Space

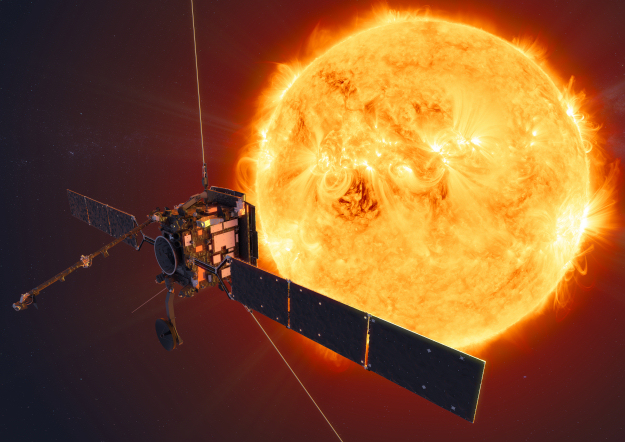

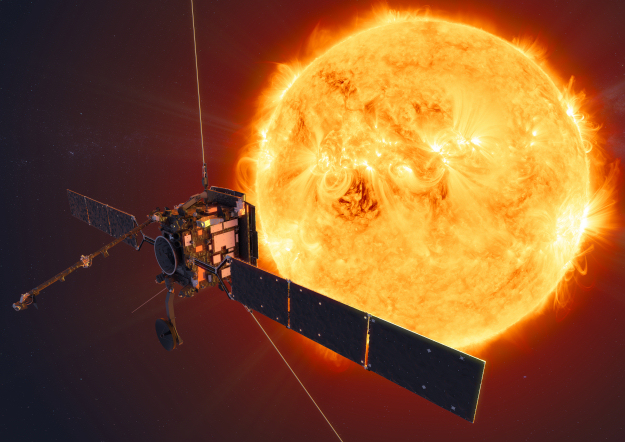

New Sun mission to launch in attempt to snap 1st-ever photos of star’s poles

A new spacecraft is set to launch on a journey to the Sun. It’s goal: to snap the first pictures of the Sun’s north and south poles.

Dubbed Solar Orbiter, the spacecraft is a collaboration between the European Space Agency (ESA) and NASA. The 3,970-lb. (1,320 kg) spacecraft will launch atop United Launch Alliance (ULA) Atlas V rocket on Feb. 7, 2020, during a two-hour launch window that opens at 11:15 p.m. EST (0415 GMT Feb. 8).

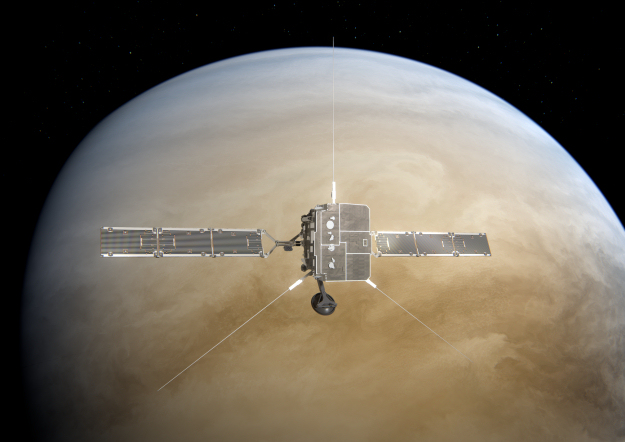

It’s launching at night because the spacecraft is on a path to Venus where it will use the planet’s gravity to slingshot itself out of the ecliptic plane — the area of space where all planets orbit.

From that vantage point, Solar Orbiter’s on-board cameras will capture the first-ever view of the Sun’s poles.

“Up until Solar Orbiter, all solar imaging instruments have been within the ecliptic plane or very close to it,” Russell Howard, space scientist at the Naval Research Lab in Washington, D.C. and principal investigator for one of Solar Orbiter’s ten instruments said in a mission update. “Now, we’ll be able to look down on the Sun from above.”

“It will be terra incognita,” added Daniel Müller, ESA project scientist for the mission at the European Space Research and Technology Centre in the Netherlands. “This is really exploratory science.”

