Firmware

How Tesla brought a systems approach to the automobile

Everyone understands by now that Tesla does things differently than other automakers. However, most of the media attention centers on the vehicles’ performance (especially their 0-60 times), the marketing coup that the company performed in transforming electric cars from nerdy to cool, or the way Tesla has sidestepped the unloved auto dealers by selling directly to customers.

There’s another extremely important innovation that most non-Tesla owners aren’t aware of: Tesla’s vehicles are the first to use a single integrated computer system to control all of their functions, from battery charging to motor control to tuning the radio. Tesla co-founder Ian Wright made some insightful comments about this when I interviewed him for my book, Tesla: How Elon Musk and Company Made Electric Cars Cool, and Remade the Automotive and Energy Industries (edition 3.0, totally revised and updated in 2017, is now available). The following is adapted from the book.

|

Above: Recently revised and updated book, Tesla: How Elon Musk and Company Made Electric Cars Cool, and Remade the Automotive and Energy Industries, edition 3.0 (Source: Charles Morris)

Ian Wright, a native of New Zealand, is a racing enthusiast who converted a lawn mower to a go-kart at age 10. He moved to California in 1993, and happened to be a neighbor of Martin Eberhard, who was working with his long-time collaborator Marc Tarpenning to establish Tesla. Wright’s automotive expertise was just what Eberhard and Tarpenning needed, so he took the chance to combine his interests in software, engineering and racing, and became Tesla’s VP of Vehicle Development.

When I asked Ian Wright how Tesla had changed the way cars are developed and manufactured, he said that the company had indeed done so, but not in the ways that people might think. “The way that Toyota manufactures a car, the way they stamp the metal and weld them together and paint them and do all the interior bits and put the car together, it’s kind of hard to beat that,” said Wright. “I’m not sure that Tesla’s made any advances on that, or even gotten to the level of doing that. On the other hand, if you’re a Silicon Valley technology engineer, and you look at the way modern cars are designed from an electronics point of view, to use an Australian expression, it looks like a dog’s breakfast. It doesn’t appear that they have what we would call a systems architecture.”

People often describe the modern automobile as a “computer on wheels,” but it’s really more like a couple dozen small computers, not one. Unlike a computer network or a software application, a (non-Tesla) car is not designed as a single system – it’s a mishmash of separate, incompatible computer systems, each one sourced from a different supplier. As Ian Wright told me, “I’m looking out the window at my 2008 Volkswagen Touareg, and I bet that’s got sixty or seventy electronic black boxes, three hundred pounds of wiring harness, and software from twenty different companies in it. The major reliability problem with those cars is the electronics and software. I think Tesla did take a real Silicon Valley systems architecture perspective in designing all the electronics in the Model S. I don’t know to what extent that way of doing things will translate to the big guys, but I think it is a very different way of doing it and I expect that their electronics and software will wind up being quite a bit more reliable than what we’re used to in cars.”

All the software that runs Model S (and X, and 3) is integrated as a single, logical system, which means, according to Wright, “fewer black boxes, a simpler wiring harness, more integrated software, fewer surprises when something goes wrong and other things don’t work properly, or something weird starts happening.”

|

Above: One of the original Tesla co-founders, Ian Wright (Image: Charged)

“My 2008 Volkswagen has got a nice color LCD right there in the middle of the instrument cluster and it drives me crazy, because there’s plenty of room to have lots of information on there, but they’ve divided it into a bunch of big fields. One of the fields gives you the outside air temperature – until the low fuel warning goes off. When your low fuel warning goes off, they overwrite the temperature with the low fuel warning icon and until you put more fuel in the car, you can no longer tell what the outside air temperature is. They could so easily have moved stuff around and put that somewhere else, but they couldn’t do that because the way they developed things, there was a specific crew that did that, a specific piece of code – it’s done this way. That’s the sort of thing that Tesla gets right in their sleep, and the big guys really struggle with.”

The more integrated approach also means that, as technology improves, things can be upgraded quickly and smoothly. Minor improvements that a smartphone maker might roll out in weeks can take months or years in today’s auto industry. Tesla has made several major upgrades to its vehicles remotely, without the owners having to do anything. Making similar changes to a traditional vehicle would require bringing it back to the dealer. As far as I know, no other automaker has ever issued an improvement or upgrade for an existing vehicle, except to fix a faulty component.

