SpaceX

SpaceX Falcon Heavy completes successful rehearsal, static fire pushed back due to bug in launch pad hardware

More than a decade after its 2005 public conception, SpaceX is closer than ever to the first launch Falcon Heavy, the company’s newest rocket. Earlier this afternoon, the vehicle was aiming for its first static fire test, in which all 27 of its engines would be ignited (nearly) simultaneously in order to test procedures and the rocket itself. This attempt was sadly scrubbed, but only after the vehicle apparently completed a successful wet dress rehearsal, which saw Falcon Heavy fully loaded with propellant. According to Orlando’s News 13, the attempt was scrubbed only after one of eight hold-down clamps showed signs of bugs.

Falcon Heavy vertical at Pad 39A on Thursday, January 11. After a successful rehearsal, the static fire was scrubbed due to a small hardware bug. (Tom Cross/Teslarati)

Falcon Heavy vertical at Pad 39A on Thursday, January 11. After a successful rehearsal, the static fire was scrubbed due to a small hardware bug. (Tom Cross/Teslarati)

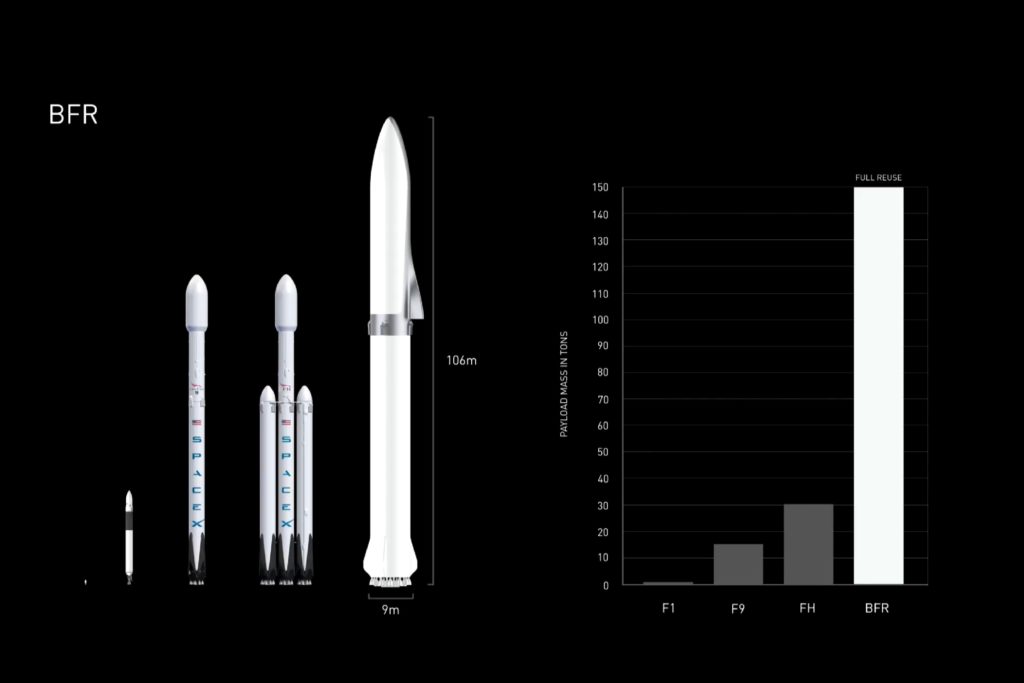

While Falcon Heavy is not explicitly critical for SpaceX’s near-term launch business and its loftier future goals, the development and operation of such a massive launch vehicle will likely serve as a strong foundation as the company transitions more aggressively into the design, engineering, and manufacture of its still-larger BFR series of rocket boosters and upper stages. Falcon Heavy stands approximately as tall as Falcon 9 at around 70 m (230 ft), but features three times the thrust and a little less than three times the weight of SpaceX’s workhorse rocket. With 27 Merlin 1D engines to Falcon 9’s namesake nine, Falcon Heavy’s 22,800 kN (5,000,000 lbf) of thrust is a nearly inconceivably amount of power, equivalent to twenty Airbus A380 passenger jets at full throttle.