The spacecraft is taking a suite of specialized instruments with it on its journey to the sun. It will also work in tandem with another solar-observing spacecraft—NASA’s Parker Solar Probe.

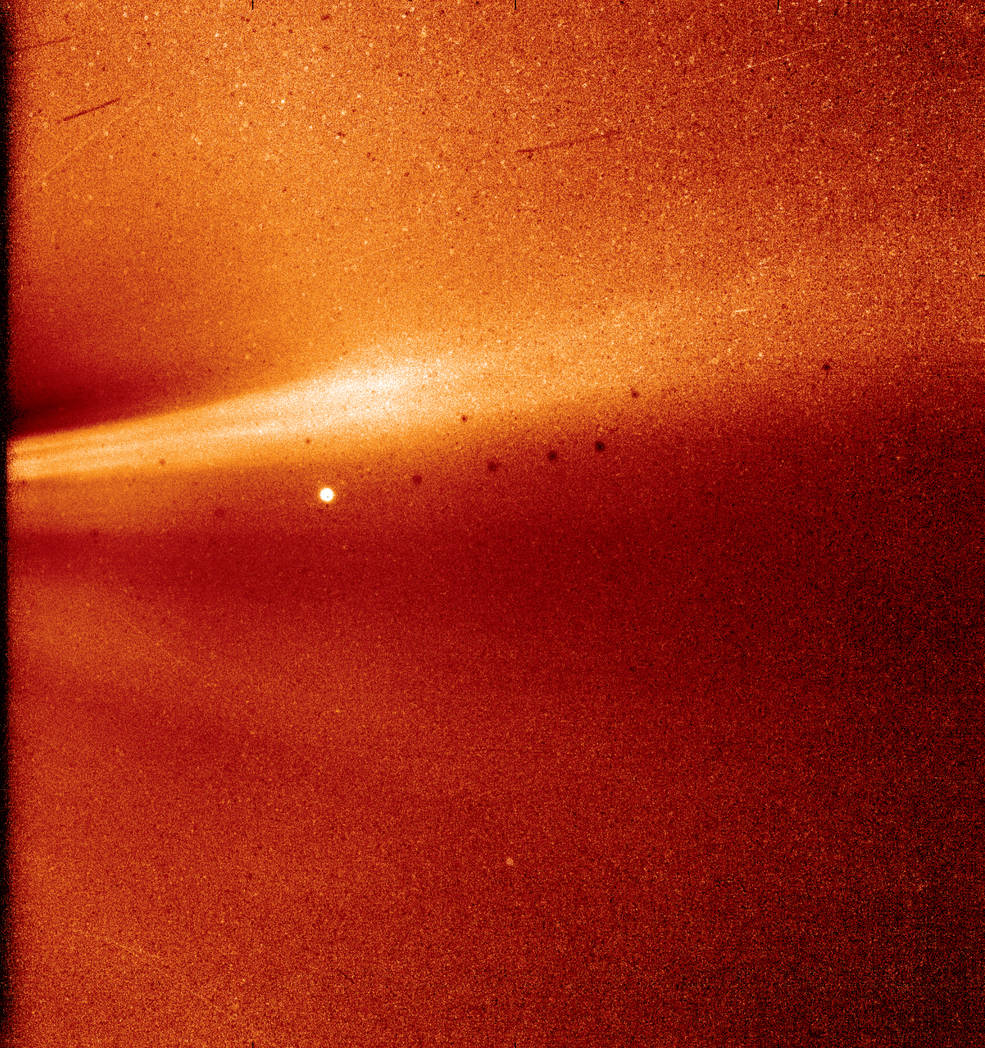

Launched in 2018, Parker has now completed its first few close passes of the sun. The spacecraft is already making discoveries, showing that despite appearance, the sun is anything but quiet.

It plays a central role in shaping space around us. As a magnetically active star, the sun unleashes powerful bursts of light and a slew of charged particles (racing at near light-speed) across the solar system. This violent activity has been happening throughout the sun’s 5.5 billion-year lifespan and affects our planet daily.

