News

SpaceX President breaks silence on rumored Zuma mission failure

After some 24 hours of total silence from all parties involved, dubious rumors began to trickle out on the afternoon of January 8 suggesting that SpaceX’s launch of Northrop Grumman’s highly secretive Zuma payload had somehow failed. Without hesitation, otherwise reputable outlets like CNBC and the Wall Street Journal immediately published separate articles claiming that lawmakers had been updated about the mission and told that the satellite had been destroyed while reentering Earth’s atmosphere. Having completely failed to both make it to orbit and “perfectly” separate from SpaceX’s Falcon 9 second stage, these articles implicitly placed the blame on SpaceX.

Claims of Zuma’s failure to properly separate from the second stage of the rocket led immediately to suggestions that SpaceX was at fault. The satellite’s manufacturer, Northrop Grumman, also refused to comment due to the classified nature of the mission, and the company may well have had their hands tied by requirements of secrecy from their customer(s). Immediately following these quick revelations, SpaceX was understandably bombarded with requests for comment by the media and furnished a response that further acknowledged the off-limits secrecy of the mission. However, SpaceX also stated that the company’s available data showed that Falcon 9 completed the mission without fault.

Falcon 9 1043 and its Zuma payload are ready for launch once again, this time from the brand-new LC-40 pad. (Tom Cross/Teslarati)

Without any background knowledge of spaceflight, this flurry of reporting and corporate comments would seem to be perfectly reasonable and unsurprising. However, the barest application of simple logic and orbital mechanics (what is actually involved in launching satellites to orbit) would have almost completely invalidated the information purportedly given to them.

Around the same time as claims of complete failure and satellite reentry were published, amateur spy satellite trackers had already begun the routine task of tracking and cataloging Zuma’s launch and orbit. Following Ars Technica’s breaking (and thankfully even-keeled) article on whispers of failure, reputable journalist Peter B. de Selding corroborated the rumors with reports that Zuma could be dead in orbit after separation from SpaceX’s upper stage. These facts alone ought to have stopped dead any speculation that Zuma had reentered while still attached to the Falcon 9 upper stage, and this was strengthened further by Dr. Marco Langbroek, who later published images provided to him that with very little doubt showed the second stage in a relatively stable orbit similar to the orbit that might be expected after a nominal launch.

This is the image taken by Dutch pilot Peter Horstink, from his aircraft over Khartoum near 3:15 UT, 2h 15m after launch.

This is probably the Falcon 9 venting fuel.#Zuma pic.twitter.com/EEsl7e1sQP— Dr Marco Langbroek (@Marco_Langbroek) January 8, 2018

