News

SpaceX CEO Elon Musk shows off Starship’s 3 Raptor engines in best photos yet

SpaceX CEO Elon Musk has taken to Twitter to publish yet more photos of the company’s Starship Mk1 rocket prototype, this time posting what are – by far – the best official photos of Raptor engines yet taken.

This marks the first time that a SpaceX prototype of any kind has had more than one Raptor engine installed, a fairly symbolic but still significant milestone that follows in the footsteps of Starhopper’s successful single-engine flight test campaign. With Starhopper now heading into retirement, Starship Mk1 is preparing to support the program’s next major steps: full-scale, high-altitude flight tests powered by three Raptor engines.

The sight of three Raptor engines installed on the first true Starship prototype is undeniably hard to downplay. In barely seven months, SpaceX has gone from the very first static fire of a full-scale Raptor engine – serial number 01 – to flight-testing Raptor SN06 and producing enough engines to bestow Starship Mk1 with its own set of three engines. According to the latest comments from Elon Musk, Starship is meant to be powered by three ‘sea level’ Raptors and three vacuum-optimized Raptors – RVacs. RVac may or may not be ready to support the flight tests of early prototypes like Mk1 and Mk2, meaning that their three SL engines will likely be the sole propulsion for the time being.

Together, three SL Raptors operating at full thrust should be capable of producing up to 600 tons (1.3M lbf) of thrust. Per Musk’s note that Starship Mk1 likely weighs around 200 tons (~450,000 lb) empty, this means that a triple-engined Starship will be able to lift off with up to 400 tons (900,000 lb) of propellant, likely translating into roughly 200-300 seconds of untethered triple-engine operation.

“NOT FOR FLIGHT”

However, the engine installation milestone and subsequent photos are undeniably spectacular, but signs suggest that some level of pragmatism is in order. Visible in two of the three photos published by Musk, all three Raptors still have their transport rings installed just below each engine’s throat. Hardware at the base of one photo indicates that they were likely taken yesterday, on the evening of September 25th. Musk revealed that the three Raptors were installed late on September 22nd, up to three days prior.

Combined, the presence of the transport rings – “NOT FOR FLIGHT”, as their labels note – is a strong indicator that their installation is only temporary, likely in support of Elon Musk’s imminent September 28th Starship presentation. Without more information, it’s impossible to read much further into the temporary installation of Raptors. What it does confirm is that – for any number of reasons – flight-ready Raptors are not quite ready to support the Starship Mk1/Mk2. SpaceX has proven that Raptor is capable of supporting Starhopper for almost a full minute of powered flight, but behaviors observed near the end of that flight suggest that even that may have been pushing the engine’s limits.

All things considered, SpaceX is making progress at an almost unfathomable pace. Just seven months into full-scale Raptor test fires, it’s easy to believe that a lot of development work and refinement remains before the new engine family will be ready to reliably support multi-minute flight tests, let alone orbital launch attempts. Most orbital-class engine development programs aim for tens or even hundreds of thousands of seconds of test fires before attempting their first flights, but SpaceX is not most companies and is sticking closely to its preferred “test as you fly” methods and agile development strategies.

Check out Teslarati’s Marketplace! We offer Tesla accessories, including for the Tesla Cybertruck and Tesla Model 3.

News

Tesla debuts hands-free Grok AI with update 2025.26: What you need to know

All new Tesla vehicles delivered on or after July 12, 2025, will include Grok AI out of the box

Tesla has begun rolling out Grok, an in-car conversational AI assistant developed by xAI, to eligible vehicles starting July 12. The feature marks the most direct integration yet between Elon Musk’s artificial intelligence startup and Tesla’s consumer product lineup, offering drivers hands-free access to a chat-style companion while on the road.

Grok comes pre-installed on new vehicles

According to Tesla’s FAQ page for the feature, all new vehicles delivered on or after July 12, 2025, will include Grok AI out of the box. Owners of older vehicles may gain access through an over-the-air update, provided their vehicle meets a few hardware and software requirements.

Specifically, Grok is currently only supported on Tesla models equipped with an AMD infotainment processor and running vehicle software version 2025.26 and higher. Compatible models include the Model S, Model 3, Model X, Model Y, and Cybertruck. A Premium Connectivity subscription or active Wi-Fi connection is also required.

Tesla notes that additional vehicle compatibility may arrive in future software updates.

Grok’s features and limitations for now

Drivers can engage with Grok using the App Launcher or by pressing and holding the voice command button on the steering wheel. Grok is designed to answer questions and hold conversations using natural language, offering responses tailored to its chosen personality—ranging from “Storyteller” to the more eccentric “Unhinged.”

For fun, Tesla posted a demonstration of Grok likely running on “Unhinged” talking about what it would do to Optimus when they are on a date, much to the shock of the humanoid robot’s official social media account.

It should be noted, however, that Grok cannot currently issue commands to the vehicle itself, at least for now. Traditional voice commands for tasks like climate control, navigation, or media remain separate from Grok as of writing.

The feature is being released in Beta and does not require a Grok account or xAI subscription to activate, although that policy may change over time.

