SpaceX

SpaceX builds new orbital Starship sections as Starhopper loses its engine

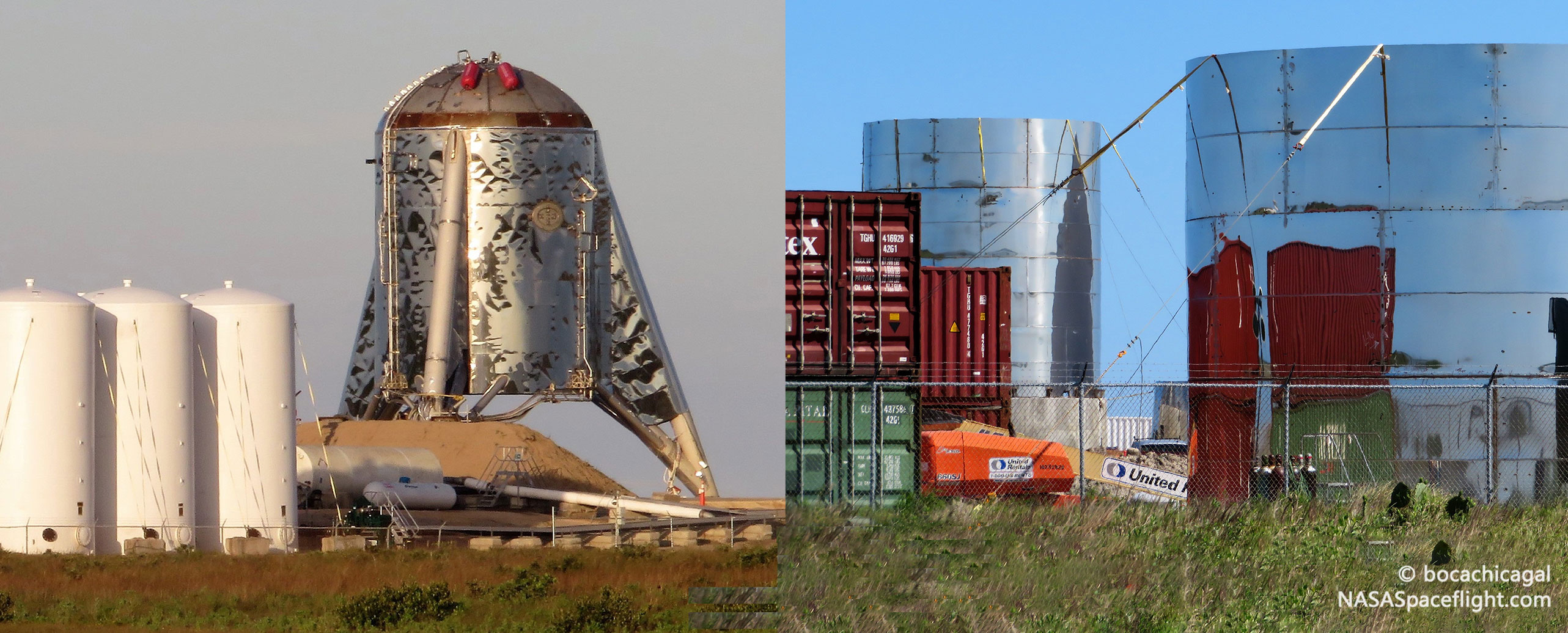

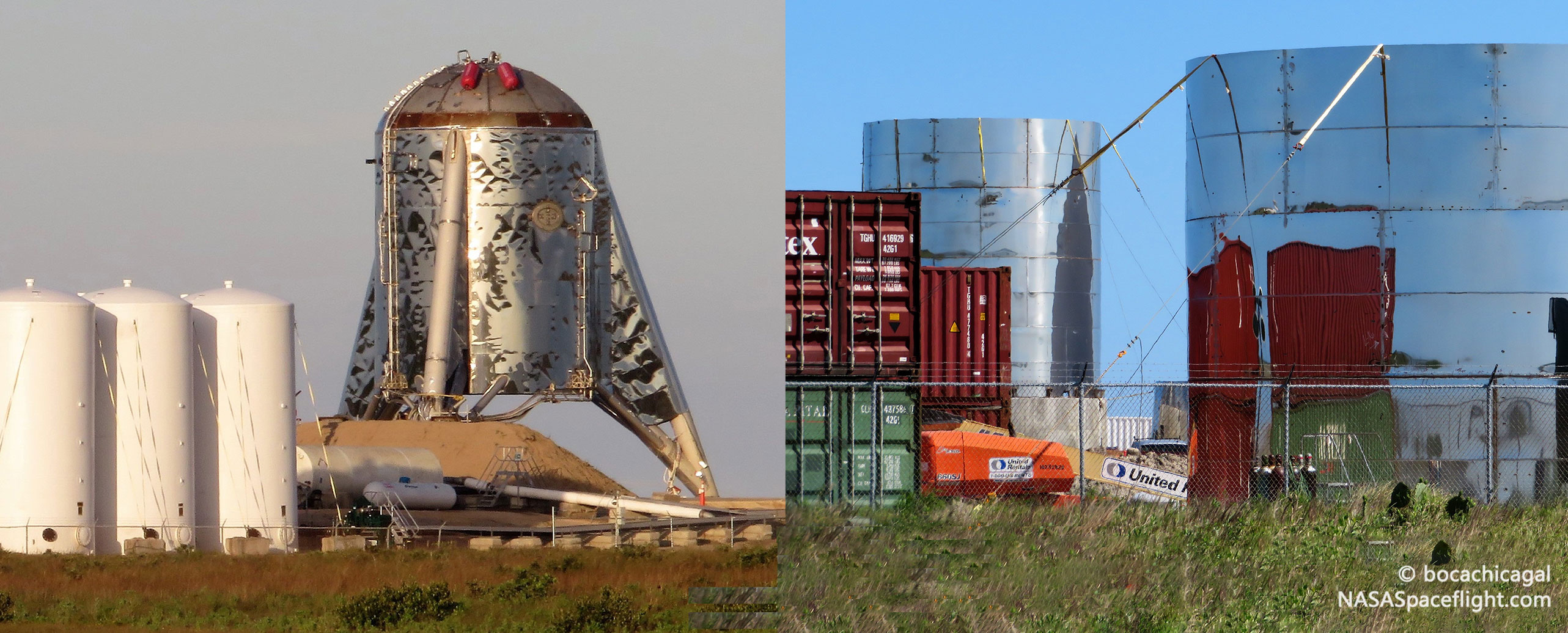

Amidst the growing buzz centered around the imminent second launch of Falcon Heavy, SpaceX’s South Texas team has continued to work on Starhopper and the first orbital Starship prototype. wrapping up the first major tests of the former and making new progress on the latter’s aeroshell.

For unknown reasons, SpaceX technicians uninstalled Starhopper’s Raptor – the second full-scale engine ever built – shortly after the vehicle’s first true hop test and proceeded to package it up for shipment elsewhere, likely McGregor’s test facilities or the Hawthorne factory. Simultaneously, the third completed Raptor (SN03) was recently installed in McGregor according to photos and observations published by NASASpaceflight.com, preparing to continue to the engineering verification tests that began in February. Once those tests are complete and the engine design is modified to account for the lessons learned with Raptor SN01, SpaceX’s next step will be to begin ramping Raptor production in preparation for multi-engine Starhopper testing and – eventually – the completion of the first orbit-capable Starship prototype.

Needless to say, SpaceX is juggling a lot of interconnected projects in an effort to speed its Starship/Super Heavy (formerly BFR) development program, none of which are being discussed by the company in more than a cursory manner. What follows is thus meant to be an informed but speculative estimate of what is currently going on and what is next for BFR.

Starhopper slips the surly bonds

Over the course of the last two weeks, SpaceX has been almost continuously testing the first integrated Starship prototype, a partial-fidelity vehicle known as Starhopper. The testing primarily involved almost a dozen wet dress rehearsals (WDRs) in which the rocket was filled with some quantity of liquid oxygen and methane propellant and helium for pressurization as engineers and technicians worked through several bugs preventing Raptor from safely operating. According to CEO Elon Musk, some form of ice – potentially methane, oxygen, or even water – was forming in or around parts known as “prevalves”, likely referring to valves involved in the process of supply rocket engines with the right amount of fuel and oxidizer.