The sun has a massive magnetic field, which stretches far beyond Pluto, and creates the boundary between our solar system and interstellar space. It also creates a path for charged particles to whiz across the solar system.

The barrage of energetic particles, known as the solar wind, can damage spacecraft, satellites, and is harmful to our astronauts. It can disrupt navigation signals, and during extreme flares, can even trigger power outages.

But we can prepare for these things by monitoring the sun’s activity and magnetic field. However, our view from Earth is limited and leaves us with incomplete data. Scientists are hoping that by observing the sun’s polar regions, Solar Orbiter will be able to fill in the gaps in our knowledge.

“The poles are particularly important for us to be able to model more accurately,” Holly Gilbert, NASA project scientist for the mission at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “For forecasting space weather events, we need a pretty accurate model of the global magnetic field of the Sun.”

Solar Orbiter will take seven years to reach a viewpoint 24 degrees above the Sun’s equator, increasing to 33 degrees if the mission is extended an additional three years. That will provide the best views ever of the poles.

Additionally, the poles may be able to shed some light on the driving force behind sun spots — dark spots on the sun’s surface that mark strong magnetic fields. In 1843, German astronomer, Samuel Heinrich Schwabe, discovered that the spots increase and decrease during the solar cycle in a repeating pattern.

There are an abundance of sunspots during solar maximum (when the sun is active and turbulent) and fewer during solar minimum (when the sun is calmer). But scientists don’t understand why the cycle lasts 11 years, or why some solar maximums are stronger than others.

They hope to find the answer by observing the changing magnetic fields at the poles.

There’s only been one other spacecraft to fly over the sun’s polar regions: another joint ESA/NASA venture called Ulysses. It made three passes around the sun before being decommissioned in 2009. However, unlike Solar Orbiter, Ulysses did not have an imager on board to take pictures of the poles.

That spacecraft also did not get nearly as close as Solar Orbiter will. That’s because it lacked the technology required to keep it cool. Scientists have been waiting more than 60 years for missions like Parker Solar Probe and Solar Orbiter to come online.

It’s takes a lot of technology development to be able to design and build a spacecraft that will survive a close encounter with the sun.

Solar Orbiter is outfitted with a custom-designed titanium heat shield, topped with a calcium phosphate coating that withstands temperatures over 900 degrees Fahrenheit (482 degrees Celsius). That’s thirteen times the amount of heat that spacecraft in Earth-orbit are subjected to.

News

SpaceX Ax-4 Mission prepares for ISS with new launch date

SpaceX, Axiom Space, and NASA set new launch date for the Ax-4 mission after addressing ISS & rocket concerns.

SpaceX is preparing for a new launch date for the Ax-4 mission to the International Space Station (ISS).

SpaceX, Axiom Space, and NASA addressed recent technical challenges and announced a new launch date of no earlier than Thursday, June 19, for the Ax-4 mission. The delay from June 12 allowed teams to assess repairs to small leaks in the ISS’s Zvezda service module.

NASA and Roscosmos have been monitoring leaks in the Zvezda module’s aft (back) segment for years. However, stable pressure could also result from air flowing across the hatch seal from the central station. As NASA and its partners adapt launch schedules to ensure station safety, adjustments are routine.

“Following the most recent repair, pressure in the transfer tunnel has been stable,” a source noted, suggesting the leaks may be sealed.

“By changing pressure in the transfer tunnel and monitoring over time, teams are evaluating the condition of the transfer tunnel and the hatch seal between the space station and the back of Zvezda,” the source added.

