SpaceX

How does SpaceX measure up to other Mars-destined challengers? [Countdown to Mars, Part 1]

SpaceX isn’t the only organization with eyes set on the skies of Mars. There are other dreamers with their own plans and technology. How does SpaceX measure up?

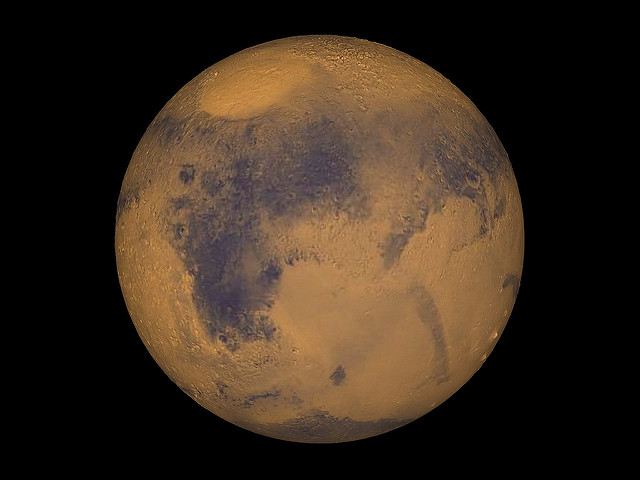

If it wasn’t entirely clear before, it is now with all the recent announcements from SpaceX: Elon Musk said “Mars”, and he really meant Mars. While Falcon 9 hits milestone after milestone, SpaceX inches closer and closer to “boots on the ground” in red, Martian regolith.

SpaceX isn’t the only organization with eyes set on Martian skies, however. There are other dreamers with their own plans and technology, NASA being a “given” of course. After all, if we’re going to Mars, it’s natural to expect the agency that sent humans to the moon to have something to say about sending humans to another planetary body.

Who all is planning on going to Mars?

To be clear, the Mars planners I’m referring to here are developing full missions for human transport, not just robotics. Further, I’m narrowing the criteria to only include those actively developing the technology rather than working on related scientific studies, developing artistic concepts, engineering helpful devices, and so forth.

In that light, it seems the field thus far consists of two other major players besides SpaceX.

NASA

Aptly named, NASA’s “Journey to Mars” program consists of developing all the capabilities needed to achieve what its designation implies. Their vision comprises the development of their next generation rocket, the Space Launch System, coupled with a crew capsule called Orion.

The Space Launch System has three primary components: One main core and two solid rocket boosters, most components being either derived or upgraded from space shuttle technology. The plan is to “evolve” the configurations through three “blocks”, the third of which will be capable of handling all of the payload needs for a mission to Mars.

The Orion capsule, nicknamed “Apollo on steroids”, is very similar to the capsules used in the Apollo programs, but with significant upgrades such as the heat shield that must handle higher reentry speeds. Further, it will house up to four astronauts (one more than Apollo) while supported by a service module, i.e., a connected structure that will provide resources such as power and oxygen. Overall, it’s about three feet wider than the Apollo capsules, an expansion which translates into a much roomier space square-footage wise.

Somewhere in NASA’s mix is an Asteroid Redirect Mission that involves capturing an asteroid, bringing it into orbit around the moon, and sending crews there to land and study it. Don’t see how that’s really related to Mars? Neither do I, but it’s included on all the “Journey to Mars” posters so it must be. I think I’ve heard people try and explain why the moon wouldn’t suffice for any Mars-related training as well, but I’m personally not convinced enough to really cite the argument. I’m not alone in that confusion, either.

Personally, I’d prefer the pure scientific study of an asteroid to be the justification for the mission, or maybe even “practice” for a future Armageddon event, but when everyone is drumming for Mars, I guess you do what you can. I’ve read that NASA attempted to market it as both of those, but the attempts weren’t successful.

Oh, wait. They changed “asteroid” to “large boulder on an asteroid”. I wonder why? Some of their pages are still citing the original mission… Perhaps it was always either/or?

Speaking of that poster, there’s a space habitat and Mars transfer craft listed, but no other details are provided. NASA’s political and budgetary constraints seem to be limiting any details about how they plan on getting to Mars (landing in particular) once SLS and Orion are flying. These types of restrictions are the reason NASA even has other contenders for the mission, although those same challengers are the ones pushing the journey into the public drumming in the first place.