Less than 24 hours later, those valve issues were apparently solved as Starhopper’s Raptor ignited for the first time in a spectacular nighttime fireball. 48 hours after that first ignition, SpaceX once again fueled Starhopper and ignited its Raptor engine, lifting a spectacular handful of feet into the air before reaching the end of its very short tethers. According to Musk, the first Raptor ignition was completed with “all systems green”. After the second test, no additional comments were made. Less than three days later, SpaceX technicians uninstalled Starhopper’s Raptor (SN02) and shipped it somewhere offsite, indicating that it may have suffered a fault similar to the one that caused relatively minor damage to Raptor SN01 at the end of its February test campaign. Regardless, it appears that this development will keep Starhopper grounded for the indefinite future barring the imminent shipment of Raptor SN04 or the completion of SN01’s refurbishment.

The Raptor pack grows

Starhopper’s unplanned grounding ties

While the exact strategy behind SpaceX’s Raptor and BFR propulsion development programs

Regardless, the somewhat buggy behavior exhibited by the integrated Raptor and Starhopper indicate the obvious: both are fairly immature hardware still in some form of development, be it the late (Raptor) or the very earliest stages (Starhopper). By performing even more testing and continuing to optimize and gain familiarity with the hardware at hand, the fairly predictable process of development will arrive at more or less finished products.

Starship’s first orbital prototype

Last but not least, work continues on what will hopefully become the first orbit-capable Starship prototype, built in full-scale out of sheets of stainless steel that are far thinner than the metal used to construct Starhopper. This, too, is a normal process of development – as progress is made, prototypes will gradually lose an emergency cushion of performance margins, a bit like a sculptor starting with a solid block of marble and whittling it down to a work of art. Starhopper is that marble block, with inelegant, rough angles and far more material bulk than truly necessary.

As seen above, the orbital prototype – just the second in a presumably unfinished series – is already dramatically more refined. Instead of the first facade-like nose cone built for Starhopper, Starship’s nose section is being built out of smoothly tapered stainless steel panels that appear identical to those used to assemble the rocket’s growing aeroshell and tankage. As of now, there are five publicly visible Starship sections in various forms of fabrication, followed by a half-dozen or so tank dome segments waiting to be welded together as finished bulkheads.

Intriguingly, the only quasi-public official render of SpaceX’s steel Starship features visible sections very similar to those seen on the orbital prototype’s welded hull. They aren’t all visible in the render, but those that are are a distinct match to the aspect ratio of the welded sections visible in South Texas.

Extrapolating from this observation, Starship, as rendered, is comprised of approximately 16 large cylinder sections and 4-8 tapered nose sections. Based on the real orbital prototype, each large section is 9m in diameter and ~2.5m tall. Assuming Starship is 55 meters (180 ft) tall, this would translate into 22 2.5m sections, a nearly perfect fit with what is shown in the official render. Back in South Texas, SpaceX has 6 tapered sections and 7 cylinder sections in work, meaning that they would reach around 32.5m (~105 ft) – about 60% of a Starship hull – if stacked today.

If we assume that SpaceX follows Falcon procedures to build the seven-Raptor thrust structure separately (~2 sections) and excludes most of the cargo bay (~2-3 sections) on the first orbit-capable Starship, those ~13 in-work sections could be just a tapered nose cone away from the prototype’s full aeroshell. Time will tell…

Check out Teslarati’s newsletters for prompt updates, on-the-ground perspectives, and unique glimpses of SpaceX’s rocket launch and recovery processes.

News

SpaceX launches Ax-4 mission to the ISS with international crew

The SpaceX Falcon 9 launched Axiom’s Ax-4 mission to ISS. Ax-4 crew will conduct 60+ science experiments during a 14-day stay on the ISS.