In an EV, electronics and software are the very heart of the vehicle, so as the majors begin to produce EVs in volume, they will eventually be forced to adopt a more systems-oriented approach (although this isn’t likely to happen as long as they are simply adapting gas-powered models by dropping in an electric powertrain). Furthermore, two other powerful trends are converging with electrification: automation and connectivity. Keeping up with these advances will absolutely require a software-centric conception. This will be no minor adjustment for the automakers – it will be a revolution in the way they design and build their products. To build the electrified, autonomous, hyperconnected automobile of the 21st century using the current system would be like building a smartphone that incorporates one chip and operating system for telephony, another for the internet, another for the camera, another for the music player, etc.

It’s not just a question of doing a better job designing the electronics and software – the problems are inherent in the structure of the industry. As Wright explained to me, even though the majors are improving their software systems, “they generally don’t develop any of that stuff themselves, they write a spec and they send it out to Tier 1 suppliers like TRW, Siemens and Bosch. If they’re still doing it that way I think they’re still going to have a problem.”

Ian Wright told me that in January, 2014. Almost four years later, it doesn’t seem that much has changed. Automakers are upgrading the user interfaces in their vehicles, but most of them still look and feel a decade or so behind the times, compared to the functionality consumers are used to from their smartphones and tablets. A number of OEMs are experimenting with over-the-air software updates – GM plans to launch a new electrical vehicle architecture capable of over-the-air updates “before 2020,” and Porsche says its upcoming EV, the Mission E, will offer over-the-air updates and software-locked options. So far however, these innovations seem to apply mainly to a vehicle’s infotainment system. There’s no sign that any of the legacy automakers yet envision a system like Tesla’s, which uses one computer platform to control all of a vehicle’s functions.

===

Note: Article originally published on evannex.com, by Charles Morris

Firmware

Tesla mobile app shows signs of upcoming FSD subscriptions

It appears that Tesla may be preparing to roll out some subscription-based services soon. Based on the observations of a Wales-based Model 3 owner who performed some reverse-engineering on the Tesla mobile app, it seems that the electric car maker has added a new “Subscribe” option beside the “Buy” option within the “Upgrades” tab, at least behind the scenes.

A screenshot of the new option was posted in the r/TeslaMotors subreddit, and while the Tesla owner in question, u/Callump01, admitted that the screenshot looks like something that could be easily fabricated, he did submit proof of his reverse-engineering to the community’s moderators. The moderators of the r/TeslaMotors subreddit confirmed the legitimacy of the Model 3 owner’s work, further suggesting that subscription options may indeed be coming to Tesla owners soon.

Did some reverse engineering on the app and Tesla looks to be preparing for subscriptions? from r/teslamotors

Tesla’s Full Self-Driving suite has been heavily speculated to be offered as a subscription option, similar to the company’s Premium Connectivity feature. And back in April, noted Tesla hacker @greentheonly stated that the company’s vehicles already had the source codes for a pay-as-you-go subscription model. The Tesla hacker suggested then that Tesla would likely release such a feature by the end of the year — something that Elon Musk also suggested in the first-quarter earnings call. “I think we will offer Full Self-Driving as a subscription service, but it will be probably towards the end of this year,” Musk stated.

While the signs for an upcoming FSD subscription option seem to be getting more and more prominent as the year approaches its final quarter, the details for such a feature are still quite slim. Pricing for FSD subscriptions, for example, have not been teased by Elon Musk yet, though he has stated on Twitter that purchasing the suite upfront would be more worth it in the long term. References to the feature in the vehicles’ source code, and now in the Tesla mobile app, also listed no references to pricing.

The idea of FSD subscriptions could prove quite popular among electric car owners, especially since it would allow budget-conscious customers to make the most out of the company’s driver-assist and self-driving systems without committing to the features’ full price. The current price of the Full Self-Driving suite is no joke, after all, being listed at $8,000 on top of a vehicle’s cost. By offering subscriptions to features like Navigate on Autopilot with automatic lane changes, owners could gain access to advanced functions only as they are needed.

Elon Musk, for his part, has explained that ultimately, he still believes that purchasing the Full Self-Driving suite outright provides the most value to customers, as it is an investment that would pay off in the future. “I should say, it will still make sense to buy FSD as an option as in our view, buying FSD is an investment in the future. And we are confident that it is an investment that will pay off to the consumer – to the benefit of the consumer.” Musk said.

Firmware

Tesla rolls out speed limit sign recognition and green traffic light alert in new update

Tesla has started rolling out update 2020.36 this weekend, introducing a couple of notable new features for its vehicles. While there are only a few handful of vehicles that have reportedly received the update so far, 2020.36 makes it evident that the electric car maker has made some strides in its efforts to refine its driver-assist systems for inner-city driving.