Mars One

Mars One is a non-profit foundation which hopes to send astronauts they select and train through an in-house application process to Mars via technology they will pay to have built and launched using current service providers.

Founded by Dutch scientist-entrepreneurs Bas Lansdorp and Arno Wielders in 2011, Mars One is an unusual player in the Mars transport game. It is not an aerospace company, as all systems are designed and built by outsourced companies, and their planned sources of funding are private investment and the creation of a reality show documenting the astronauts’ mission from training through their first steps on Mars (although they’ve had some recent troubles with that). Mars One would also like you to purchase plenty of merchandise in the meantime to support their efforts and have even set up a “point” system to encourage this.

For their astronauts, the company solicited applications from would-be space travelers around the world via the Internet, received about two hundred thousand responses, and is now in the process of narrowing down their candidate field to a maximum of twenty-four hopefuls (six groups of four, specifically) that will train together for the next ten years before groups are shuttled off to Mars every two years.

Mars One also plans on having their entire human habitat set up by rovers prior to the first astronaut arrivals, meaning there will be several cargo missions to the surface in the lead-up years. Their first unmanned mission is planned for 2020 wherein some tech will be put to the test along with placing a communications satellite in orbit. Then, a rover and second communications satellite is planned for 2022, followed by cargo missions in 2024 to have the habitat fully operational by 2025 in advance of the first crew arrival in 2027.

Oh, by the way, their trip to Mars will be one-way. According to them, it’s a strategic choice, not a matter of insurance liability for guaranteeing return.

While all space-going organizations face criticism in one way or another, the criticism lodged at Mars One is fairly significant, some even labeling the mission as a scam. To be fair, the nature of their mission combined with the lack of government backing or a billionaire founder puts them in the position that demands fundraising to be a primary activity. Add to that an estimated mission cost of six billion dollars and skepticism quickly rises. Everything involved becomes subject to close analysis.

Their plans aren’t impossible, of course, just full of challenges without perceivable solutions. I don’t personally believe the mission is a scam, and I don’t doubt its long-term viability should the astronauts actually make it to Mars; I think they won’t be the only crews visiting the planet come the days when their intentions match their funding needs, therefore a “back up” plan is essentially built-in. However, I also see a ten-year mission plan that is placing a lot of faith in contract work that is supposed to produce what SpaceX is still working on fourteen years after-the-fact and with a much better financial portfolio.

Honorable Mention: “Mars Direct” by The Mars Society

Founded in 1998 by Dr. Robert Zubrin (and “others”), The Mars Society has made humans on Mars their business for a very long time. Since they are not an organization primarily developing & building technology to go to Mars, I have to classify them as “honorable mention”; however, their contributions to the effort should definitely be noted. Elon Musk certainly has.

Dr. Zubrin of The Mars Society introduces Elon Musk. (Credit: Chris Radcliff under CC by SA-2.0.)

“Mars Direct” is The Mars Society’s detailed plan for putting humans on Mars and, like Mars One, it focuses on building components using existing technology to achieve orbit and landing rather than depending on future developments. It advocates a “live off the land” approach that minimizes cargo needs.

The Mars Direct mission would comprise two phases. First, using a heavy lift launch vehicle, a fuel generation structure would be sent to the Martian surface to generate a Methane/Oxygen bipropellant for a return trip and to power equipment. Second, another fuel generation structure plus a crew and habitat would be sent and landed near the first structure. While in orbit, the effects of zero gravity would be mitigated by rotation of the crew vehicle via a tether connected to the spent upper stage of the transport rocket to act as an anchor. The crew missions would necessarily require a two-year length due to the orbital proximities of Earth and Mars combined with the six-month travel time each way.

Unlike Mars One, this plan has been developed with incredible detail and was published in 1991 by Dr. Zubrin, David A. Baker, and Owen Gwynne. The Mars Society also has annual conferences (this year’s will be the 19th one) which both flesh out the plan’s details and feature speakers across the aerospace spectrum discussing the various aspects. Dr. Zubrin’s book, The Case for Mars, fleshes out the plan in a more readable format, and there’s also plenty of good stuff on the Mars One website.

