.

The inquiry stemmed from concerns that content on X may have enabled online attacks against Supreme Court justices or violated rulings requiring the suspension of certain accounts under investigation.

Justice Moraes had previously taken several enforcement actions related to the platform during the broader dispute involving social media regulation in Brazil.

These included ordering a nationwide block of the platform, freezing Starlink accounts, and imposing fines on X totaling about $5.2 million. Authorities also froze financial assets linked to X and SpaceX through Starlink to collect unpaid penalties and seized roughly $3.3 million from the companies’ accounts.

Moraes also imposed daily fines of up to R$5 million, about $920,000, for alleged evasion of the X ban and established penalties of R$50,000 per day for VPN users who attempted to bypass the restriction.

Brazil remains an important market for X, with roughly 17 million users, making it one of the platform’s larger user bases globally.

The country is also a major market for Starlink, SpaceX’s satellite internet service, which has surpassed one million subscribers in Brazil.

Elon Musk

FCC chair criticizes Amazon over opposition to SpaceX satellite plan

Carr made the remarks in a post on social media platform X.

U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Chairman Brendan Carr criticized Amazon after the company opposed SpaceX’s proposal to launch a large satellite constellation that could function as an orbital data center network.

Carr made the remarks in a post on social media platform X.

Amazon recently urged the FCC to reject SpaceX’s application to deploy a constellation of up to 1 million low Earth orbit satellites that could serve as artificial intelligence data centers in space.

The company described the proposal as a “lofty ambition rather than a real plan,” arguing that SpaceX had not provided sufficient details about how the system would operate.

Carr responded by pointing to Amazon’s own satellite deployment progress.

“Amazon should focus on the fact that it will fall roughly 1,000 satellites short of meeting its upcoming deployment milestone, rather than spending their time and resources filing petitions against companies that are putting thousands of satellites in orbit,” Carr wrote on X.

Amazon has declined to comment on the statement.

Amazon has been working to deploy its Project Kuiper satellite network, which is intended to compete with SpaceX’s Starlink service. The company has invested more than $10 billion in the program and has launched more than 200 satellites since April of last year.

Amazon has also asked the FCC for a 24-month extension, until July 2028, to meet a requirement to deploy roughly 1,600 satellites by July 2026, as noted in a CNBC report.

SpaceX’s Starlink network currently has nearly 10,000 satellites in orbit and serves roughly 10 million customers. The FCC has also authorized SpaceX to deploy 7,500 additional satellites as the company continues expanding its global satellite internet network.

![Lucid Lunar robotaxi concept [Credit: Rendering by TESLARATI]](https://www.teslarati.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/03/lucid-lunar-robotaxi-concept-teslarati-rendering-80x80.jpg)