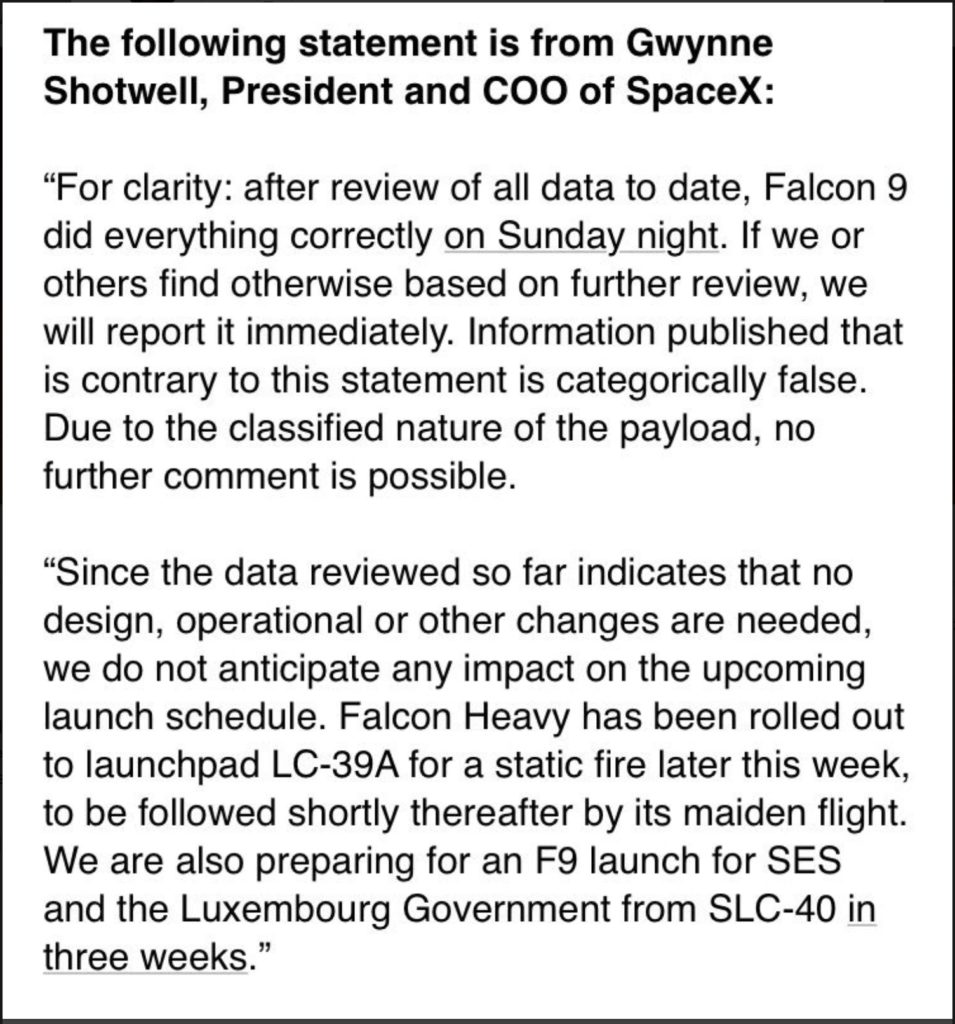

Further complicating claims that the satellite failed to separate, Northrop Grumman had explicitly required that they be allowed to furnish the payload adapter for the Zuma mission, meaning that SpaceX was not responsible for connecting the satellite to the second stage, nor separating it after launch. In other words, if the satellite failed to separate, it would appear that SpaceX could not be easily blamed. However, regardless of these facts, SpaceX’s COO Gwynne Shotwell issued a thoroughly blunt and explicit statement earlier this morning, January 9. In no simple terms, she pegged rumors implicating SpaceX as the source of failure as “categorically false.” More importantly, she reiterated the simple facts that Falcon Heavy’s static fire and launch campaign were proceeding apace, and further stated that an upcoming launch of a communications satellite for SES and the Luxembourg government was also proceeding nominally for a launch around the end of January.

[Source: Chris G via Twitter]

Quite simply, if SpaceX’s hardware had suffered any form of anomaly, let alone issues serious enough to destroy a customer’s payload, all future launches would be immediately and indefinitely postponed, and all customers would be simultaneously notified of Falcon 9’s grounding. The last thing that a launch company would do in such an event is to allow a respected executive blatantly and publicly lie to the media about a long-time customer’s imminent launch date. For satellite communications companies like SES, delayed launches can cause major problems for shareholders and throw a multitude of wrenches into the fiscal gears, as delayed launches cost money on their own. They also delay the point at which any given satellite can begin to generate revenue.

A composite long exposure showing the launch, landing, and second stage burns during the Zuma mission. (Tom Cross/Teslarati)

But wait…

While current information almost unequivocally suggests that SpaceX is in the clear, there has yet to be any official confirmation that the Zuma satellite is in any way dead or has actually failed. This is par for the course of classified government launches, and Zuma’s launch campaign was even more secretive and eccentric than usual – we still have no idea what government agency or agencies are responsible for the mission. And the satellite’s manufacturer was explicitly provided only a few minutes before its launch. Any publication with experience dealing with military topics and news would explicitly understand that any ‘leaked’ information on highly classified topics is inherently untrustworthy and ought to be handled with the utmost rigor and skepticism.

