SpaceX

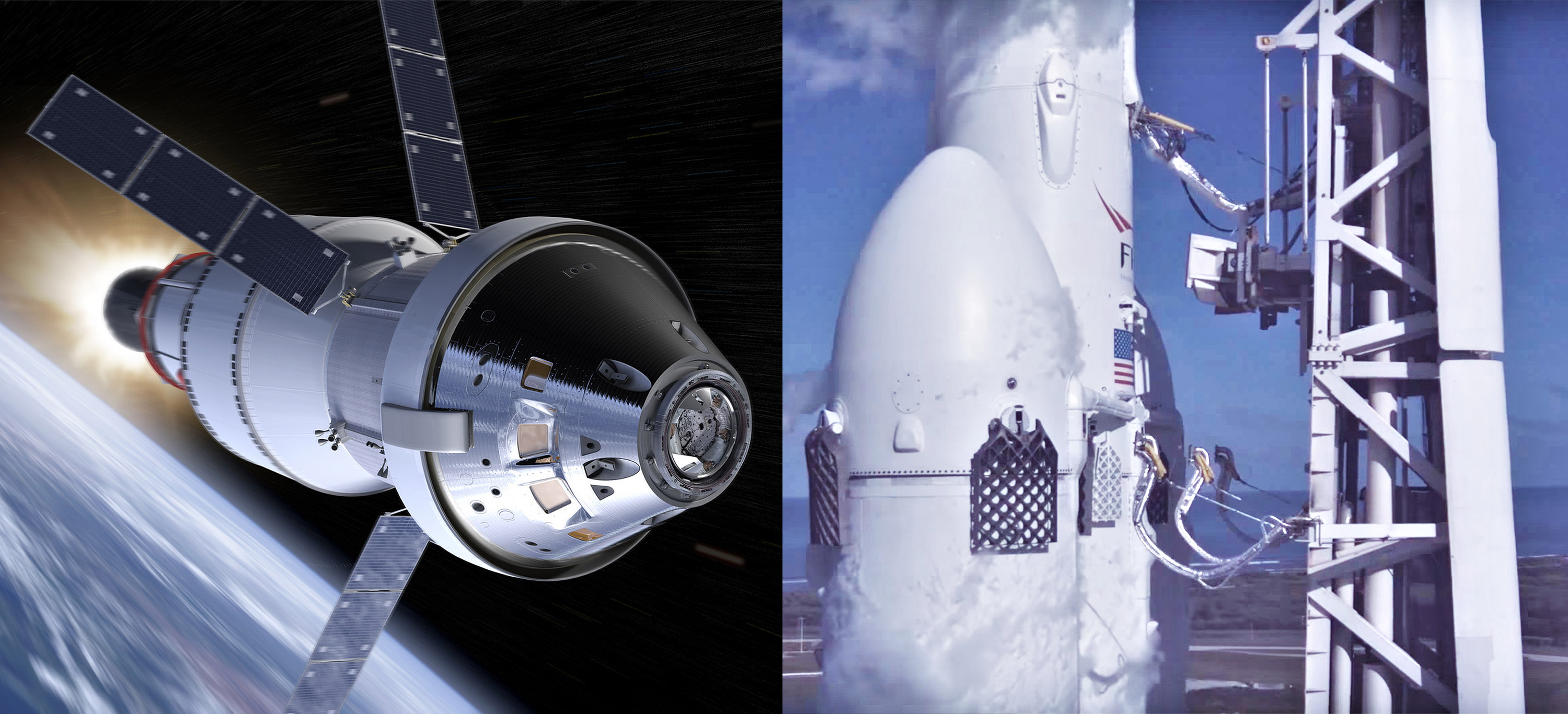

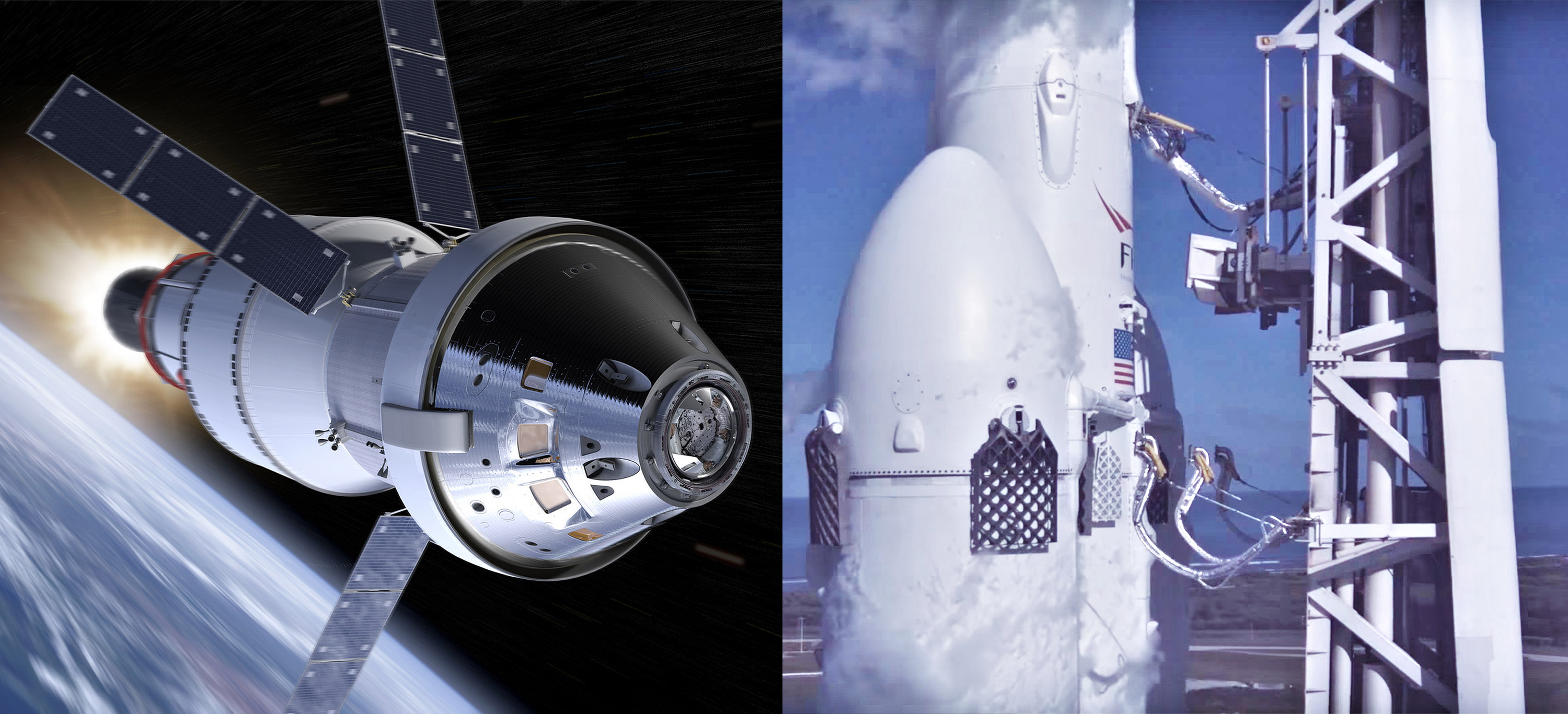

SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy shown launching NASA Orion spacecraft in fan render

A spaceflight fan’s unofficial render has offered the best look yet at what SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy could look like in the unlikely but not impossible event that NASA decides to launch its uncrewed Orion demonstration mission on commercial rockets.

Oddly enough, the thing that most stands out from artist brickmack’s interpretation of Orion and Falcon Heavy is just how relatively normal the large NASA spacecraft looks atop a SpaceX rocket. The render also serves as a visual reminder of just how little SpaceX would necessarily need to change or re-certify before Falcon Heavy would be able to launch Orion. Aside from the fact that NASA’s Launch Services Program (LSP) is not quite ready to certify the full launch vehicle for NASA missions, very few hurdles appear to stand in the way of Orion launching on a commercial rocket – be it on Falcon Heavy or ULA’s Delta IV Heavy.

In a wholly unexpected announcement made by NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine during a March 13th Congressional hearing, the agency leader revealed that NASA was seriously analyzing the possibility of launching Orion’s uncrewed lunar demonstration mission – known as Exploration Mission 1 (EM-1) – on commercial launch vehicles instead of the agency’s own Space Launch System (SLS) rocket.