SpaceX’s Plan for Mars

The founding goal of SpaceX was, and still is, making humans a multiplanet species. Therefore, no incredibly detailed introduction or lengthy explanation is really needed for them when discussing companies interested in going to Mars (see: publicity). However, for the sake of being thorough (and for the sake of sake’s sake), let’s review the Musk brand for Mars.

Known for its Falcon rocket series (along with its famous founder), SpaceX isn’t hitching a ride to Mars as is Mars One, thereby avoiding the potential pitfall of being “all dressed up with nowhere to go”. They’re building their own ride: The Falcon Heavy.

Scheduled for a test launch this November, the Falcon Heavy will be the most powerful rocket in operation since the Saturn V was used for the Apollo moon program. With three cores powered by nine Merlin engines each, Falcon Heavy will be able to haul around 120,000 pounds to low earth orbit (LEO), 50,000 pounds to geostationary transfer orbit (GTO), and 30,000 pounds of payload to Mars. Just for fun, SpaceX’s website also cites a 6,400 pound payload capacity for trips to Pluto.

SpaceX is also developing their own crew capsule, the Dragon (“Red Dragon” when on its way to Mars), which will include a propulsive landing system (i.e., it can hover) via its eight SuperDraco engines. The landing system also doubles as an emergency escape system in the event that there’s a problem during launch, and while space traveling, Dragon will be supported by a “trunk” (essentially with the same function as Orion’s service module) to support missions as needed.

SpaceX is also developing their own crew capsule, the Dragon (“Red Dragon” when on its way to Mars), which will include a propulsive landing system (i.e., it can hover) via its eight SuperDraco engines. The landing system also doubles as an emergency escape system in the event that there’s a problem during launch, and while space traveling, Dragon will be supported by a “trunk” (essentially with the same function as Orion’s service module) to support missions as needed.

Now, pardon my excitement, but these things are really cool. The SuperDraco engines are doubled up and self-contained, meaning that the lander can lose up to half its engines and still land safely, and if anything goes wrong with one engine, it’s isolated to not impact the others. The engines are also 3D-printed out of Inconel, a high performance nickel-based super alloy.

Bonus level! SpaceX’s long-terms plans don’t just include short(ish) jaunts to Mars and back, although, unlike Mars One, there will be an option to return to Earth via regular cargo missions. There also may be an option with their up and coming Mars Colonial Transport vehicle.

The Mars Colonial Transporter is, at the moment, a mysterious development SpaceX is working on to achieve its goal of large-scale Martian colonization. There’s plenty of speculation about the details, but officially, even the size is being kept secret for now. Elon will only reveal it to be “So big.” A few details were shared (or speculations confirmed) during a Reddit “Ask Me Anything “ (AMA) session this past January such as:

- The second stage could be reusable

- The architecture will be completely different from the Falcon/Dragon system

- The goal payload capacity is 100 metric tons

- There is a family of methane-based engines called “Raptor” being developed by SpaceX for travel to and exploration of Mars.*

*Note: This detail wasn’t particularly new to the AMA, but there aren’t many original sources where Elon or a SpaceX executive has spoken directly about it, thus I’ve included it.

Overall, it certainly seems like SpaceX is charging ahead compared to the others that are aimed for Mars, but it’s not because of their publicity wins. Their steady march via the piece by piece development of the required technology combined with the customer-driven financial viability of the company as a rocket launch provider are key to the believably that they will actually make Mars “happen”.

Coming Up on Countdown to Mars…

SpaceX’s colonial “grand plan” reveal is what I’m counting down to with this “Countdown to Mars” article series. Scheduled for September 26th – 30th of this year, Elon Musk has stated that he will be announcing detailed plans for their Mars Colonial Transporter at the International Astronautical Conference in Guadalajara, Mexico. It’s supposed to be so awesome, even Elon can hardly contain himself. To say that I’m incredibly excited as well would be a huge understatement. So I won’t. I’ll just keep writing about things related to it!

SpaceX’s colonial “grand plan” reveal is what I’m counting down to with this “Countdown to Mars” article series. Scheduled for September 26th – 30th of this year, Elon Musk has stated that he will be announcing detailed plans for their Mars Colonial Transporter at the International Astronautical Conference in Guadalajara, Mexico. It’s supposed to be so awesome, even Elon can hardly contain himself. To say that I’m incredibly excited as well would be a huge understatement. So I won’t. I’ll just keep writing about things related to it!