In reality, the most we will ever likely know about these mysterious events will be provided in a handful of weeks by amateur satellite trackers: if they find a new object motionless in the expected orbit, leaks of Zuma’s abject failure will be largely corroborated. If nothing appears in that orbit once the satellite is expected to be visible, it can be reasonably assumed that Zuma reentered the atmosphere at some point, also hinting at a total failure. It can be said with some certainty that if Zuma failed to detach from Falcon 9’s second stage, SpaceX would delay its planned reentry indefinitely until all conceivable attempts to salvage the mission had been analyzed. Observations from pilots and people on the ground suggest without a doubt that the second stage reached a stable orbit, and once in that orbit, reentry could be delayed for weeks or months if the stage was not intentionally deorbited. Dr. Langbroek discusses these possibilities in greater detail in an article posted to his blog.

Ultimately, there are still numerous odd aspects surrounding the launch of Zuma that do not wholly mesh with publicly available information. For example, initial reports about the launch made it clear that the customer had explicitly contracted Zuma’s launch for no later or earlier than November 2017. This was delayed until January after SpaceX reportedly discovered issues with at least one Falcon 9 payload fairing, although the launch of Iridium-4 just over a month later was not delayed, and a replacement fairing was never spotted at Cape Canaveral (not that unusual). Why November 2017, and why delay the launch for nearly two months after that window was missed?

- Falcon 9 B1043 lifts off for the first time with Zuma on January 7. (Tom Cross/Teslarati)

- Falcon 9 lifts off with Zuma on January 7. (Tom Cross/Teslarati)

Of note, anonymous comments on Reddit were also corroborated by Eric Berger of Ars Technica, suggesting that Elon Musk did actually tell SpaceX employees that the launch of Zuma was possibly the most expensive and/or important contract SpaceX had yet to win. This raises a huge number of questions, as the payload was clearly small enough for Falcon 9 to return to Landing Zone-1 for recovery. This caps the mass of Zuma at about that of SpaceX’s Cargo Dragon spacecraft, indeed a fairly hefty capsule at around 10,000 kg, but still far from a satisfying explanation of its apparent value. While it seems unlikely that Zuma alone cost $1 billion or more, as many outlets have been suggesting (assuming?), it might be more reasonable to assume that the potential value of Zuma comes from future missions it might act as a proof of concept for – a highly secretive defense-related satellite constellation, in other words. This, too, slips uncomfortably far into the realm of “crazy government conspiracy theories,” but other explanations are far not forthcoming.

Sadly, the secrecy surrounding Zuma means that the general public will almost certainly remain in the dark for the indefinite future, at least until some future administration chooses to declassify it. The question of whether Zuma failed and whether that failure can be attributed to Northrop Grumman, SpaceX, or some combination of the two will nevertheless be answered imminently by delays or the lack-thereof for SpaceX’s upcoming launch manifest of Falcon Heavy, GovSat-1/SES-16, and PAZ, all scheduled within the next four weeks, give or take.

Elon Musk

Tesla analyst issues stern warning to investors: forget Trump-Musk feud

A Tesla analyst today said that investors should not lose sight of what is truly important in the grand scheme of being a shareholder, and that any near-term drama between CEO Elon Musk and U.S. President Donald Trump should not outshine the progress made by the company.

Gene Munster of Deepwater Management said that Tesla’s progress in autonomy is a much larger influence and a significantly bigger part of the company’s story than any disagreement between political policies.

Munster appeared on CNBC‘s “Closing Bell” yesterday to reiterate this point:

“One thing that is critical for Tesla investors to remember is that what’s going on with the business, with autonomy, the progress that they’re making, albeit early, is much bigger than any feud that is going to happen week-to-week between the President and Elon. So, I understand the reaction, but ultimately, I think that cooler heads will prevail. If they don’t, autonomy is still coming, one way or the other.”