The purpose: maintain the missions launch schedule – 2020 – in the face of a relentless barrage of delays facing the SLS rocket, the launch debut of which has effectively been slipped almost three years in the last 18 or so months, with the latest launch date now featuring a median target of November 2021. Some subset of NASA leaders, Congressional supporters, and White House officials have clearly begun to accept that SLS/Orion’s major continued delays are simply unacceptable to both the taxpayer and maintaining appearances, despite the fact that those delays continue to make SLS/Orion an extremely successful example of both corporate welfare and a jobs program.

As it currently stands, a median target of November 2021 for the SLS launch debut guarantees that there is almost certainly no chance of the rocket launching at any point in 2020, even if NASA took the extraordinary step of completely cutting a full-length static fire of the entirely unproven rocket prior to its debut. Known as the “Green Run”, the ~8-minute long static fire test is planned to occur at NASA’s Stennis Space Center on the B2 test stand, which NASA – despite continuous criticism from OIG before and after the decision – has spent more than $350M to refurbish. Stennis B2’s refurbishment was effectively completed just two months ago after the better part of seven years of work.

Put simply, even heroics verging on insanity would be unlikely to get SLS prime contractor Boeing to cut ~12 months off of the rocket’s schedule prevent additional unplanned delays in the 18 or so months between now and an even minutely plausible launch debut target. Admittedly, NASA’s proposed commercial alternative for Orion’s lunar launch debut also offers a range of different but equally concerning risks for the program and mission assurance.

Major challenges remain

On one hand, the task of successfully launching NASA’s Orion spacecraft around the Moon with Delta IV Heavy and Falcon Heavy rockets has a lot going for it, regardless of which rockets launch Orion to LEO or launch the fueled upper stage to boost it around the Moon. In 2014, NASA and ULA successfully launched a partial-fidelity Orion spacecraft to an altitude of 3700 miles (~6000 km), testing some of Orion’s avionics, general spacefaring capabilities, and the craft’s heat shield, although Lockheed Martin has since significantly changed the shield’s design and method of production/installation. Regardless, the EFT-1 test flight means that a solution already more or less exists to mate Orion and its service module (ESM) to a commercial rocket and launch the duo into orbit.

If ULA is unable to essentially produce a Delta IV Heavy from scratch in less than 12-18 months, Falcon Heavy would be next in line to launch Orion/ESM, a use-case that might actually be less absurd than it seems. Thanks to the fact that SpaceX’s payload fairing is actually wider than the large Orion spacecraft (5.2 m (17 ft) vs. 5 m (16.5 ft) in diameter), any major risks of radical aerodynamic problems can be largely retired, although that would still need to be verified with models and/or wind-tunnel testing. The only major change that would need to be certified is ensuring that the Falcon second stage is capable of supporting the Orion/ESM payload, weighing at least ~26 metric tons (~57,000 lb) at launch. The heaviest payloads SpaceX has launched thus far were likely its Iridium NEXT missions, weighing around 9600 kg (21,100 lb).

However, the most difficult aspects of Bridenstine’s proposed alternative are centered around the need for the EM-1 Orion spacecraft to somehow dock with a fueled upper stage meant to be launched separately. Orion in its current EM-1 configuration does not currently have the ability to dock with anything on orbit, a challenge that would require Lockheed Martin and subcontractors to find a way to install the proper hardware and computers and develop software that was – prior to this surprise announcement – only planned to fly on EM-3 (NET 2024). As such, Lockheed Martin – notorious for slow progress, cost overruns, and delays throughout the Orion program – would effectively become the critical path in finishing and installing on-orbit docking capabilities on Orion in less than 12-18 months.

The only alternative would be to have either SpaceX or ULA retrofit some sort of docking mechanism onto one of their upper stages, perhaps less difficult than getting Lockheed Martin to work expediently but still a major challenge for such a short developmental timeframe. Put simply, completing the tasks at hand in the time allotted could easily be beyond the capabilities of old-guard NASA contractors like LockMart and Boeing. Ironically, the upper stage that was designed for EM-1 and is already more or less complete – known as the interim cryogenic propulsion stage (ICPS) – is built by Boeing, the same company that has the most to lose if NASA chooses to make the SLS rocket – which Boeing also builds – functionally redundant with a commercial dual-launch alternative.