SpaceX launched the Falcon 9 rocket kickstarting Axiom Space’s Ax-4 mission to the International Space Station (ISS). Axiom’s Ax-4 mission is led by a historic international crew and lifted off from Kennedy Space Center’s Launch Complex 39A at 2:31 a.m. ET on June 25, 2025.

The Ax-4 crew is set to dock with the ISS around 7 a.m. ET on Thursday, June 26, 2025. Axiom Space, a Houston-based commercial space company, coordinated the mission with SpaceX for transportation and NASA for ISS access, with support from the European Space Agency and the astronauts’ governments.

The Ax-4 mission marks a milestone in global space collaboration. The Ax-4 crew, commanded by U.S. astronaut Peggy Whitson, includes Shubhanshu Shukla from India as the pilot, alongside mission specialists Sławosz Uznański-Wiśniewski from Poland and Tibor Kapu from Hungary.

“The trip marks the return to human spaceflight for those countries — their first government-sponsored flights in more than 40 years,” Axiom noted.

Shukla’s participation aligns with India’s Gaganyaan program planned for 2027. He is the first Indian astronaut to visit the ISS since Rakesh Sharma in 1984.

Axiom’s Ax-4 mission marks SpaceX’s 18th human spaceflight. The mission employs a Crew Dragon capsule atop a Falcon 9 rocket, designed with a launch escape system and “two-fault tolerant” for enhanced safety. The Axiom mission faced a few delays due to weather, a Falcon 9 leak, and an ISS Zvezda module leak investigation by NASA and Roscosmos before the recent successful launch.

As the crew prepares to execute its scientific objectives, SpaceX’s Ax-4 mission paves the way for a new era of inclusive space research, inspiring future generations and solidifying collaborative ties in the cosmos. During the Ax-4 crew’s 14-day stay in the ISS, the astronauts will conduct nearly 60 experiments.

“We’ll be conducting research that spans biology, material, and physical sciences as well as technology demonstrations,” said Whitson. “We’ll also be engaging with students around the world, sharing our experience and inspiring the next generation of explorers.”

SpaceX’s Ax-4 mission highlights Axiom’s role in advancing commercial spaceflight and fostering international partnerships. The mission strengthens global space exploration efforts by enabling historic spaceflight returns for India, Poland, and Hungary.

News

Starlink Cellular’s T-Mobile service to grow with third-party app data

From Oct 2025, T-Satellite will enable third-party apps in dead zones! WhatsApp, X, AccuWeather + more coming soon.

Starlink Cellular’s T-Mobile service will expand with third-party app data support starting in October, enhancing connectivity in cellular dead zones.

T-Mobile’s T-Satellite, supported by Starlink, launches officially on July 23. Following its launch, T-Mobile’s Starlink Cellular service will enable data access for third-party apps like WhatsApp, X, Google, Apple, AccuWeather, and AllTrails on October 1, 2025.

T-Mobile’s Starlink Cellular is currently in free beta. T-Satellite will add MMS support for Android phones on July 23, with iPhone support to follow. MMS support allows users to send images and audio clips alongside texts. By October, T-Mobile will extend emergency texting to all mobile users with compatible phones, beyond just T-Mobile customers, building on its existing 911 texting capability. The carrier also provides developer tools to help app makers integrate their software with T-Satellite’s data service, with plans to grow the supported app list.

T-Mobile announced these updates during an event celebrating an Ookla award naming it the best U.S. phone network, a remarkable turnaround from its last-place ranking a decade ago.

“We not only dream about going from worst to best, we actually do it. We’re a good two years ahead of Verizon and AT&T, and I believe that lead is going to grow,” said T-Mobile’s Chief Operating Officer Srini Gopalan.

T-Mobile unveiled two promotions for its Starlink Cellular services to attract new subscribers. A free DoorDash DashPass membership, valued at $10/month, will be included with popular plans like Experience Beyond and Experience More, offering reduced delivery and service fees. Meanwhile, the Easy Upgrade promotion targets Verizon customers by paying off their phone balances and providing flagship devices like the iPhone 16, Galaxy S25, or Pixel 9.