Coming up on “Countdown to Mars”…

How do these companies plan on solving some of the biggest challenges for achieving a successful mission to Mars? Then, if we are talking about permanent settlements on Mars, what will the human power structure look like? Or in other words, what kind of government will the first human Martians have?

Stay tuned!

News

SpaceX launches Ax-4 mission to the ISS with international crew

The SpaceX Falcon 9 launched Axiom’s Ax-4 mission to ISS. Ax-4 crew will conduct 60+ science experiments during a 14-day stay on the ISS.

SpaceX launched the Falcon 9 rocket kickstarting Axiom Space’s Ax-4 mission to the International Space Station (ISS). Axiom’s Ax-4 mission is led by a historic international crew and lifted off from Kennedy Space Center’s Launch Complex 39A at 2:31 a.m. ET on June 25, 2025.

The Ax-4 crew is set to dock with the ISS around 7 a.m. ET on Thursday, June 26, 2025. Axiom Space, a Houston-based commercial space company, coordinated the mission with SpaceX for transportation and NASA for ISS access, with support from the European Space Agency and the astronauts’ governments.

The Ax-4 mission marks a milestone in global space collaboration. The Ax-4 crew, commanded by U.S. astronaut Peggy Whitson, includes Shubhanshu Shukla from India as the pilot, alongside mission specialists Sławosz Uznański-Wiśniewski from Poland and Tibor Kapu from Hungary.

“The trip marks the return to human spaceflight for those countries — their first government-sponsored flights in more than 40 years,” Axiom noted.

Shukla’s participation aligns with India’s Gaganyaan program planned for 2027. He is the first Indian astronaut to visit the ISS since Rakesh Sharma in 1984.

Axiom’s Ax-4 mission marks SpaceX’s 18th human spaceflight. The mission employs a Crew Dragon capsule atop a Falcon 9 rocket, designed with a launch escape system and “two-fault tolerant” for enhanced safety. The Axiom mission faced a few delays due to weather, a Falcon 9 leak, and an ISS Zvezda module leak investigation by NASA and Roscosmos before the recent successful launch.

As the crew prepares to execute its scientific objectives, SpaceX’s Ax-4 mission paves the way for a new era of inclusive space research, inspiring future generations and solidifying collaborative ties in the cosmos. During the Ax-4 crew’s 14-day stay in the ISS, the astronauts will conduct nearly 60 experiments.

“We’ll be conducting research that spans biology, material, and physical sciences as well as technology demonstrations,” said Whitson. “We’ll also be engaging with students around the world, sharing our experience and inspiring the next generation of explorers.”

SpaceX’s Ax-4 mission highlights Axiom’s role in advancing commercial spaceflight and fostering international partnerships. The mission strengthens global space exploration efforts by enabling historic spaceflight returns for India, Poland, and Hungary.

News

Starlink Cellular’s T-Mobile service to grow with third-party app data

From Oct 2025, T-Satellite will enable third-party apps in dead zones! WhatsApp, X, AccuWeather + more coming soon.

Starlink Cellular’s T-Mobile service will expand with third-party app data support starting in October, enhancing connectivity in cellular dead zones.

T-Mobile’s T-Satellite, supported by Starlink, launches officially on July 23. Following its launch, T-Mobile’s Starlink Cellular service will enable data access for third-party apps like WhatsApp, X, Google, Apple, AccuWeather, and AllTrails on October 1, 2025.

T-Mobile’s Starlink Cellular is currently in free beta. T-Satellite will add MMS support for Android phones on July 23, with iPhone support to follow. MMS support allows users to send images and audio clips alongside texts. By October, T-Mobile will extend emergency texting to all mobile users with compatible phones, beyond just T-Mobile customers, building on its existing 911 texting capability. The carrier also provides developer tools to help app makers integrate their software with T-Satellite’s data service, with plans to grow the supported app list.

T-Mobile announced these updates during an event celebrating an Ookla award naming it the best U.S. phone network, a remarkable turnaround from its last-place ranking a decade ago.

“We not only dream about going from worst to best, we actually do it. We’re a good two years ahead of Verizon and AT&T, and I believe that lead is going to grow,” said T-Mobile’s Chief Operating Officer Srini Gopalan.

