News

SpaceX’s next commercial Falcon Heavy launch to carry Astranis rideshare satellite

Geostationary satellite communications startup Astranis has decided to move its first operational satellite launch from a SpaceX Falcon 9 to a Falcon Heavy, effectively securing the massive rocket its first commercial rideshare payload.

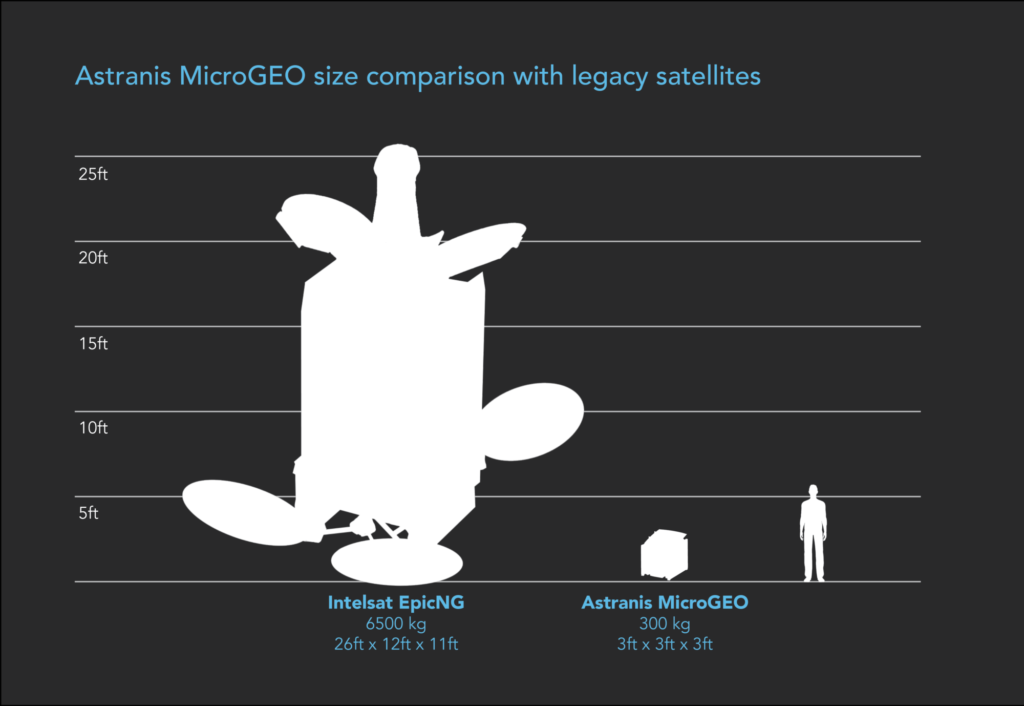

While not technically Falcon Heavy’s first rideshare payload and not the rocket’s first commercial rideshare launch contract, Astranis’ first 400 kg (~900 lb) MicroGEO satellite nevertheless appears set to become the first commercial rideshare payload to actually fly on the world’s largest operational rocket. Not all that dissimilar to Starlink in scope and its desire to disrupt a stagnant industry, Astranis wants to offer global communications services providers a different route to geostationary internet and broadcast solutions. Unlike SpaceX’s constellation, the startup’s MicroGEO satellites are designed for geostationary orbits ~36,000 km (~22,200 mi) above Earth’s surface and more than 60 times higher than Starlink.

However, like Starlink satellites, MicroGEO will feature exceptional density (throughput per kilogram), weighing a magnitude less than average modern geostationary communications satellites while still offering up to 10 Gbps of bandwidth. Expected to cost around $40M apiece compared to ~$100M+ for most traditional offerings, the value proposition of small Astranis satellites with 5-10 times less bandwidth admittedly gets a bit blurrier, but the company should still offer a viable alternative for companies and countries that just don’t need a massive satellite.

For example, Astranis’ first customer and the buyer behind the first MicroGEO satellite – known as Aurora 4A – is Pacific Dataport, a company focused on delivering connectivity throughout Alaska – one of the most remote and sparsely populated places on Earth. That combination of attributes makes providing broadband communication services spectacularly difficult and satellite internet the perfect (and, to an extent, the only viable) solution. However, a full $100M+ geostationary communications satellite with 50-100+ Gbps of bandwidth would likely far outweigh the needs of Alaska’s ~730,000 residents – especially when most Alaskans live in the state’s few large cities, most of which already have passable internet connectivity.