Why is Falcon Heavy important?

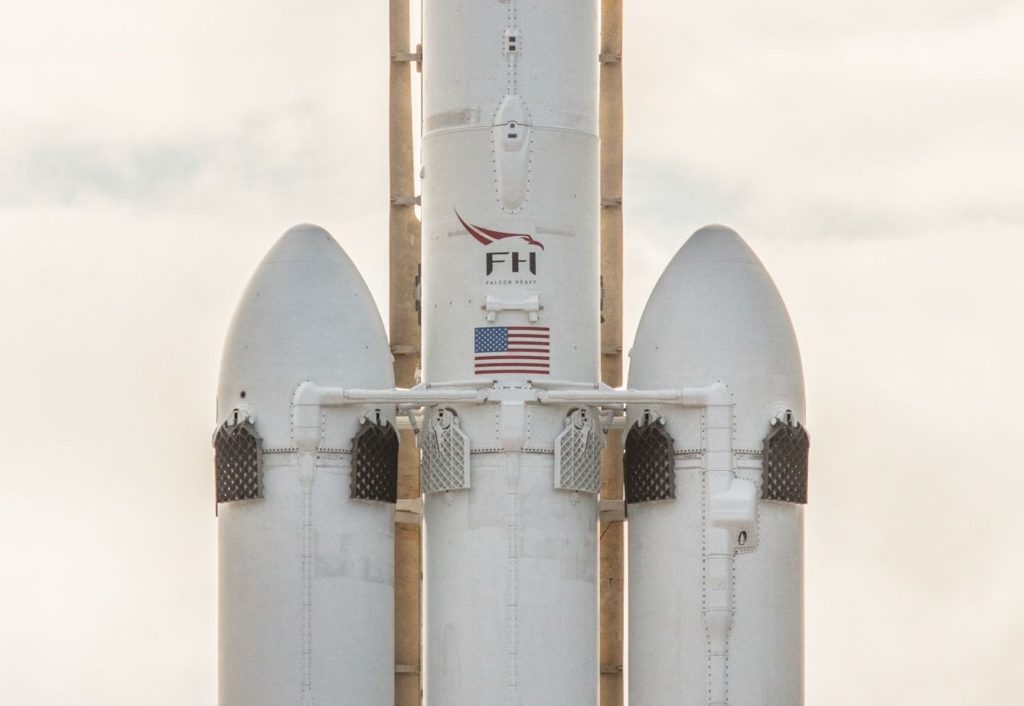

If SpaceX manages to pull off Falcon Heavy as a successful and reliable launch vehicle on the order of its reasonably successful Falcon 9, BFR may well be an easier vehicle to develop and operate, thanks to its single-core design. As Musk himself has discussed over the last year or so, the problem of safely and reliably distributing the thrust of Heavy’s side cores to the center core was unexpectedly difficult, as were the issues of igniting all 27 Merlin 1Ds and safely separating the side cores while in flight. Ultimately, the payload improvement (while in a fully reusable mode of operation) was quite small, particularly for the geostationary missions that make up essentially all prospective Falcon Heavy customer missions.

The additional complexity of recovery and refurbishing three separate Falcon 9 boosters almost simultaneously likely serves to only worsen the vehicle’s potential payoff, although the upcoming Block 5 iteration of Falcon 9 may partially improve the vehicle’s ease of operation. If Block 5 is indeed as reusable as SpaceX intends to make it, then a handful of Block 5 Falcon Heavy vehicles could presumably maintain a decent launch cadence for the vehicle without requiring costly and time-consuming shipping all over the continental US.