Tesla is currently hard at work developing key features for its Full Self-Driving suite, which should allow vehicles to navigate through inner-city streets without driver input. Tesla’s FSD suite is still a work in progress, though the company has released the initial iterations of key features such Traffic Light and Stop Sign Control, which was introduced last April. Similar to the first release of Navigate on Autopilot, however, the capabilities of Traffic Light and Stop Sign Control were pretty basic during their initial rollout.

2020.36 Showing Speed Limit Signs in Visualization from r/teslamotors

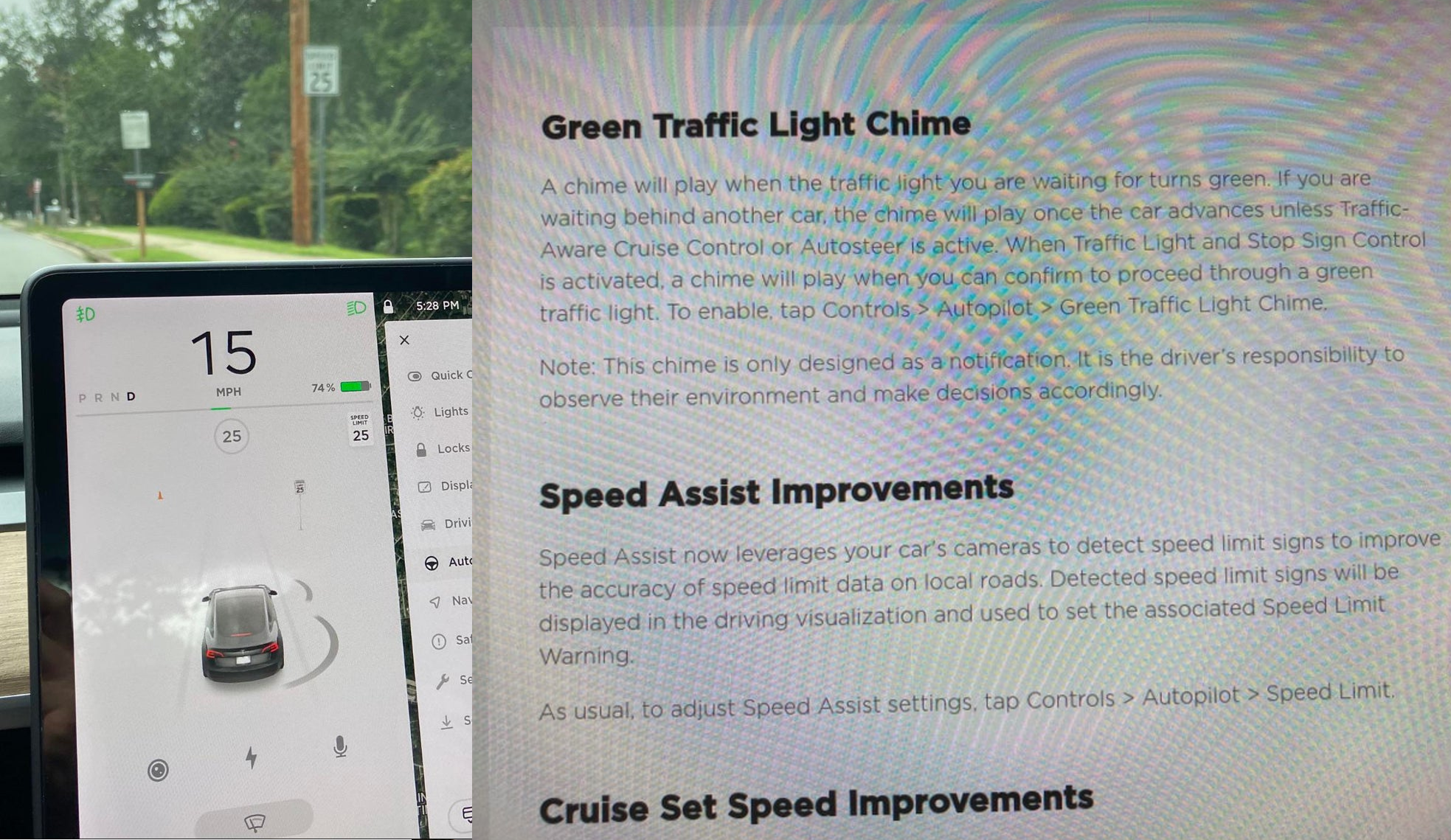

With the release of update 2020.36, Tesla has rolled out some improvements that should allow its vehicles to handle traffic lights better. What’s more, the update also includes a particularly useful feature that enables better recognition of speed limit signs, which should make Autopilot’s speed adjustments better during use. Following are the Release Notes for these two new features.