Second render in this series. Commercial transport for Orion from LEO to TLI in a dual-launch profile (this part is much harder in the near term, really need ACES unless the goal is only a flyby) https://t.co/70eG2i7Axz— Mack Crawford (@brickmack) March 24, 2019

With

Check out Teslarati’s Marketplace! We offer Tesla accessories, including for the Tesla Cybertruck and Tesla Model 3.

News

SpaceX’s Crew-11 mission targets July 31 launch amid tight ISS schedule

The flight will lift off from Launch Complex 39A at Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

NASA and SpaceX are targeting July 31 for the launch of Crew-11, the next crewed mission to the International Space Station (ISS). The flight will lift off from Launch Complex 39A at Kennedy Space Center in Florida, using the Crew Dragon Endeavour and a Falcon 9 booster.

Crew Dragon Endeavour returns

Crew-11 will be the sixth flight for Endeavour, making it SpaceX’s most experienced crew vehicle to date. According to SpaceX’s director of Dragon mission management, Sarah Walker, Endeavour has already carried 18 astronauts representing eight countries since its first mission with NASA’s Bob Behnken and Doug Hurley in 2020, as noted in an MSN report.

“This Dragon spacecraft has successfully flown 18 crew members representing eight countries to space already, starting with (NASA astronauts) Bob (Behnken) and Doug (Hurley) in 2020, when it returned human spaceflight capabilities to the United States for the first time since the shuttle retired in July of 2011,” Walker said.

For this mission, Endeavour will debut SpaceX’s upgraded drogue 3.1 parachutes, designed to further enhance reentry safety. The parachutes are part of SpaceX’s ongoing improvements to its human-rated spacecraft, and Crew-11 will serve as their first operational test.

The Falcon 9 booster supporting this launch is core B1094, which has launched in two previous Starlink missions, as well as the private Ax-4 mission on June 25, as noted in a Space.com report.

The four-members of Crew-11 are NASA astronauts Zena Cardman and Mike Fincke, as well as Japan’s Kimiya Yui and Russia’s Oleg Platonov.

Tight launch timing

Crew-11 is slated to arrive at the ISS just as NASA coordinates a sequence of missions, including the departure of Crew-10 and the arrival of SpaceX’s CRS-33 mission. NASA’s Bill Spetch emphasized the need for careful planning amid limited launch resources, noting the importance of maintaining station altitude and resupply cadence.

“Providing multiple methods for us to maintain the station altitude is critically important as we continue to operate and get the most use out of our limited launch resources that we do have. We’re really looking forward to demonstrating that capability with (CRS-33) showing up after we get through the Crew-11 and Crew-10 handover,” Spetch stated.

News

SpaceX launches Ax-4 mission to the ISS with international crew

The SpaceX Falcon 9 launched Axiom’s Ax-4 mission to ISS. Ax-4 crew will conduct 60+ science experiments during a 14-day stay on the ISS.

SpaceX launched the Falcon 9 rocket kickstarting Axiom Space’s Ax-4 mission to the International Space Station (ISS). Axiom’s Ax-4 mission is led by a historic international crew and lifted off from Kennedy Space Center’s Launch Complex 39A at 2:31 a.m. ET on June 25, 2025.

The Ax-4 crew is set to dock with the ISS around 7 a.m. ET on Thursday, June 26, 2025. Axiom Space, a Houston-based commercial space company, coordinated the mission with SpaceX for transportation and NASA for ISS access, with support from the European Space Agency and the astronauts’ governments.

The Ax-4 mission marks a milestone in global space collaboration. The Ax-4 crew, commanded by U.S. astronaut Peggy Whitson, includes Shubhanshu Shukla from India as the pilot, alongside mission specialists Sławosz Uznański-Wiśniewski from Poland and Tibor Kapu from Hungary.

“The trip marks the return to human spaceflight for those countries — their first government-sponsored flights in more than 40 years,” Axiom noted.

Shukla’s participation aligns with India’s Gaganyaan program planned for 2027. He is the first Indian astronaut to visit the ISS since Rakesh Sharma in 1984.

Axiom’s Ax-4 mission marks SpaceX’s 18th human spaceflight. The mission employs a Crew Dragon capsule atop a Falcon 9 rocket, designed with a launch escape system and “two-fault tolerant” for enhanced safety. The Axiom mission faced a few delays due to weather, a Falcon 9 leak, and an ISS Zvezda module leak investigation by NASA and Roscosmos before the recent successful launch.