Grok privacy and in-car experience

Tesla emphasizes that interactions with Grok are securely processed by xAI and not linked to a user’s Tesla account or vehicle. Conversations remain anonymous unless a user signs into Grok separately to sync their history across devices.

Tesla has also begun promoting Grok directly on its official vehicle webpages, showcasing the feature as part of its in-car experience, further highlighting the company’s increasing focus on AI and infotainment features on its all-electric vehicles.

News

Tesla cleared in Canada EV rebate investigation

Tesla has been cleared in an investigation into the company’s staggering number of EV rebate claims in Canada in January.

Canadian officials have cleared Tesla following an investigation into a large number of claims submitted to the country’s electric vehicle (EV) rebates earlier this year.

Transport Canada has ruled that there was no evidence of fraud after Tesla submitted 8,653 EV rebate claims for the country’s Incentives for Zero-Emission Vehicles (iZEV) program, as detailed in a report on Friday from The Globe and Mail. Despite the huge number of claims, Canadian authorities have found that the figure represented vehicles that had been delivered prior to the submission deadline for the program.

According to Transport Minister Chrystia Freeland, the claims “were determined to legitimately represent cars sold before January 12,” which was the final day for OEMs to submit these claims before the government suspended the program.

Upon initial reporting of the Tesla claims submitted in January, it was estimated that they were valued at around $43 million. In March, Freeland and Transport Canada opened the investigation into Tesla, noting that they would be freezing the rebate payments until the claims were found to be valid.

READ MORE ON ELECTRIC VEHICLES: EVs getting cleaner more quickly than expected in Europe: study

Huw Williams, Canadian Automobile Dealers Association Public Affairs Director, accepted the results of the investigation, while also questioning how Tesla knew to submit the claims that weekend, just before the program ran out.

“I think there’s a larger question as to how Tesla knew to run those through on that weekend,” Williams said. “It doesn’t appear to me that we have an investigation into any communication between Transport Canada and Tesla, between officials who may have shared information inappropriately.”

Tesla sales have been down in Canada for the first half of this year, amidst turmoil between the country and the Trump administration’s tariffs. Although Elon Musk has since stepped back from his role with the administration, a number of companies and officials in Canada were calling for a boycott of Tesla’s vehicles earlier this year, due in part to his association with Trump.