As such, it’s easy to see why a small but high-performance geostationary satellite like the kind Astranis offers might be a perfect fit for an Alaskan internet provider. While low Earth orbit (LEO) constellations like OneWeb and SpaceX’s Starlink do offer far more bandwidth and a user experience potentially as good or better than a wired connection almost anywhere on Earth, both companies first have to launch hundreds or thousands of satellites to ensure continuous coverage. Both Starlink and OneWeb are a ways away from offering continuous coverage in polar regions.

Geostationary satellites – especially those as small as Aurora 4A – offer a significant shortcut, requiring just a single satellite and ground stations in one or a few very specific regions to fully complete a communications network. Of course, thanks to universal limits posed by the speed of light, geostationary internet customers end up saddled with extreme latency (ping on the order of 300-1000ms) and strict individual bandwidth limits. But in places like Alaska, where there can easily be no alternative for the most rural residents, Astranis – or just about anything – could bring welcome relief.

Now, Astranis says it has moved the first MicroGEO satellite from a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket to rideshare payload on Falcon Heavy’s upcoming ViaSat-3 launch, scheduled no earlier than Q2 2022. According to the startup, doing so will allow the tiny satellite to begin operations over Alaska mere days or a few weeks after launch, saving months of orbit-raising thanks to Falcon Heavy’s performance. That’s only possible because, as the Astranis press release also revealed, Falcon Heavy is scheduled to launch the 6.4 ton (~14,100 lb) ViaSat-3 and 400 kg (~900 lb) Aurora 4A satellites directly to geostationary orbit (GEO). If Falcon Heavy’s upcoming USSF-44 mission launches on schedule next month, ViaSat-3 will be SpaceX’s second direct-to-GEO mission ever and the company’s first for a commercial customer.

Assuming SpaceX is still able to recover two – or even all three – of Falcon Heavy’s side boosters while launching almost 7 tons (~15,500 lb) of satellites directly to GEO, it will also demonstrate just how much of a force to be reckoned with it really is, well and truly leaving competitors ULA and Arianespace with nowhere to hide on the open market.

Elon Musk

Tesla investors will be shocked by Jim Cramer’s latest assessment

Jim Cramer is now speaking positively about Tesla, especially in terms of its Robotaxi performance and its perception as a company.

Tesla investors will be shocked by analyst Jim Cramer’s latest assessment of the company.

When it comes to Tesla analysts, many of them are consistent. The bulls usually stay the bulls, and the bears usually stay the bears. The notable analysts on each side are Dan Ives and Adam Jonas for the bulls, and Gordon Johnson for the bears.

Jim Cramer is one analyst who does not necessarily fit this mold. Cramer, who hosts CNBC’s Mad Money, has switched his opinion on Tesla stock (NASDAQ: TSLA) many times.

He has been bullish, like he was when he said the stock was a “sleeping giant” two years ago, and he has been bearish, like he was when he said there was “nothing magnificent” about the company just a few months ago.

Now, he is back to being a bull.

Cramer’s comments were related to two key points: how NVIDIA CEO Jensen Huang describes Tesla after working closely with the Company through their transactions, and how it is not a car company, as well as the recent launch of the Robotaxi fleet.

Jensen Huang’s Tesla Narrative

Cramer says that the narrative on quarterly and annual deliveries is overblown, and those who continue to worry about Tesla’s performance on that metric are misled.

“It’s not a car company,” he said.

He went on to say that people like Huang speak highly of Tesla, and that should be enough to deter any true skepticism:

“I believe what Musk says cause Musk is working with Jensen and Jensen’s telling me what’s happening on the other side is pretty amazing.”

Tesla self-driving development gets huge compliment from NVIDIA CEO

Robotaxi Launch

Many media outlets are being extremely negative regarding the early rollout of Tesla’s Robotaxi platform in Austin, Texas.

There have been a handful of small issues, but nothing significant. Cramer says that humans make mistakes in vehicles too, yet, when Tesla’s test phase of the Robotaxi does it, it’s front page news and needs to be magnified.

He said:

“Look, I mean, drivers make mistakes all the time. Why should we hold Tesla to a standard where there can be no mistakes?”