A closeup of Falcon Heavy’s three first stages, all featuring grid fins. The white bars in the center help to both distribute stress loads and separate the side cores from the center booster after launch. (SpaceX)

Nevertheless, the (hopefully successful) experience that will follow the launch and recovery operation of a super heavy-lift launch vehicle (SHLV) with ~30 first stage engines will be invaluable for SpaceX’s interplanetary goals. While BFR will be free of the complexity Falcon Heavy’s triple-core first stage added, it is still a massive vehicle that absolutely dwarfs anything SpaceX has attempted before. BFR in its 2017 iteration would mass around three times that of Falcon Heavy and feature 30 Raptor engines capable of approximately 53,000 kN (12,000,000 lbf) of thrust at liftoff, around 2.5x that of Heavy. Many, many other features mean that BFR and particularly BFS will be extraordinarily difficult to realize: BFS alone will be treading into truly unprecedented areas of spaceflight with the scale, longevity, and reusability it is intended to achieve while comfortably ferrying dozens of astronauts to and from Mars and the Moon.

However, the scale of BFR is equivalent to that of the famous Saturn V rocket that took astronauts to the Moon in the 1960s and 70s. In other words, while still dumbfoundingly massive and unprecedented in the modern era, rockets at the scale of BFR do in fact have a precedent of success, which lends the effort considerable plausibility, at least at proof-of-concept level. As of September 2017, Elon Musk suggested that SpaceX was aiming to begin construction of the first BFS (Big ____ Spaceship) by the end of Q2 2018, a truly Muskian deadline that probably wont hold. Still, if construction of the first prototype begins at any point in 2018, it will bode well for SpaceX’s aggressive timelines.

- Falcon Heavy’s three boosters and 27 Merlin 1D engines on full display. (SpaceX)

- BFR shown to scale with Falcon 1, 9, and Heavy. (SpaceX)

- .While SpaceX’s own visualizations are gorgeous and thrilling in their own rights, Romax’s interpretation adds an unparalleled level of shock and awe. (SpaceX)

In the meantime, BFR’s precursor Falcon Heavy has effectively completed its first wet dress rehearsal, although the static fire attempt was scrubbed for the day. This is understandable for such a complex and untested vehicle, especially after SpaceX’s exceptionally quick modifications to Pad 39A. While unofficial, word is that an issue with one of the Transport/Erector/Launcher’s (TEL) eight separate launch clamps caused the scrub. Those launch clamps ensure that the massive vehicle would stay put during a static fire, and the status of those clamps would be especially important during such an unusually long static fire of such a powerful rocket.

Stay tuned for updates on SpaceX’s upcoming launches and Falcon Heavy’s next static fire attempt, likely within the next several days. The vehicle’s inaugural launch date is effectively up in the air until the static fire has been successfully completed, but as of yesterday SpaceX was understood to be targeting January 26th. Delays are to be expected.

Follow along live as Teslarati’s launch photographer Tom Cross weathers the delays and covers the static fire attempt live from Cape Canaveral.

Elon Musk

Elon Musk outlines plan for first Starship tower catch attempt

Musk confirmed that Starship V3 Ship 1 (SN1) is headed for ground tests and expressed strong confidence in the updated vehicle design.

Elon Musk has clarified when SpaceX will first attempt to catch Starship’s upper stage with its launch tower. The CEO’s update provides the clearest teaser yet for the spacecraft’s recovery roadmap.

Musk shared the details in recent posts on X. In his initial post, Musk confirmed that Starship V3 Ship 1 (SN1) is headed for ground tests and expressed strong confidence in the updated vehicle design.

“Starship V3 SN1 headed for ground tests. I am highly confident that the V3 design will achieve full reusability,” Musk wrote.

In a follow-up post, Musk addressed when SpaceX would attempt to catch the upper stage using the launch tower’s robotic arms.

“Should note that SpaceX will only try to catch the ship with the tower after two perfect soft landings in the ocean. The risk of the ship breaking up over land needs to be very low,” Musk clarified.

His remarks suggest that SpaceX is deliberately reducing risk before attempting a tower catch of Starship’s upper stage. Such a milestone would mark a major step towards the full reuse of the Starship system.

SpaceX is currently targeting the first Starship V3 flight of 2026 this coming March. The spacecraft’s V3 iteration is widely viewed as a key milestone in SpaceX’s long-term strategy to make Starship fully reusable.