News

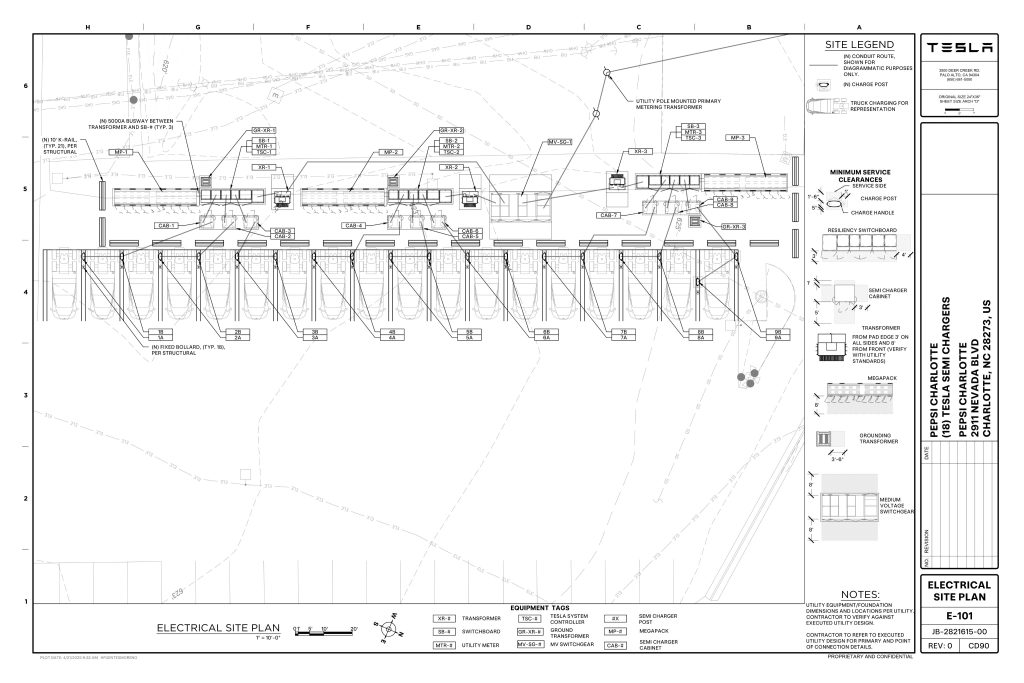

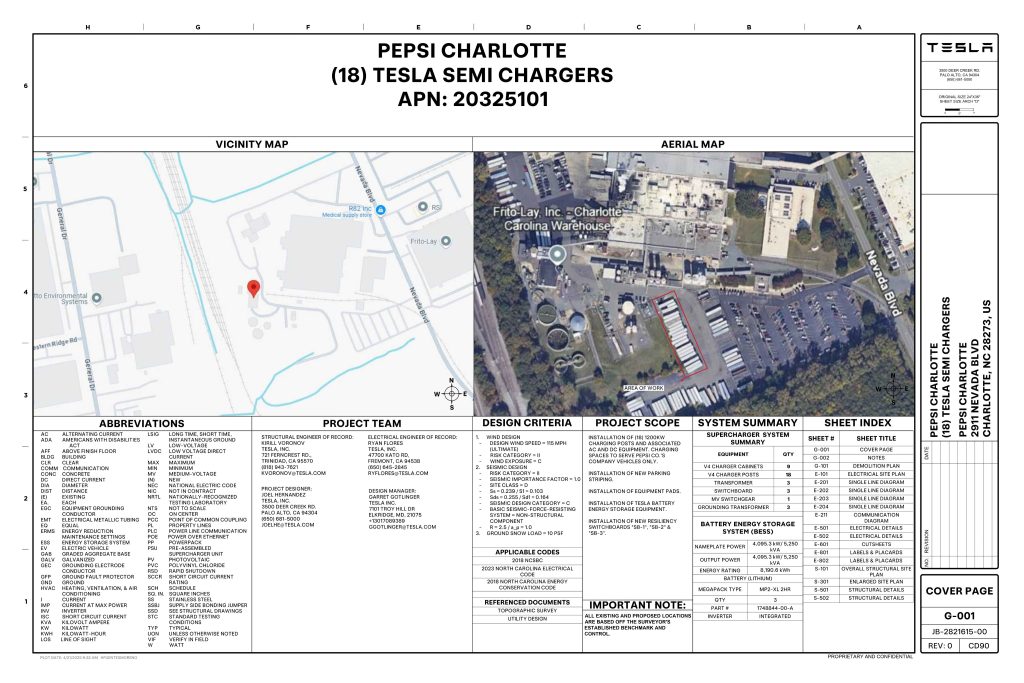

Tesla Semis to get 18 new Megachargers at this PepsiCo plant

PepsiCo is set to add more Tesla Semi Megachargers, this time at a facility in North Carolina.

Tesla partner PepsiCo is set to build new Semi charging stations at one of its manufacturing sites, as revealed in new permitting plans shared this week.

On Friday, Tesla charging station scout MarcoRP shared plans on X for 18 Semi Megacharging stalls at PepsiCo’s facility in Charlotte, North Carolina, coming as the latest update plans for the company’s increasingly electrified fleet. The stalls are set to be built side by side, along with three Tesla Megapack grid-scale battery systems.

The plans also note the faster charging speeds for the chargers, which can charge the Class 8 Semi at speeds of up to 1MW. Tesla says that the speed can charge the Semi back to roughly 70 percent in around 30 minutes.

You can see the site plans for the PepsiCo North Carolina Megacharger below.

Credit: PepsiCo (via MarcoRPi1 on X)

Credit: PepsiCo (via MarcoRPi1 on X)

READ MORE ON THE TESLA SEMI: Tesla to build Semi Megacharger station in Southern California

PepsiCo’s Tesla Semi fleet, other Megachargers, and initial tests and deliveries

PepsiCo was the first external customer to take delivery of Tesla’s Semis back in 2023, starting with just an initial order of 15. Since then, the company has continued to expand the fleet, recently taking delivery of an additional 50 units in California. The PepsiCo fleet was up to around 86 units as of last year, according to statements from Semi Senior Manager Dan Priestley.

Additionally, the company has similar Megachargers at its facilities in Modesto, Sacramento, and Fresno, California, and Tesla also submitted plans for approval to build 12 new Megacharging stalls in Los Angeles County.

Over the past couple of years, Tesla has also been delivering the electric Class 8 units to a number of other companies for pilot programs, and Priestley shared some results from PepsiCo’s initial Semi tests last year. Notably, the executive spoke with a handful of PepsiCo workers who said they really liked the Semi and wouldn’t plan on going back to diesel trucks.

The company is also nearing completion of a higher-volume Semi plant at its Gigafactory in Nevada, which is expected to eventually have an annual production capacity of 50,000 Semi units.

Tesla executive teases plan to further electrify supply chain

-

Elon Musk2 weeks ago

Elon Musk2 weeks agoTesla investors will be shocked by Jim Cramer’s latest assessment

-

Elon Musk2 days ago

Elon Musk2 days agoxAI launches Grok 4 with new $300/month SuperGrok Heavy subscription

-

Elon Musk5 days ago

Elon Musk5 days agoElon Musk confirms Grok 4 launch on July 9 with livestream event

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoTesla Model 3 ranks as the safest new car in Europe for 2025, per Euro NCAP tests

-

Elon Musk2 weeks ago

Elon Musk2 weeks agoA Tesla just delivered itself to a customer autonomously, Elon Musk confirms

-

Elon Musk1 week ago

Elon Musk1 week agoxAI’s Memphis data center receives air permit despite community criticism

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoXiaomi CEO congratulates Tesla on first FSD delivery: “We have to continue learning!”

-

Elon Musk2 weeks ago

Elon Musk2 weeks agoTesla scrambles after Musk sidekick exit, CEO takes over sales