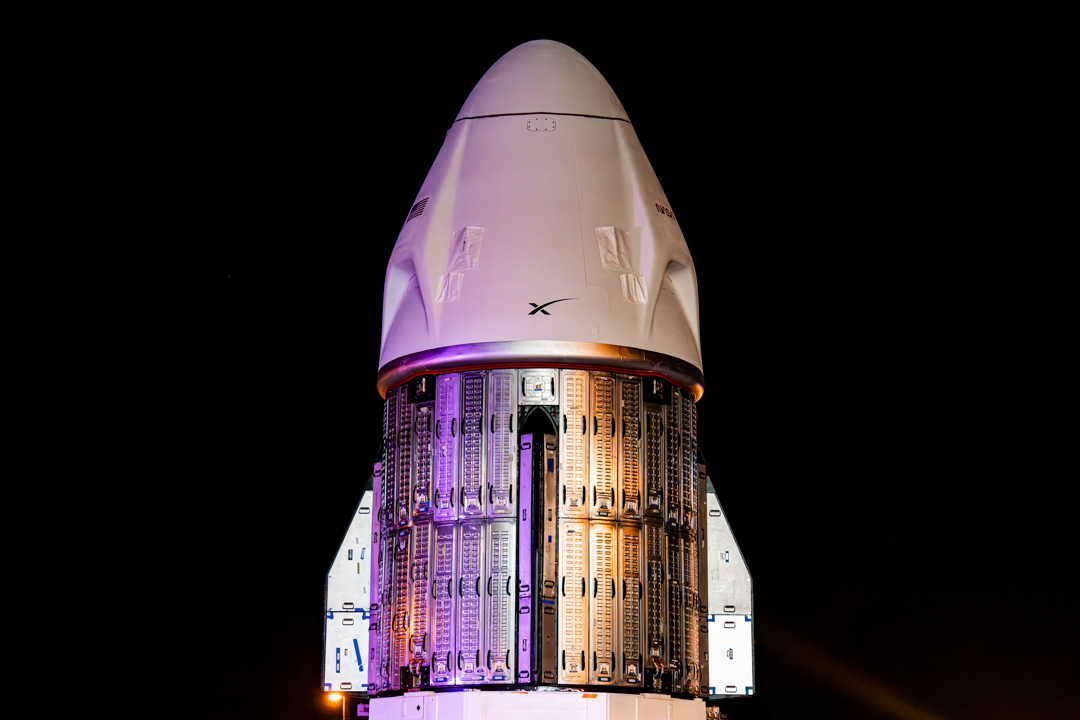

SpaceX has also resolved a liquid oxygen leak found during post-static fire inspections of the Falcon 9 rocket, completing a wet dress rehearsal to confirm readiness. The Ax-4 mission is Axiom Space’s fourth private astronaut trip to the ISS. It will launch from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on a Falcon 9 rocket with a new Crew Dragon capsule.

“This is the first flight for this Dragon capsule, and it’s carrying an international crew—a perfect debut. We’ve upgraded storage, propulsion components, and the seat lash design for improved reliability and reuse,” said William Gerstenmaier, SpaceX’s vice president of build and flight reliability.

The Ax-4 mission crew is led by Peggy Whitson, Axiom Space’s director of human spaceflight and former NASA astronaut. The Ax-4 crew includes ISRO astronaut Shubhanshu Shukla as pilot, alongside mission specialists Sławosz Uznański-Wiśniewski from Poland and Tibor Kapu from Hungary. The international team underscores Axiom’s commitment to global collaboration.

The Ax-4 mission will advance scientific research during its ISS stay, supporting Axiom’s goal of building a commercial space station. As teams finalize preparations, the mission’s updated launch date and technical resolutions position it to strengthen private space exploration’s role in advancing space-based innovation.

News

Starlink India launch gains traction with telecom license approval

Starlink just secured its telecom license in India! High-speed satellite internet could go live in 2 months.

Starlink India’s launch cleared a key regulatory hurdle after securing a long-awaited license from the country’s telecom ministry. Starlink’s license approval in India paves the way for commercial operations to begin, marking a significant milestone after a three-year wait.