Starship V3 features a number of key upgrades over its previous iterations. The vehicle is equipped with SpaceX’s Raptor V3 engines, which are designed to deliver significantly higher thrust than earlier versions while reducing cost and weight.

The V3 design is also expected to be optimized for manufacturability, a critical step if SpaceX intends to scale the spacecraft’s production toward frequent launches for Starlink, lunar missions, and eventually Mars.

Elon Musk

Starlink powers Europe’s first satellite-to-phone service with O2 partnership

The service initially supports text messaging along with apps such as WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger, Google Maps and weather tools.

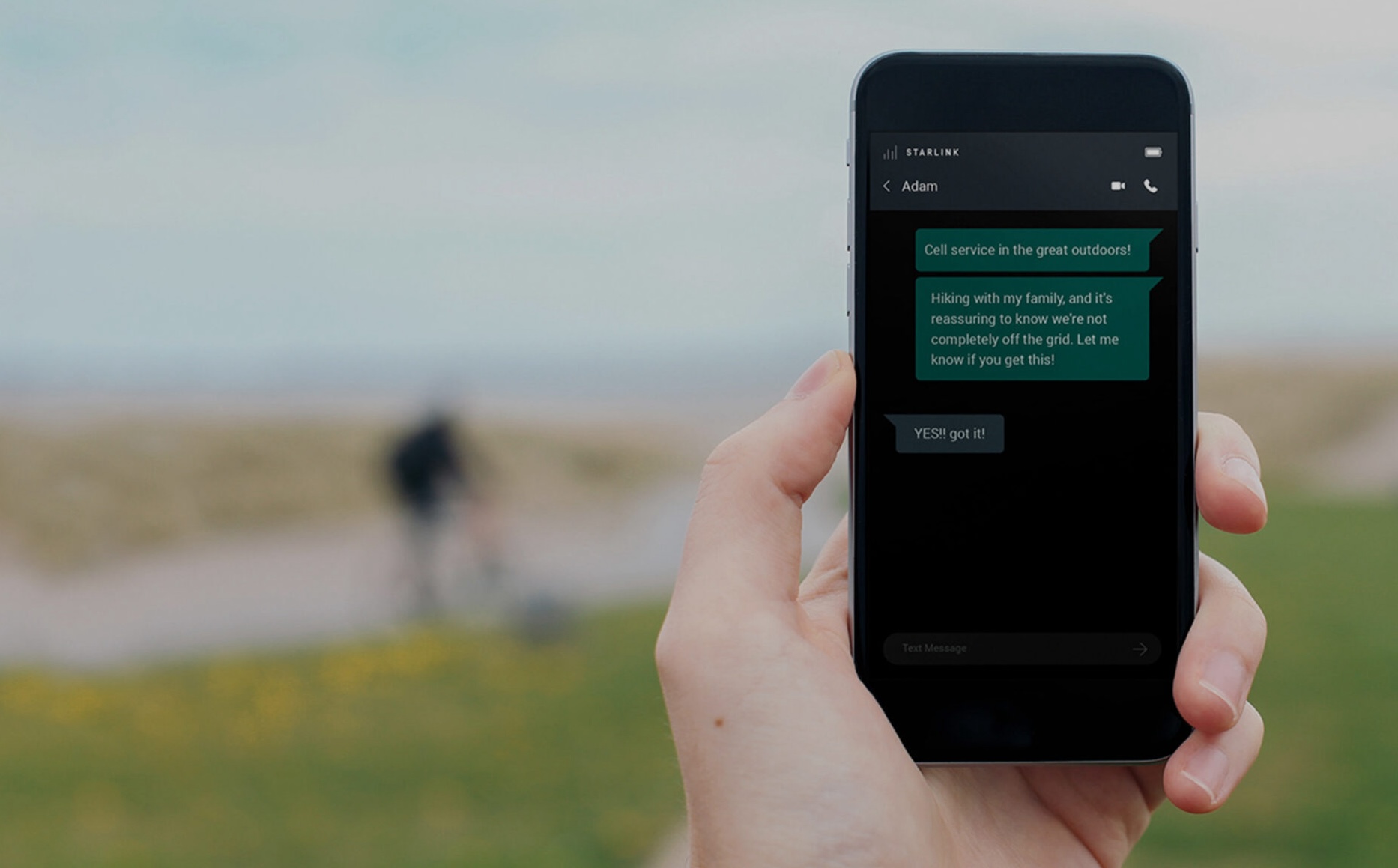

Starlink is now powering Europe’s first commercial satellite-to-smartphone service, as Virgin Media O2 launches a space-based mobile data offering across the UK.

The new O2 Satellite service uses Starlink’s low-Earth orbit network to connect regular smartphones in areas without terrestrial coverage, expanding O2’s reach from 89% to 95% of Britain’s landmass.

Under the rollout, compatible Samsung devices automatically connect to Starlink satellites when users move beyond traditional mobile coverage, according to Reuters.

The service initially supports text messaging along with apps such as WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger, Google Maps and weather tools. O2 is pricing the add-on at £3 per month.

By leveraging Starlink’s satellite infrastructure, O2 can deliver connectivity in remote and rural regions without building additional ground towers. The move represents another step in Starlink’s push beyond fixed broadband and into direct-to-device mobile services.

Virgin Media O2 chief executive Lutz Schuler shared his thoughts about the Starlink partnership. “By launching O2 Satellite, we’ve become the first operator in Europe to launch a space-based mobile data service that, overnight, has brought new mobile coverage to an area around two-thirds the size of Wales for the first time,” he said.

Satellite-based mobile connectivity is gaining traction globally. In the U.S., T-Mobile has launched a similar satellite-to-cell offering. Meanwhile, Vodafone has conducted satellite video call tests through its partnership with AST SpaceMobile last year.