BREAKING: GENE MUNSTER SAYS — $TSLA AUTONOMY IS “MUCH BIGGER” THAN ANY FEUD 👀

He says robotaxis are coming regardless ! pic.twitter.com/ytpPcwUTFy

— TheSonOfWalkley (@TheSonOfWalkley) July 2, 2025

This is a point that other analysts like Dan Ives of Wedbush and Cathie Wood of ARK Invest also made yesterday.

On two occasions over the past month, Musk and President Trump have gotten involved in a very public disagreement over the “Big Beautiful Bill,” which officially passed through the Senate yesterday and is making its way to the House of Representatives.

Musk is upset with the spending in the bill, while President Trump continues to reiterate that the Tesla CEO is only frustrated with the removal of an “EV mandate,” which does not exist federally, nor is it something Musk has expressed any frustration with.

In fact, Musk has pushed back against keeping federal subsidies for EVs, as long as gas and oil subsidies are also removed.

Nevertheless, Ives and Wood both said yesterday that they believe the political hardship between Musk and President Trump will pass because both realize the world is a better place with them on the same team.

Munster’s perspective is that, even though Musk’s feud with President Trump could apply near-term pressure to the stock, the company’s progress in autonomy is an indication that, in the long term, Tesla is set up to succeed.

Tesla launched its Robotaxi platform in Austin on June 22 and is expanding access to more members of the public. Austin residents are now reporting that they have been invited to join the program.

Elon Musk

Tesla surges following better-than-expected delivery report

Tesla saw some positive momentum during trading hours as it reported its deliveries for Q2.

Tesla (NASDAQ: TSLA) surged over four percent on Wednesday morning after the company reported better-than-expected deliveries. It was nearly right on consensus estimations, as Wall Street predicted the company would deliver 385,000 cars in Q2.

Tesla reported that it delivered 384,122 vehicles in Q2. Many, including those inside the Tesla community, were anticipating deliveries in the 340,000 to 360,000 range, while Wall Street seemed to get it just right.

Tesla delivers 384,000 vehicles in Q2 2025, deploys 9.6 GWh in energy storage

Despite Tesla meeting consensus estimations, there were real concerns about what the company would report for Q2.

There were reportedly brief pauses in production at Gigafactory Texas during the quarter and the ramp of the new Model Y configuration across the globe were expected to provide headwinds for the EV maker during the quarter.

At noon on the East Coast, Tesla shares were up about 4.5 percent.

It is expected that Tesla will likely equal the number of deliveries it completed in both of the past two years.

It has hovered at the 1.8 million mark since 2023, and it seems it is right on pace to match that once again. Early last year, Tesla said that annual growth would be “notably lower” than expected due to its development of a new vehicle platform, which will enable more affordable models to be offered to the public.

These cars are expected to be unveiled at some point this year, as Tesla said they were “on track” to be produced in the first half of the year. Tesla has yet to unveil these vehicle designs to the public.

Dan Ives of Wedbush said in a note to investors this morning that the company’s rebound in China in June reflects good things to come, especially given the Model Y and its ramp across the world.

He also said that Musk’s commitment to the company and return from politics played a major role in the company’s performance in Q2:

“If Musk continues to lead and remain in the driver’s seat, we believe Tesla is on a path to an accelerated growth path over the coming years with deliveries expected to ramp in the back-half of 2025 following the Model Y refresh cycle.”

Ives maintained his $500 price target and the ‘Outperform’ rating he held on the stock:

“Tesla’s future is in many ways the brightest it’s ever been in our view given autonomous, FSD, robotics, and many other technology innovations now on the horizon with 90% of the valuation being driven by autonomous and robotics over the coming years but Musk needs to focus on driving Tesla and not putting his political views first. We maintain our OUTPERFORM and $500 PT.”