As the crew prepares to execute its scientific objectives, SpaceX’s Ax-4 mission paves the way for a new era of inclusive space research, inspiring future generations and solidifying collaborative ties in the cosmos. During the Ax-4 crew’s 14-day stay in the ISS, the astronauts will conduct nearly 60 experiments.

“We’ll be conducting research that spans biology, material, and physical sciences as well as technology demonstrations,” said Whitson. “We’ll also be engaging with students around the world, sharing our experience and inspiring the next generation of explorers.”

SpaceX’s Ax-4 mission highlights Axiom’s role in advancing commercial spaceflight and fostering international partnerships. The mission strengthens global space exploration efforts by enabling historic spaceflight returns for India, Poland, and Hungary.

News

Starlink Cellular’s T-Mobile service to grow with third-party app data

From Oct 2025, T-Satellite will enable third-party apps in dead zones! WhatsApp, X, AccuWeather + more coming soon.

Starlink Cellular’s T-Mobile service will expand with third-party app data support starting in October, enhancing connectivity in cellular dead zones.

T-Mobile’s T-Satellite, supported by Starlink, launches officially on July 23. Following its launch, T-Mobile’s Starlink Cellular service will enable data access for third-party apps like WhatsApp, X, Google, Apple, AccuWeather, and AllTrails on October 1, 2025.

T-Mobile’s Starlink Cellular is currently in free beta. T-Satellite will add MMS support for Android phones on July 23, with iPhone support to follow. MMS support allows users to send images and audio clips alongside texts. By October, T-Mobile will extend emergency texting to all mobile users with compatible phones, beyond just T-Mobile customers, building on its existing 911 texting capability. The carrier also provides developer tools to help app makers integrate their software with T-Satellite’s data service, with plans to grow the supported app list.

T-Mobile announced these updates during an event celebrating an Ookla award naming it the best U.S. phone network, a remarkable turnaround from its last-place ranking a decade ago.

“We not only dream about going from worst to best, we actually do it. We’re a good two years ahead of Verizon and AT&T, and I believe that lead is going to grow,” said T-Mobile’s Chief Operating Officer Srini Gopalan.

T-Mobile unveiled two promotions for its Starlink Cellular services to attract new subscribers. A free DoorDash DashPass membership, valued at $10/month, will be included with popular plans like Experience Beyond and Experience More, offering reduced delivery and service fees. Meanwhile, the Easy Upgrade promotion targets Verizon customers by paying off their phone balances and providing flagship devices like the iPhone 16, Galaxy S25, or Pixel 9.

T-Mobile’s collaboration with SpaceX’s Starlink Cellular leverages orbiting satellites to deliver connectivity where traditional networks fail, particularly in remote areas. Supporting third-party apps underscores T-Mobile’s commitment to enhancing user experiences through innovative partnerships. As T-Satellite’s capabilities grow, including broader app integration and emergency access, T-Mobile is poised to strengthen its lead in the U.S. wireless market.

By combining Starlink’s satellite technology with strategic promotions, T-Mobile is redefining mobile connectivity. The upcoming third-party app data support and official T-Satellite launch mark a significant step toward seamless communication, positioning T-Mobile as a trailblazer in next-generation wireless services.

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoTesla debuts hands-free Grok AI with update 2025.26: What you need to know

-

Elon Musk1 week ago

Elon Musk1 week agoElon Musk confirms Grok 4 launch on July 9 with livestream event

-

Elon Musk5 days ago

Elon Musk5 days agoxAI launches Grok 4 with new $300/month SuperGrok Heavy subscription

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoTesla Model 3 ranks as the safest new car in Europe for 2025, per Euro NCAP tests

-

Elon Musk2 weeks ago

Elon Musk2 weeks agoxAI’s Memphis data center receives air permit despite community criticism

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoTesla begins Robotaxi certification push in Arizona: report

-

Elon Musk2 weeks ago

Elon Musk2 weeks agoTesla reveals it is using AI to make factories more sustainable: here’s how

-

Elon Musk2 weeks ago

Elon Musk2 weeks agoTesla scrambles after Musk sidekick exit, CEO takes over sales