For Starlink, the O2 agreement highlights how its network is increasingly being integrated into national telecom systems, enabling standard smartphones to connect directly to satellites without specialized hardware.

Elon Musk

Elon Musk’s Starbase, TX included in $84.6 million coastal funding round

The funds mark another step in the state’s ongoing beach restoration and resilience efforts along the Gulf Coast.

Elon Musk’s Starbase, Texas has been included in an $84.6 million coastal funding round announced by the Texas General Land Office (GLO). The funds mark another step in the state’s ongoing beach restoration and resilience efforts along the Gulf Coast.

Texas Land Commissioner Dawn Buckingham confirmed that 14 coastal counties will receive funding through the Coastal Management Program (CMP) Grant Cycle 31 and Coastal Erosion Planning and Response Act (CEPRA) program Cycle 14. Among the Brownsville-area recipients listed was the City of Starbase, which is home to SpaceX’s Starship factory.

“As someone who spent more than a decade living on the Texas coast, ensuring our communities, wildlife, and their habitats are safe and thriving is of utmost importance. I am honored to bring this much-needed funding to our coastal communities for these beneficial projects,” Commissioner Buckingham said in a press release.

“By dedicating this crucial assistance to these impactful projects, the GLO is ensuring our Texas coast will continue to thrive and remain resilient for generations to come.”

The official Starbase account acknowledged the support in a post on X, writing: “Coastal resilience takes teamwork. We appreciate @TXGLO and Commissioner Dawn Buckingham for their continued support of beach restoration projects in Starbase.”

The funding will support a range of coastal initiatives, including beach nourishment, dune restoration, shoreline stabilization, habitat restoration, and water quality improvements.

CMP projects are backed by funding from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the Gulf of Mexico Energy Security Act, alongside local partner matches. CEPRA projects focus specifically on reducing coastal erosion and are funded through allocations from the Texas Legislature, the Texas Hotel Occupancy Tax, and GOMESA.

Checks were presented in Corpus Christi and Brownsville to counties, municipalities, universities, and conservation groups. In addition to Starbase, Brownsville-area recipients included Cameron County, the City of South Padre Island, Willacy County, and the Willacy County Navigation District.