It’s refreshing to hear Cramer speak logically about the Robotaxi fleet, as Tesla has taken every measure to ensure there are no mishaps. There are safety monitors in the passenger seat, and the area of travel is limited, confined to a small number of people.

Tesla is still improving and hopes to remove teleoperators and safety monitors slowly, as CEO Elon Musk said more freedom could be granted within one or two months.

News

Tesla launches ultra-fast V4 Superchargers in China for the first time

Tesla has V4 Superchargers rolling out in China for the first time.

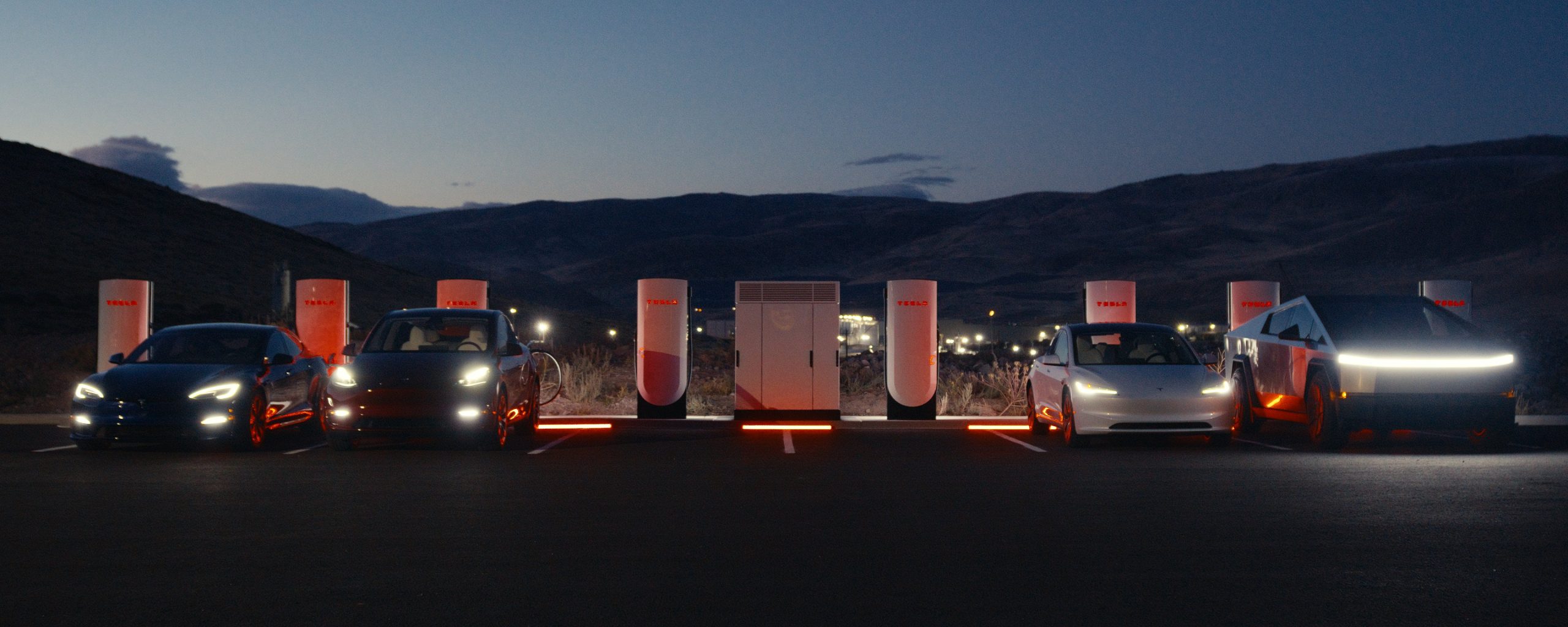

Tesla already has nearly 12,000 Supercharger piles across mainland China. However, the company just initiated the rollout of the ultra-fast V4 Superchargers in China for the first time, bringing its quick-charging piles to the country for the first time since their launch last year.

The first batch of V4 Superchargers is now officially up and running in China, the company announced in a post on Chinese social media outlet Weibo today.