T-Mobile’s collaboration with SpaceX’s Starlink Cellular leverages orbiting satellites to deliver connectivity where traditional networks fail, particularly in remote areas. Supporting third-party apps underscores T-Mobile’s commitment to enhancing user experiences through innovative partnerships. As T-Satellite’s capabilities grow, including broader app integration and emergency access, T-Mobile is poised to strengthen its lead in the U.S. wireless market.

By combining Starlink’s satellite technology with strategic promotions, T-Mobile is redefining mobile connectivity. The upcoming third-party app data support and official T-Satellite launch mark a significant step toward seamless communication, positioning T-Mobile as a trailblazer in next-generation wireless services.

News

Starlink expansion into Vietnam targets the healthcare sector

Starlink aims to deliver reliable internet to Vietnam’s remote clinics, enabling telehealth and data sharing.

SpaceX’s Starlink expansion into Vietnam targets its healthcare sector. Through Starlink, SpaceX seeks to drive digital transformation in Vietnam.

On June 18, a SpaceX delegation met with Vietnam’s Ministry of Health (MoH) in Hanoi. SpaceX’s delegation was led by Andrew Matlock, Director of Enterprise Sales, and the discussions focused on enhancing connectivity for hospitals and clinics in Vietnam’s remote areas.

Deputy Minister of Health (MoH) Tran Van Thuan emphasized collaboration between SpaceX and Vietnam. Tran stated: “SpaceX should cooperate with the MoH to ensure all hospitals and clinics in remote areas are connected to the StarLink satellite system and share information, plans, and the issues discussed by members of the MoH. The ministry is also ready to provide information and send staff to work with the corporation.”

The MoH assigned its Department of Science, Technology, and Training to work with SpaceX. Starlink Vietnam will also receive support from Vietnam’s Department of International Cooperation. Starlink Vietnam’s agenda includes improving internet connectivity for remote healthcare facilities, developing digital infrastructure for health examinations and remote consultations, and enhancing operational systems.

Vietnam’s health sector is prioritizing IT and digital transformation, focusing on electronic health records, data centers, and remote medical services. However, challenges persist in deploying IT solutions in remote regions, prompting Vietnam to seek partnerships like SpaceX’s.

SpaceX’s Starlink has a proven track record in healthcare. In Rwanda, its services supported 40 health centers, earning praise for improving operations. Similarly, Starlink enabled remote consultations at the UAE’s Emirati field hospital in Gaza, streamlining communication for complex medical cases. These successes highlight Starlink’s potential to transform Vietnam’s healthcare landscape.

On May 20, SpaceX met with Vietnam’s Ministry of Industry and Trade, announcing a $1.5 billion investment to provide broadband internet, particularly in remote, border, and island areas. The first phase includes building 10-15 ground stations across the country. This infrastructure will support Starlink’s healthcare initiatives by ensuring reliable connectivity.

Starlink’s expansion in Vietnam aligns with the country’s push for digital transformation, as outlined by the MoH. By leveraging its satellite internet expertise, SpaceX aims to bridge connectivity gaps, enabling advanced healthcare services in underserved regions. This collaboration could redefine Vietnam’s healthcare infrastructure, positioning Starlink as a key player in the nation’s digital future.

-

Elon Musk1 week ago

Elon Musk1 week agoTesla investors will be shocked by Jim Cramer’s latest assessment

-

Elon Musk3 days ago

Elon Musk3 days agoElon Musk confirms Grok 4 launch on July 9 with livestream event

-

Elon Musk13 hours ago

Elon Musk13 hours agoxAI launches Grok 4 with new $300/month SuperGrok Heavy subscription

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoTesla Model 3 ranks as the safest new car in Europe for 2025, per Euro NCAP tests

-

Elon Musk2 weeks ago

Elon Musk2 weeks agoA Tesla just delivered itself to a customer autonomously, Elon Musk confirms

-

Elon Musk1 week ago

Elon Musk1 week agoxAI’s Memphis data center receives air permit despite community criticism

-

Elon Musk2 weeks ago

Elon Musk2 weeks agoTesla’s Omead Afshar, known as Elon Musk’s right-hand man, leaves company: reports

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoXiaomi CEO congratulates Tesla on first FSD delivery: “We have to continue learning!”