Moving forward, investors will look to see some gradual growth over the next few quarters. At worst, Tesla should look to match 2023 and 2024 full-year delivery figures, which could be beaten if the automaker can offer those affordable models by the end of the year.

Investor's Corner

Tesla delivers 384,000 vehicles in Q2 2025, deploys 9.6 GWh in energy storage

The quarter’s 9.6 GWh energy storage deployment marks one of Tesla’s highest to date.

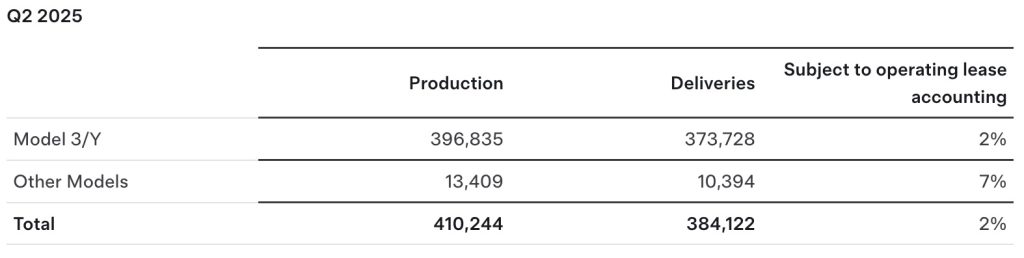

Tesla (NASDAQ: TSLA) has released its Q2 2025 vehicle delivery and production report. As per the report, the company delivered over 384,000 vehicles in the second quarter of 2025, while deploying 9.6 GWh in energy storage. Vehicle production also reached 410,244 units for the quarter.

Model 3/Y dominates output, ahead of earnings call

Of the 410,244 vehicles produced during the quarter, 396,835 were Model 3 and Model Y units, while 13,409 were attributed to Tesla’s other models, which includes the Cybertruck and Model S/X variants. Deliveries followed a similar pattern, with 373,728 Model 3/Ys delivered and 10,394 from other models, totaling 384,122.

The quarter’s 9.6 GWh energy storage deployment marks one of Tesla’s highest to date, signaling continued strength in the Megapack and Powerwall segments.

Year-on-year deliveries edge down, but energy shows resilience

Tesla will share its full Q2 2025 earnings results after the market closes on Wednesday, July 23, 2025, with a live earnings call scheduled for 4:30 p.m. CT / 5:30 p.m. ET. The company will publish its quarterly update at ir.tesla.com, followed by a Q&A webcast featuring company leadership. Executives such as CEO Elon Musk are expected to be in attendance.

Tesla investors are expected to inquire about several of the company’s ongoing projects in the upcoming Q2 2025 earnings call. Expected topics include the new Model Y ramp across the United States, China, and Germany, as well as the ramp of FSD in territories outside the US and China. Questions about the company’s Robotaxi business, as well as the long-referenced but yet to be announced affordable models are also expected.

-

Elon Musk2 days ago

Elon Musk2 days agoTesla investors will be shocked by Jim Cramer’s latest assessment

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoTesla Robotaxi’s biggest challenge seems to be this one thing

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoTesla’s Grok integration will be more realistic with this cool feature

-

Elon Musk2 weeks ago

Elon Musk2 weeks agoElon Musk slams Bloomberg’s shocking xAI cash burn claims

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoTexas lawmakers urge Tesla to delay Austin robotaxi launch to September

-

Elon Musk1 week ago

Elon Musk1 week agoFirst Look at Tesla’s Robotaxi App: features, design, and more

-

Elon Musk2 weeks ago

Elon Musk2 weeks agoTesla Robotaxis are becoming a common sight on Austin’s public roads

-

Elon Musk2 weeks ago

Elon Musk2 weeks agoTesla CEO Elon Musk hits back at drug use claims, calls publications ‘hypocrites’