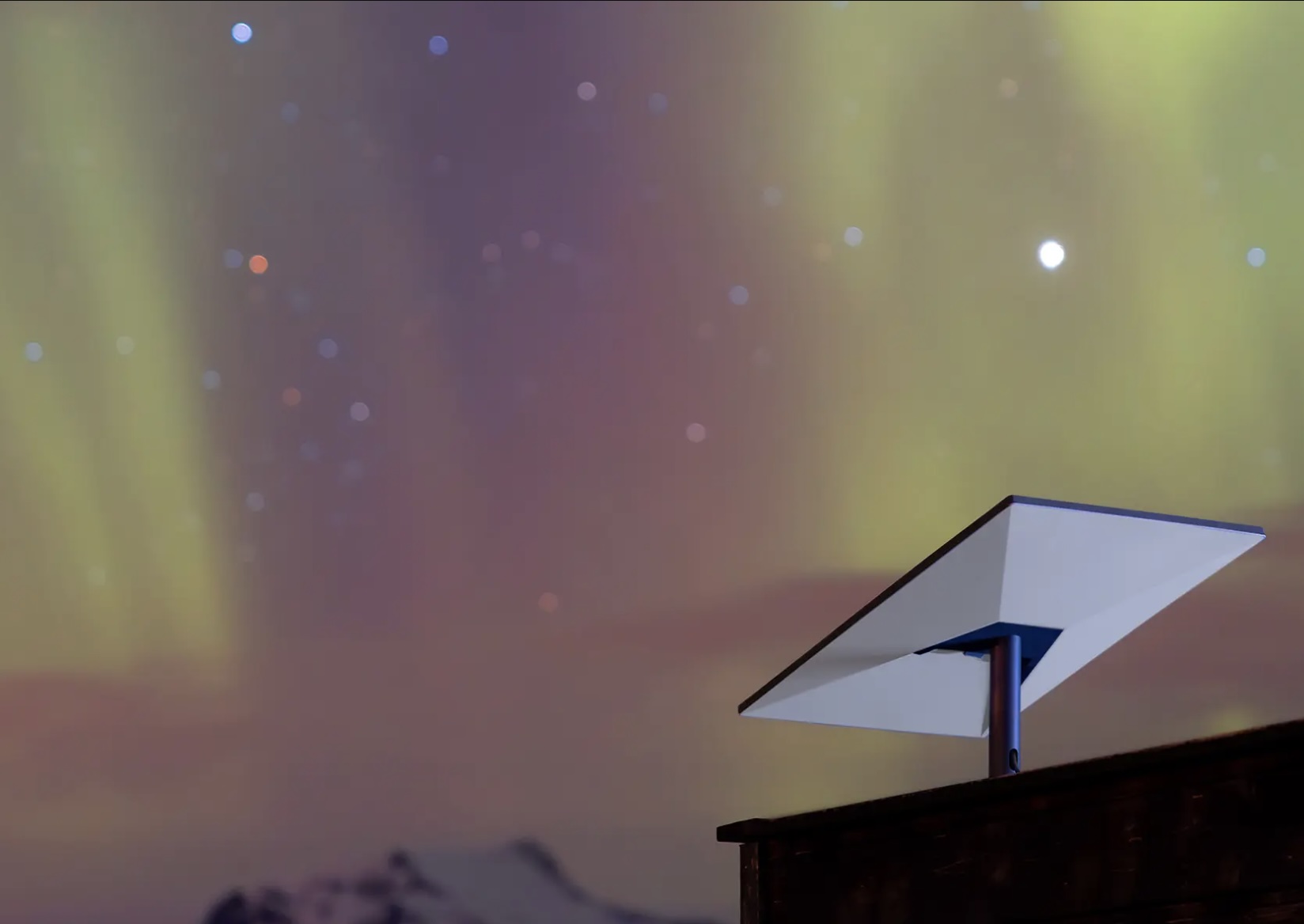

The Department of Telecommunications granted Starlink a Global Mobile Personal Communication by Satellite (GMPCS) license, enabling it to roll out its high-speed internet service. Local reports hinted that Starlink plans to launch its services within the next two months. Starlink India’s services are expected to be priced at ₹3,000 per month for unlimited data. Starlink service would require a ₹33,000 hardware kit, including a dish and router.

“Starlink is finally ready to enter the Indian market,” sources familiar with the rollout plans confirmed, noting a one-month free trial for new users.

Starlink’s low-Earth orbit satellite network promises low-latency, high-speed internet that is ideal for rural India, border areas, and hilly terrains. With over 7,000 satellites in orbit and millions of global users, Starlink aims to bridge India’s digital divide, especially in areas with limited traditional broadband.