The company said in the post:

“The first batch of Tesla V4 Superchargers are online. Covering more service areas, high-speed charging is more convenient, and six-layer powerful protection such as rain and waterproof makes charging very safe. Simultaneously open to non-Tesla vehicles, and other brands of vehicles can also be charged. There are more than 70,000 Tesla Superchargers worldwide. The charging network layout covers 100% of the provincial capitals and municipalities in mainland China. More V4 Superchargers will be put into use across the country. Optimize the charging experience and improve energy replenishment efficiency. Tesla will accompany you to the mountains, rivers, lakes, and seas with pure electricity!”

The first V4 Superchargers Tesla installed in China are available in four cities across the country: Shanghai, Zhejiang, Gansu, and Chongqing.

Credit: Tesla China

Tesla has over 70,000 Superchargers worldwide. It is the most expansive and robust EV charging network in the world. It’s the main reason why so many companies have chosen to adopt Tesla’s charging connector in North America and Europe.

In China, some EVs can use Tesla Superchargers as well.

The V4 Supercharger is capable of charging vehicles at speeds of up to 325kW for vehicles in North America. This equates to over 1,000 miles per hour of charging.

Elon Musk

Elon Musk hints at when Tesla could reduce Safety Monitors from Robotaxi

Tesla could be reducing Safety Monitors from Robotaxi within ‘a month or two,’ CEO Elon Musk says.

Elon Musk hinted at when Tesla could begin reducing Safety Monitors from its Robotaxis. Safety Monitors are Tesla employees who sit in the front passenger seat during the driverless rides, and are there to ensure safety for occupants during the earliest rides.

Tesla launched its Robotaxi fleet in Austin last Sunday, and after eight days, videos and reviews from those who have ridden in the driverless vehicles have shown that the suite is safe, accurate, and well coordinated. However, there have been a few hiccups, but nothing that has put anyone’s safety in danger.

A vast majority — close to all of the rides — at least according to those who have ridden in the Robotaxi, have been performed without any real need for human intervention. We reported on what was the first intervention last week, as a Safety Monitor had to step in and stop the vehicle in a strange interaction with a UPS truck.

Watch the first true Tesla Robotaxi intervention by safety monitor

The Tesla and UPS delivery truck were going for the same street parking space, and the Tesla began to turn into it. The UPS driver parallel parked into the spot, which was much smaller than his truck. It seemed to be more of an instance of human error instead of the Robotaxi making the wrong move. This is something that the driverless cars will have to deal with because humans are aggressive and sometimes make moves they should not.

The Safety Monitors have not been too active in the vehicles. After all, we’ve only seen that single instance of an intervention. There was also an issue with the sun, when the Tesla braked abnormally due to the glare, but this was an instance where the car handled the scenario and proceeded normally.

With the Robotaxi fleet operating impressively, some are wondering when Tesla will begin scaling back both the Safety Monitors and Teleoperators that it is using to ensure safety with these early rides.

CEO Elon Musk answered the inquiry by stating, “As soon as we feel it is safe to do so. Probably within a month or two.”

As soon as we feel it is safe to do so.

Probably within a month or two. We continue to improve the Tesla AI with each mile driven.

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) June 30, 2025

Musk’s response seems to confirm that there will be fewer Teleoperators and Safety Monitors in the coming months, but there will still be some within the fleet to ensure safety. Eventually, that number will get to zero.

Reaching a point where Tesla’s Robotaxi is driverless will be another significant milestone for the company and its path to fully autonomous ride-sharing.

Eventually, Tesla will roll out these capabilities to consumer-owned vehicles, offering them a path to generate revenue as their car operates autonomously and completes rides.

For now, Tesla is focusing on perfecting the area of Austin where it is currently offering driverless rides for just $4.20 to a small group of people.

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoTesla Robotaxi’s biggest challenge seems to be this one thing

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoTesla confirms massive hardware change for autonomy improvement

-

Elon Musk2 weeks ago

Elon Musk2 weeks agoElon Musk slams Bloomberg’s shocking xAI cash burn claims

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoTesla China roars back with highest vehicle registrations this Q2 so far

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoTesla features used to flunk 16-year-old’s driver license test

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoTesla dominates Cars.com’s Made in America Index with clean sweep

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoTexas lawmakers urge Tesla to delay Austin robotaxi launch to September

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoTesla’s Grok integration will be more realistic with this cool feature