Green Traffic Light Chime

“A chime will play when the traffic light you are waiting for turns green. If you are waiting behind another car, the chime will play once the car advances unless Traffic-Aware Cruise Control or Autosteer is active. When Traffic Light and Stop Sign Control is activated, a chime will play when you can confirm to proceed through a green traffic light. To enable, tap Controls > Autopilot > Green Traffic Light Chime.

“Note: This chime is only designed as a notification. It is the driver’s responsibility to observe their environment and make decisions accordingly.”

Speed Assist Improvements

“Speed Assist now leverages your car’s cameras to detect speed limit signs to improve the accuracy of speed limit data on local roads. Detected speed limit signs will be displayed in the driving visualization and used to set the associated Speed Limit Warning.

“As usual, to adjust Speed Assist settings, tap Controls > Autopilot > Speed Limit.”

Footage of the new green light chime in action via @NASA8500 on Twitter ✈️ from r/teslamotors

Amidst the rollout of 2020.36’s new features, speculations were abounding among Tesla community members that this update may include the first pieces of the company’s highly-anticipated Autopilot rewrite. Inasmuch as the idea is exciting, however, Tesla CEO Elon Musk has stated that this was not the case. While responding to a Tesla owner who asked if the Autopilot rewrite is in “shadow mode” in 2020.36, Musk responded “Not yet.”

Firmware

Tesla rolls out Sirius XM free three-month subscription

Tesla has rolled out a free three-month trial subscription to Sirius XM, in what appears to be the company’s latest push into making its vehicles’ entertainment systems more feature-rich. The new Sirius XM offer will likely be appreciated by owners of the company’s vehicles, especially considering that the service is among the most popular satellite radios in the country today.

Tesla announced its new offer in an email sent on Monday. An image that accompanied the communication also teased Tesla’s updated and optimized Sirius XM UI for its vehicles. Following is the email’s text.

“Beginning now, enjoy a free, All Access three-month trial subscription to Sirius XM, plus a completely new look and improved functionality. Our latest over-the-air software update includes significant improvements to overall Sirius XM navigation, organization, and search features, including access to more than 150 satellite channels.

“To access simply tap the Sirius XM app from the ‘Music’ section of your in-car center touchscreen—or enjoy your subscription online, on your phone, or at home on connected devices. If you can’t hear SiriusXM channels in your car, select the Sirius XM ‘Subscription’ tab for instruction on how to refresh your audio.”

Tesla has actually been working on Sirius XM improvements for some time now. Back in June, for example, Tesla rolled out its 2020.24.6.4 update, and it included some optimizations to its Model S and Model X’s Sirius XM interface. As noted by noted Tesla owner and hacker @greentheonly, the source code of this update revealed that the Sirius XM optimizations were also intended to be released to other areas such as Canada.

Interestingly enough, Sirius XM is a popular feature that has been exclusive to the Model S and X. Tesla’s most popular vehicle to date, the Model 3, is yet to receive the feature. One could only hope that Sirius XM integration to the Model 3 may eventually be included in the future. Such an update would most definitely be appreciated by the EV community, especially since some Model 3 owners have resorted to using their smartphones or third-party solutions to gain access to the satellite radio service.

The fact that Tesla seems to be pushing Sirius XM rather assertively to its customers seems to suggest that the company may be poised to roll out more entertainment-based apps in the coming months. Apps such as Sirius XM, Spotify, Netflix, and YouTube, may seem quite minor when compared to key functions like Autopilot, after all, but they do help round out the ownership experience of Tesla owners. In a way, Sirius XM does make sense for Tesla’s next-generation of vehicles, especially the Cybertruck and the Semi, both of which would likely be driven in areas that lack LTE connectivity.

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoTesla Robotaxi’s biggest challenge seems to be this one thing

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoTesla confirms massive hardware change for autonomy improvement

-

Elon Musk2 weeks ago

Elon Musk2 weeks agoElon Musk slams Bloomberg’s shocking xAI cash burn claims

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoTesla features used to flunk 16-year-old’s driver license test

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoTesla China roars back with highest vehicle registrations this Q2 so far

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoTexas lawmakers urge Tesla to delay Austin robotaxi launch to September

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoTesla dominates Cars.com’s Made in America Index with clean sweep

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoTesla’s Grok integration will be more realistic with this cool feature