Starlink has forged distribution partnerships with Indian telecom giants Reliance Jio and Bharti Airtel to streamline deployment and retail logistics. However, the company still awaits spectrum allocation and final clearances from India’s space regulator, IN-SPACe, and national security agencies before its full launch, expected before August 2025.

India’s satellite internet market is becoming increasingly competitive, with Starlink joining rivals like OneWeb and Jio Satellite Communications. While Starlink positions itself as a premium offering, its entry has sparked debate among domestic telecom operators over spectrum pricing.

Local reports noted that other players in the industry have raised concerns over the lower regulatory fees proposed for satellite firms compared to terrestrial operators, highlighting tensions in the sector.

Starlink India’s launch represents a transformative step toward expanding internet access in one of the world’s largest markets. Starlink could redefine connectivity for millions in underserved regions by leveraging its advanced satellite technology and strategic partnerships. As the company navigates remaining regulatory steps, its timely rollout could set a new standard for satellite internet in India, intensifying competition and driving innovation in the telecom landscape.

Elon Musk

SpaceX to decommission Dragon spacecraft in response to Pres. Trump war of words with Elon Musk

Elon Musk says SpaceX will decommission Dragon as a result of President Trump’s threat to end his subsidies and government contracts.

SpaceX will decommission its Dragon spacecraft in response to the intense war of words that President Trump and CEO Elon Musk have entered on various social media platforms today.

President Trump and Musk, who was once considered a right-hand man to Trump, have entered a vicious war of words on Thursday. The issues stem from Musk’s disagreement with the “Big Beautiful Bill,” which will increase the U.S. federal deficit, the Tesla and SpaceX frontman says.

How Tesla could benefit from the ‘Big Beautiful Bill’ that axes EV subsidies

The insults and threats have been brutal, as Trump has said he doesn’t know if he’ll respect Musk again, and Musk has even stated that the President would not have won the election in November if it were not for him.

President Trump then said later in the day that:

“The easiest way to save money in our Budget, Billions and Billions of Dollars, is to terminate Elon’s Government Subsidies and Contracts. I was always surprised that Biden didn’t do it!”

Musk’s response was simple: he will decommission the SpaceX capsule responsible for transporting crew and cargo to the International Space Station (ISS): Dragon.

🚨 Elon says Dragon will be decommissioned immediately due to President Trump’s threats to terminate SpaceX’s government contracts https://t.co/XNB0LflZIy

— TESLARATI (@Teslarati) June 5, 2025

Dragon has completed 51 missions, 46 of which have been to the ISS. It is capable of carrying up to 7 passengers to and from Earth’s orbit. It is the only spacecraft that is capable of returning vast amounts of cargo to Earth. It is also the first private spacecraft to take humans to the ISS.

The most notable mission Dragon completed is one of its most recent, as SpaceX brought NASA astronauts Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams back to Earth after being stranded at the ISS by a Boeing Starliner capsule.

SpaceX’s reluctance to participate in federally funded projects may put the government in a strange position. It will look to bring Boeing back in to take a majority of these projects, but there might be some reluctance based on the Starliner mishap with Wilmore and Williams.

SpaceX bails out Boeing and employees are reportedly ‘humiliated’

-

Elon Musk2 weeks ago

Elon Musk2 weeks agoTesla investors will be shocked by Jim Cramer’s latest assessment

-

Elon Musk2 days ago

Elon Musk2 days agoxAI launches Grok 4 with new $300/month SuperGrok Heavy subscription

-

Elon Musk4 days ago

Elon Musk4 days agoElon Musk confirms Grok 4 launch on July 9 with livestream event

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoTesla Model 3 ranks as the safest new car in Europe for 2025, per Euro NCAP tests

-

Elon Musk2 weeks ago

Elon Musk2 weeks agoA Tesla just delivered itself to a customer autonomously, Elon Musk confirms

-

Elon Musk1 week ago

Elon Musk1 week agoxAI’s Memphis data center receives air permit despite community criticism

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoXiaomi CEO congratulates Tesla on first FSD delivery: “We have to continue learning!”

-

Investor's Corner2 weeks ago

Investor's Corner2 weeks agoTesla gets $475 price target from Benchmark amid initial Robotaxi rollout