T-Mobile unveiled two promotions for its Starlink Cellular services to attract new subscribers. A free DoorDash DashPass membership, valued at $10/month, will be included with popular plans like Experience Beyond and Experience More, offering reduced delivery and service fees. Meanwhile, the Easy Upgrade promotion targets Verizon customers by paying off their phone balances and providing flagship devices like the iPhone 16, Galaxy S25, or Pixel 9.

T-Mobile’s collaboration with SpaceX’s Starlink Cellular leverages orbiting satellites to deliver connectivity where traditional networks fail, particularly in remote areas. Supporting third-party apps underscores T-Mobile’s commitment to enhancing user experiences through innovative partnerships. As T-Satellite’s capabilities grow, including broader app integration and emergency access, T-Mobile is poised to strengthen its lead in the U.S. wireless market.

By combining Starlink’s satellite technology with strategic promotions, T-Mobile is redefining mobile connectivity. The upcoming third-party app data support and official T-Satellite launch mark a significant step toward seamless communication, positioning T-Mobile as a trailblazer in next-generation wireless services.

News

Starlink expansion into Vietnam targets the healthcare sector

Starlink aims to deliver reliable internet to Vietnam’s remote clinics, enabling telehealth and data sharing.

SpaceX’s Starlink expansion into Vietnam targets its healthcare sector. Through Starlink, SpaceX seeks to drive digital transformation in Vietnam.

On June 18, a SpaceX delegation met with Vietnam’s Ministry of Health (MoH) in Hanoi. SpaceX’s delegation was led by Andrew Matlock, Director of Enterprise Sales, and the discussions focused on enhancing connectivity for hospitals and clinics in Vietnam’s remote areas.

Deputy Minister of Health (MoH) Tran Van Thuan emphasized collaboration between SpaceX and Vietnam. Tran stated: “SpaceX should cooperate with the MoH to ensure all hospitals and clinics in remote areas are connected to the StarLink satellite system and share information, plans, and the issues discussed by members of the MoH. The ministry is also ready to provide information and send staff to work with the corporation.”

The MoH assigned its Department of Science, Technology, and Training to work with SpaceX. Starlink Vietnam will also receive support from Vietnam’s Department of International Cooperation. Starlink Vietnam’s agenda includes improving internet connectivity for remote healthcare facilities, developing digital infrastructure for health examinations and remote consultations, and enhancing operational systems.

Vietnam’s health sector is prioritizing IT and digital transformation, focusing on electronic health records, data centers, and remote medical services. However, challenges persist in deploying IT solutions in remote regions, prompting Vietnam to seek partnerships like SpaceX’s.

SpaceX’s Starlink has a proven track record in healthcare. In Rwanda, its services supported 40 health centers, earning praise for improving operations. Similarly, Starlink enabled remote consultations at the UAE’s Emirati field hospital in Gaza, streamlining communication for complex medical cases. These successes highlight Starlink’s potential to transform Vietnam’s healthcare landscape.

On May 20, SpaceX met with Vietnam’s Ministry of Industry and Trade, announcing a $1.5 billion investment to provide broadband internet, particularly in remote, border, and island areas. The first phase includes building 10-15 ground stations across the country. This infrastructure will support Starlink’s healthcare initiatives by ensuring reliable connectivity.

Starlink’s expansion in Vietnam aligns with the country’s push for digital transformation, as outlined by the MoH. By leveraging its satellite internet expertise, SpaceX aims to bridge connectivity gaps, enabling advanced healthcare services in underserved regions. This collaboration could redefine Vietnam’s healthcare infrastructure, positioning Starlink as a key player in the nation’s digital future.

-

Elon Musk3 days ago

Elon Musk3 days agoTesla investors will be shocked by Jim Cramer’s latest assessment

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoTesla Robotaxi’s biggest challenge seems to be this one thing

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoTexas lawmakers urge Tesla to delay Austin robotaxi launch to September

-

Elon Musk2 weeks ago

Elon Musk2 weeks agoFirst Look at Tesla’s Robotaxi App: features, design, and more

-

Elon Musk2 weeks ago

Elon Musk2 weeks agoxAI’s Grok 3 partners with Oracle Cloud for corporate AI innovation

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoSpaceX and Elon Musk share insights on Starship Ship 36’s RUD

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoWatch Tesla’s first driverless public Robotaxi rides in Texas

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoTesla has started rolling out initial round of Robotaxi invites